« 拉丁美洲冷战与古巴革命 » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

|||

| Ligne 45 : | Ligne 45 : | ||

== 冷战的影响(1947 年) == | == 冷战的影响(1947 年) == | ||

1947 年,拉丁美洲在第二次世界大战后经历了一定程度的开放,但这一态势因美国加入冷战而戛然而止。这一时期,美国在该地区的军事力量得到加强,对地区政策产生了重大影响。在冷战背景下,美国采取了坚决反苏的政策,并在其主导的美洲国家间会议上努力向其他美洲国家宣传这一政策。这一时期的主要成就之一是 1947 年签署了《里约条约》。该条约建立了美洲国家之间的互助体系,并宣布对其中一个国家的任何武装攻击或威胁都将被视为对所有美洲国家的攻击。里约条约》加强了美国作为拉丁美洲霸主的地位,并为该地区的军事合作建立了框架。这也是美国遏制苏联在拉美地区的影响、防止共产主义在该地区蔓延的战略的重要工具。然而,加入该条约并非没有争议,因为许多拉美国家担心这会导致该地区过度军事化,削弱其国家主权。这一时期地缘政治紧张,竞争激烈,美国在冷战期间在确定拉丁美洲政治议程方面发挥了核心作用。 | |||

大多数拉美国家签署的《里约条约》的主要目的是遏制冷战期间共产主义在该地区扩张的威胁。该条约为签署国之间的军事合作建立了框架,美国在向这些国家的武装部队提供军事援助和培训方面发挥了核心作用。该条约还为美国干预拉美国家事务以保护其所认为的安全利益提供了理由。实际上,《里约条约》创建了一个集体防御机制,签署该条约的美洲国家承诺在发生武装侵略或安全威胁时相互支持。如果其中一个国家受到攻击,其他成员国有义务向其提供援助,从而巩固了美国作为该地区霸主的地位,并保证其在反共斗争中的领导地位。因此,《里约条约》成为冷战期间美国在拉丁美洲推行遏制政策的基石。它使美国有理由在该地区进行军事和政治干预,以对抗共产主义的影响,而这往往会损害国家主权和民主原则。这一时期的特点是美国强势介入拉美国家的内部事务,对该地区的政治和稳定产生了重大影响。 | |||

美国加入冷战并加强其在拉丁美洲的军事力量,对该地区产生了深远而持久的影响。这一时期加剧了对民主体制的侵蚀,强化了独裁军事政权的盛行,并增加了对人权的侵犯。美国推行的冷战政策往往损害了拉丁美洲的民主价值观和公民自由。得到美国支持的专制政府得到了大量支持,这有助于他们继续掌权,尽管他们采取了镇压行动。这些政权系统地侵犯人权,镇压政治反对派,并对公民社会施加严格限制。在这种情况下,酷刑、法外处决和媒体审查等公然侵权行为屡见不鲜。美国的影响也经常阻碍举行自由公正的选举,破坏该地区的民主。拉丁美洲花了许多年才从这一政治动荡和镇压时期恢复过来。20 世纪 80 年代和 90 年代的民主过渡标志着一个重要的转折点,人们努力对过去的侵权行为进行问责、恢复民主和促进人权。然而,这一时期的后果却一直存在,在该地区的集体记忆中留下了深深的伤痕,并对拉丁美洲的政治和社会产生了持久的影响。 | |||

冷战期间,美国认为自己受到苏联和共产主义意识形态的攻击。在此背景下,美国政府认为拉丁美洲是一个容易受到共产主义影响的地区,并将共产主义在该地区的传播视为对其自身安全的威胁。因此,美国采取了各种手段,试图拉拢拉美国家支持其反共事业。美国向其认为有利于自身利益的政权提供军事和经济援助,同时积极推翻其认为是共产主义或同情共产主义的政府。他们还利用宣传来推广自己的世界观,将共产主义及其支持者妖魔化,并影响该地区的公众舆论。许多拉美国家感受到了在反冷战斗争中与美国结盟的压力,即使它们并不完全赞同美国的观点或利益。一些国家,如古巴和尼加拉瓜,明确反对美国的世界观,并采取了反美政策。然而,该地区大多数国家发现自己处于一个微妙的位置,既要努力维护自己的独立和主权,又要在反共斗争中与美国保持一致。这种态势对拉丁美洲产生了重大影响。它导致了民主体制的削弱、社会冲突和不平等的长期存在,以及美国支持的独裁政权的盛行。美国在反冷战斗争中拉拢拉美国家支持其事业的努力往往是以牺牲该地区的民主价值观和人权为代价的。拉美花了很多年才从这段政治动荡和镇压时期恢复过来,对该地区的政治、经济和社会造成了持久影响。20 世纪 80 年代和 90 年代的民主过渡标志着该地区历史上的一个重要里程碑,人们努力对过去的侵权行为做出解释,并建立更加尊重人权的更强大的民主制度。[[Image:Peter Stehlik.jpg|thumb|美洲国家组织总部设在华盛顿特区的泛美联盟大楼内。]] | |||

美洲国家组织(OAS)总部位于华盛顿特区的泛美联盟大厦。该大厦建成于 1910 年,是美洲国家组织的前身美洲共和国国际联盟的总部所在地。如今,这座标志性建筑是美洲国家组织的主要行政中心,也是世界上历史最悠久的区域组织。美洲国家组织成立于 1948 年,旨在促进美洲的民主、人权和经济发展。该组织汇集了来自北美洲、中美洲、南美洲和加勒比海地区的 35 个成员国。它在该地区成员国之间的合作和政策协调方面发挥着至关重要的作用,致力于保护人权、促进民主、解决冲突和社会经济发展等问题。美洲国家组织是众多旨在加强美洲政治稳定和尊重民主价值观的辩论和倡议的论坛。美洲国家组织总部设在华盛顿特区,体现了其作为促进美洲国家间合作与理解的重要地区组织的重要性。 | |||

美洲国家组织(OAS)成立于 1948 年,是一个旨在促进美洲国家间合作与团结的地区性组织。然而,虽然《美洲国家组织宪章》规定了不干涉和不干预原则,但现实情况是,美国经常主导该组织。在整个冷战期间,美国利用美洲国家组织作为促进其在该地区利益的工具,常常损害其他成员国的主权和独立。美洲国家组织于 1962 年通过了一项决议,宣布共产主义与民主不相容,这给美国和其他成员国提供了一个借口,可以干涉被认为同情共产主义的其他国家的内政。此外,由于美国在该地区的经济和军事实力,以及该组织总部设在华盛顿特区这一事实,美国在美洲国家组织内历来具有相当大的影响力。这常常导致有人指责美洲国家组织偏袒美国,并被用来促进美国在该地区的利益。尽管有这些批评,美洲国家组织还是促进了美洲的民主和人权,并在调解成员国之间的冲突方面发挥了关键作用。近年来,该组织一直在努力重申其独立性,并促进以更加平衡的方式处理地区问题。然而,美国主导美洲国家组织的历史仍是该地区的争议焦点。 | |||

20 世纪 60 年代,美国将拉丁美洲视为全球反共斗争的潜在战场。他们担心苏联在该地区扩张的可能性。这种观点受到多种因素的影响,尤其是 1959 年的古巴革命,这场革命在距离美国海岸仅 90 英里的地方建立了一个社会主义政府。1947 年的《里约条约》规定,任何对美洲成员国安全或领土完整的威胁都将被视为对所有成员国的威胁。这意味着,如果该地区的任何国家受到外来势力的攻击或威胁,美国将有义务保护该国。这被视为一种威慑来自地区外的侵略和促进地区团结以应对共同威胁的方式。然而,随着冷战的发展,美国开始对这一条款进行更宽泛的解释,认为对成员国安全的任何内部威胁,如共产主义的传播,也会威胁到美国。这种解释为美国干涉地区其他国家的内政提供了借口,而这些国家的主权或独立往往很少受到重视。在此背景下,美国越来越多地参与支持该地区的反共力量,特别是通过军事援助和培训、秘密行动和直接干预冲突。这导致了一系列有争议、有时甚至是血腥的干预行动,包括在危地马拉、尼加拉瓜和智利。 | |||

门罗主义由詹姆斯-门罗总统于1823年首次提出,宣称美国反对欧洲列强殖民或干涉西半球国家事务的任何企图。随着时间的推移,这一理论被解释为美国干预拉丁美洲的理由,特别是在冷战期间。在此期间,美国国会投票赞成向拉美国家提供军事援助,通常采取经济和军事援助计划的形式。这些援助旨在加强这些国家的军事能力,遏制苏联在该地区的影响。然而,这些资金的很大一部分被用于购买美国制造的武器和军事装备,从而刺激了美国国防工业的发展。美国的军事援助往往带有附加条件,因为美国试图在拉美地区促进自己的利益和价值观。这包括鼓励民主、人权以及反对左翼运动和政府。然而,在某些情况下,美国的军事援助被用来支持专制独裁政权,导致该地区国家出现侵犯人权和政治压迫的现象。 | |||

冷战期间,美国向拉美国家提供的军事援助具有重要意义。这种援助采取一揽子经济和军事援助的形式,旨在加强拉美国家抵御内部和外部威胁的防御能力。然而,这些援助中有相当一部分被指定用于购买美国制造的武器和军事装备,这有助于刺激美国国防工业的发展。这种做法也是美国通过加强地区盟国的军事能力来促进其利益和价值观的一种方式。这种态势在多个领域产生了重大影响。首先,它使美国成为全球军火贸易的主要参与者,为专门从事军火生产的美国公司创造了就业机会和收入。它还加强了拉美国家在军事和安全支持方面对美国的依赖,从而巩固了美国在该地区的影响力。然而,武器在该地区的扩散也助长了许多国家的内部冲突和不稳定,使冷战期间美国对拉美的军事援助产生了复杂而持久的后果。 | |||

除了美国的军事援助和武器销售,冷战期间美国还在拉丁美洲实施了各种培训计划和反叛乱行动。其中一个值得注意的计划是美洲学校,该学校成立于 1946 年,位于佐治亚州本宁堡。这所学校旨在培训拉丁美洲军事人员的反叛乱战术,其中包括教授酷刑和暗杀技巧。该校的许多毕业生后来成为拉美军事政权的领导人,其中一些人还卷入了侵犯人权和暴行。与此同时,美国还向拉美派遣绿色贝雷帽,对当地部队进行反叛乱战术培训。此外,"进步联盟 "是美国的一项经济援助计划,旨在促进该地区的经济和社会发展。这些举措是美国更广泛努力的一部分,旨在对抗苏联在拉丁美洲的影响,同时促进美国自身的利益和价值观。 | |||

随着共产主义的威胁在拉丁美洲日益加剧,美国政府将重点放在促进和巩固反共政权上,这往往以牺牲民主和人权为代价。这导致了对该地区一些专制和镇压性政权的支持,其中许多都对严重侵犯人权和政治压迫负有责任。美国向这些政权提供军事和经济援助,有时还以打击共产主义和促进美国利益的名义对其暴行视而不见。此外,美国还积极致力于颠覆和推翻那些被认为倾向于共产主义或社会主义意识形态的民选政府,如 1954 年的危地马拉和 1973 年的智利。尽管美国声称要促进该地区的民主和自由,但其行动往往产生相反的效果,导致许多国家的民主体制受到侵蚀,专制主义抬头。直到冷战结束和苏联解体后,美国才开始改变做法,优先支持该地区的民主治理和人权。这标志着美国在拉丁美洲的外交政策发生了重大变化。 | |||

冷战期间,美国政府相信,在反共斗争中,专制和镇压政权比民主政权更有效。因此,美国经常支持拉丁美洲的此类政权。其基本逻辑是,为了阻止共产主义的蔓延,美国需要支持有能力维护稳定和安全、愿意使用武力镇压共产主义运动及其同情者的政府。这种做法经常导致军政府和其他准备使用暴力和镇压手段来维持政权的独裁政权得到扶持。然而,这一战略却使该地区的人权和民主付出了相当大的代价。许多美国支持的政权都犯下了严重侵犯人权和政治镇压的罪行。此外,这一战略在防止共产主义蔓延方面也被证明是无效的。相反,它往往通过煽动民众对美国支持的政权的不满,助长了共产主义和社会主义运动的兴起。冷战结束、苏联解体后,美国才开始重新思考自己的做法,优先支持该地区的民主治理和人权。这标志着美国在拉丁美洲的外交政策发生了重大变化。 | |||

== | == 反民主浪潮(从 1947 年开始) == | ||

第二次世界大战后,许多拉丁美洲国家倾向于专制和不民主的做法。该地区的统治精英试图巩固权力,消灭反对派,包括中产阶级。这一发展在一定程度上受到冷战背景的影响,当时美国政府对反共政权的支持往往破坏了该地区的民主和人权。统治精英利用对共产主义威胁的认识,为其镇压反对派团体和持不同政见者寻找借口。因此,许多拉美国家出现了专制政权,军政府和其他镇压性政府掌权,普遍践踏人权。这种反民主趋势持续了几十年,直到冷战结束,标志着该地区开始向民主和尊重人权过渡。 | |||

[[File:Bogotazo.jpg|thumb| | [[File:Bogotazo.jpg|thumb|波哥大革命期间,国家议会大厦前着火的有轨电车。]] | ||

第二次世界大战后和冷战初期,拉丁美洲发生了一系列起义和政治危机,导致一些国家建立了独裁政权。在厄瓜多尔,1944 年的军事政变推翻了政府,建立了军政府。在秘鲁,20 世纪 40 年代末和 50 年代初的数次政变和政治危机导致 1968 年建立了军事政权。在委内瑞拉,1948 年的政变导致建立了军事独裁政权,并一直持续到 1958 年。除这些国家外,阿根廷和危地马拉的起义和政治危机也导致了独裁政权的建立。在阿根廷,1943 年的一场军事政变导致建立了军事独裁政权,并一直持续到 1946 年。此后,政局几度动荡,包括 20 世纪 70 年代和 80 年代初的 "肮脏战争"。在危地马拉,1954 年的政变推翻了民选政府,建立了军事独裁政权,并一直持续到 1985 年。这些独裁政权的特点往往是镇压、侵犯人权和镇压政治反对派。它们得到了美国的支持,美国将其视为该地区反对共产主义的堡垒。然而,最终事实证明它们难以为继,许多拉美国家自此开始向民主治理过渡。 | |||

在哥伦比亚,1946 年至 1954 年期间发生了一场由自由党和保守党之间的政治暴力引发的内战,被称为 "暴力"(La Violencia)。法西斯右翼在冲突中扮演了重要角色,保守势力对自由党反对派实施了屠杀和其他暴力行为。1946 年上台执政的保守党政府几乎没有采取任何措施来打击暴力,反而通过武装保守党准军事团体来助长冲突。这场内战造成至少 25 万人死亡,并在未来数年对哥伦比亚社会和政治产生了巨大影响。 | |||

在冷战时期的一些拉美国家,专制领导人往往在美国的支持下建立王朝。例如,在美国的支持下,福尔甘西奥-巴蒂斯塔(Fulgencio Batista)于 1934 年至 1940 年间独裁统治古巴,之后又于 1952 年至 1959 年间独裁统治古巴。在海地,以独裁者弗朗索瓦-杜瓦利埃和让-克洛德-杜瓦利埃父子为首的杜瓦利埃家族从 1957 年到 1986 年统治海地长达 30 多年。在尼加拉瓜,以阿纳斯塔西奥-索摩查-加西亚父子为首的索摩查家族在美国的支持下,从1936年到1979年控制该国长达40多年。这些独裁政权的特点往往是政治压迫、侵犯人权和迫害反对派,但他们凭借内部联盟和外部支持维持了多年政权。 | |||

尽管其他拉美国家面临着许多挑战和压力,乌拉圭仍被视为在冷战期间保持稳定和正常运作的民主国家。1942 年,乌拉圭成为第一个建立福利国家的拉美国家,并拥有悠久的民主和尊重人权的传统。冷战期间,乌拉圭组织了定期选举和多党政治制度。但在此期间,乌拉圭面临着政治和经济挑战,包括政治两极分化、社会动荡和经济停滞。20 世纪 70 年代,乌拉圭经历了一段以侵犯人权和镇压不同政见者为特征的独裁统治时期。然而,1985 年乌拉圭恢复了民主政府,自此以后,乌拉圭一直是一个稳定的民主国家,坚定地致力于人权和社会正义。这证明,尽管面临冷战的挑战,乌拉圭的民主体制仍具有顽强的生命力,乌拉圭人民愿意捍卫民主价值观。 | |||

虽然乌拉圭在冷战时期一直是民主国家,但值得注意的是,其他拉美国家也至少在一段时间内保持了民主政府。例如,哥斯达黎加有着悠久的民主传统,在冷战期间能够保持稳定的民主政府。智利在冷战时期的大部分时间里也有一个相对稳定的民主政府,尽管它面临着重大挑战,并最终在 1973 年经历了军事政变。墨西哥、巴西和委内瑞拉等其他国家在此期间也经历了民主政府时期,尽管这些时期往往政治不稳定,民主治理面临挑战。 | |||

== | == 拉丁美洲反共十字军东征的三个要素 == | ||

20 世纪 50 年代发生在拉丁美洲的 "反民主十字军东征 "包括三个主要内容,反映了在美国遏制政策的指导下,反对共产主义影响的激烈斗争。首先,这场 "讨伐 "最重要的一个方面是通过将共产党定为非法来消灭它们。这一措施产生了巨大影响,导致共产党员人数大幅减少。例如,共产党员人数从 1947 年的约 400 000 人减少到 1952 年的约一半。反共战略随后扩展到工作领域。美国政府与美国劳工联合会工会合作,在建立反共工会方面发挥了积极作用。此举旨在压制共产主义在劳工运动中的影响,而劳工运动通常被视为左翼思想的沃土。与此同时,共产党员被驱逐出已受国家控制的工会。最后,这场运动的第三个关键因素是外交排斥和在整个美洲断绝与苏联的外交关系。这一战略的目的是在政治上和外交上孤立该地区的共产党政府,防止苏联影响的扩散。从整体上看,这些措施旨在打击共产主义在拉丁美洲的影响,是美国在冷战期间推行的整体遏制政策的一部分。这一时期,地缘政治和意识形态紧张局势激烈,对相关国家造成了深远的社会和政治影响。 | |||

== The case of Guatemala == | == The case of Guatemala == | ||

[[File:Guatearbenz0870.JPG|right|thumb|150px| | [[File:Guatearbenz0870.JPG|right|thumb|150px|危地马拉城壁画上的雅各布-阿尔本斯-古斯曼(Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán)。]] | ||

[[File:CIA-Arbenz-overthrow-FOIA-documents-1of5.gif|thumb|right|150px| | [[File:CIA-Arbenz-overthrow-FOIA-documents-1of5.gif|thumb|right|150px|1954 年危地马拉 "政变":中央情报局备忘录(1975 年 5 月),其中描述了中央情报局在 1954 年 6 月罢黜雅各布-阿尔本斯-古斯曼总统的危地马拉政府中的作用(1-5)。]] | ||

Under the presidency of Jacobo Árbenz, elected in 1951, Guatemala underwent a series of reforms aimed at modernising the country and redistributing land. The agrarian reform, in particular, involved expropriating unused land from large landowners and distributing it to landless peasants. However, this policy affected American economic interests, notably those of the United Fruit Company, an American company that owned vast tracts of land in Guatemala. The US perception was that Árbenz's reforms not only threatened their economic interests but could also open the door to communist influence in the region. In 1954, this fear led the United States, under Eisenhower's administration, to organise a coup d'état against Árbenz. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) played a key role in providing financial, logistical and training support to Guatemalan exiles and local mercenaries to carry out the coup, known as Operation PBSUCCESS. The coup was successful, forcing Árbenz to resign and flee the country. In his place, a series of authoritarian military regimes were installed, marking the beginning of a long period of political repression and human rights violations in Guatemala. The Guatemalan episode clearly illustrates the willingness of the United States at that time to intervene in the political affairs of Latin America to protect its commercial interests and combat communism. It also shows their willingness to use clandestine operations and military force to achieve these objectives, even at the cost of overthrowing a democratically elected government. This event had profound repercussions not just for Guatemala but for the region as a whole, shaping international relations and the internal politics of many Latin American countries for decades to come. | Under the presidency of Jacobo Árbenz, elected in 1951, Guatemala underwent a series of reforms aimed at modernising the country and redistributing land. The agrarian reform, in particular, involved expropriating unused land from large landowners and distributing it to landless peasants. However, this policy affected American economic interests, notably those of the United Fruit Company, an American company that owned vast tracts of land in Guatemala. The US perception was that Árbenz's reforms not only threatened their economic interests but could also open the door to communist influence in the region. In 1954, this fear led the United States, under Eisenhower's administration, to organise a coup d'état against Árbenz. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) played a key role in providing financial, logistical and training support to Guatemalan exiles and local mercenaries to carry out the coup, known as Operation PBSUCCESS. The coup was successful, forcing Árbenz to resign and flee the country. In his place, a series of authoritarian military regimes were installed, marking the beginning of a long period of political repression and human rights violations in Guatemala. The Guatemalan episode clearly illustrates the willingness of the United States at that time to intervene in the political affairs of Latin America to protect its commercial interests and combat communism. It also shows their willingness to use clandestine operations and military force to achieve these objectives, even at the cost of overthrowing a democratically elected government. This event had profound repercussions not just for Guatemala but for the region as a whole, shaping international relations and the internal politics of many Latin American countries for decades to come. | ||

Version du 16 novembre 2023 à 14:42

根据 Aline Helg 的演讲改编[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

美洲独立前夕 ● 美国的独立 ● 美国宪法和 19 世纪早期社会 ● 海地革命及其对美洲的影响 ● 拉丁美洲国家的独立 ● 1850年前后的拉丁美洲:社会、经济、政策 ● 1850年前后的美国南北部:移民与奴隶制 ● 美国内战和重建:1861-1877 年 ● 美国(重建):1877 - 1900年 ● 拉丁美洲的秩序与进步:1875 - 1910年 ● 墨西哥革命:1910 - 1940年 ● 20世纪20年代的美国社会 ● 大萧条与新政:1929 - 1940年 ● 从大棒政策到睦邻政策 ● 政变与拉丁美洲的民粹主义 ● 美国与第二次世界大战 ● 第二次世界大战期间的拉丁美洲 ● 美国战后社会:冷战与富裕社会 ● 拉丁美洲冷战与古巴革命 ● 美国的民权运动

冷战是以美国为首的西方大国与以苏联为首的东方大国之间地缘政治长期紧张的时期。从第二次世界大战结束到 20 世纪 90 年代初,这一时代对全球政治和经济动态产生了重大影响。然而,拉丁美洲也未能幸免于这些地缘政治动荡,其历史在此期间受到了深刻影响。

由菲德尔-卡斯特罗领导的 1959 年古巴革命是这些动荡在拉丁美洲最重要的表现之一。它给该地区留下了不可磨灭的印记,被视为对美国利益的重大挑战。这场革命导致古巴建立了共产主义政权,被视为苏联在该地区影响力的延伸。因此,美国和古巴之间的关系恶化,出现了各种推翻古巴政府的企图,包括 1961 年臭名昭著的猪湾入侵失败。

古巴革命后,美国在拉丁美洲采取了干预政策,旨在阻止共产主义在该地区的蔓延。这一战略导致美国支持独裁政权,资助反共叛乱组织(如尼加拉瓜的康特拉),并支持军事政变(如 1973 年智利的军事政变)。不幸的是,美国的这种干涉往往导致该地区局势更加不稳定,人权遭到严重侵犯。

拉丁美洲的冷战

民主浪潮与美国干预(1944-1946 年)

第二次世界大战结束后的 1944 年至 1946 年期间,民主浪潮席卷了多个拉美国家。在这一时期,该地区出现了从独裁政权向民主政府的重大转变。有几个因素促成了这一政治变革。世界冲突的结束导致了国际政治的变化,全球范围内对民主和人权做出了坚定的承诺。民主价值观和人民自决是战后新的世界观的核心。美国在支持拉丁美洲民主方面发挥了关键作用。它鼓励该地区向民主过渡,特别是通过富兰克林-罗斯福总统的睦邻政策。西方民主国家,尤其是美国的成功,激励着许多拉丁美洲国家寻求更加民主的政府形式。公民渴望获得更大的政治自由,更多地参与决策过程。民间社会发起的社会运动、罢工和示威对现有的专制政权造成了巨大压力。拉丁美洲人民要求进行政治和社会改革,结束政治压迫。这导致一些拉美国家实现了民主转型,选举出了民主政府,并实施了重大政治改革。例如,阿根廷的胡安-多明戈-贝隆、巴西的欧里科-加斯帕尔-杜特拉、危地马拉的胡安-何塞-阿雷瓦洛当选总统,他们都支持民主政府和社会改革。

20 世纪 40 年代,拉丁美洲发生了几起重大政治事件,标志着该地区一些国家向民主过渡。1944 年,危地马拉发生军事政变,推翻了自 1931 年以来一直统治该国的豪尔赫-乌比科专制政府。这为建立民主政府铺平了道路,并激发了该地区其他类似的运动。1945 年,阿根廷举行民主选举,军官胡安-贝隆当选总统。这标志着阿根廷民主统治时期的开始,不过,1955 年贝隆在军事政变中被推翻,中断了这一时期。1946 年,巴西也举行了十多年来的首次民主选举,欧里科-加斯帕尔-杜特拉当选总统。这标志着自 1930 年以来执政的热图利奥-瓦加斯独裁统治的结束。秘鲁举行了民主选举,何塞-路易斯-布斯塔曼特-伊-里韦罗当选总统。他的政府推行了劳工改革,并将某些行业国有化。然而,该地区其他国家继续面临政治挑战。海地在埃利-莱斯科特总统的统治下,政府腐败严重,人权受到侵犯。在委内瑞拉,1945 年的人民起义推翻了伊萨亚斯-梅迪纳-安加里塔(Isaías Medina Angarita)的军事独裁统治,联合政府实施了进步政策和社会计划。然而,1948 年的一场军事政变又将该国推回到另一个独裁统治之下。这些事件说明了拉丁美洲国家在寻求民主和政治改革方面所走过的不同道路,反映了当时该地区的复杂性。

20 世纪 40 年代,拉丁美洲的民主过渡被该地区国家和美国普遍视为积极的发展。美国尤其支持这些变革,认为民主有助于促进政治稳定,打击共产主义在该地区的蔓延,这符合美国的冷战政策。然而,必须指出的是,这些过渡并非没有挑战。新的民主政体在建立后的几年里往往面临政治和经济不稳定的问题。民主过渡有时伴随着社会内部的政治紧张、冲突和分裂。刚刚摆脱长期独裁统治的国家往往需要重建对民主体制的信心,并找到处理政治分歧的方法。此外,该地区许多国家还面临着重大的经济挑战。向民主过渡并不能自动保证经济状况的改善,新的民主国家往往面临通货膨胀、外债和工业化薄弱等问题。外部压力和影响,特别是冷战期间来自美国和苏联的压力和影响,有时会使政治局势复杂化。该地区各国之间的地缘政治竞争也会影响其政治和经济取向。最后,社会运动和民众诉求有时是民主过渡的根源,在该地区的政治中继续发挥着重要作用。公民经常要求进行社会和经济改革,这可能会造成社会内部的紧张关系。归根结底,拉丁美洲的民主过渡是一个复杂的过程,既有成功也有困难。虽然民主带来了政治自由和公民参与方面的好处,但它并不总能解决该地区国家面临的所有经济和社会问题。在随后的几十年里,这些发展对拉丁美洲的政治和经济发展轨迹起到了关键作用。

与 1944 至 1946 年间席卷多个拉美国家的民主浪潮不同,古巴、洪都拉斯、尼加拉瓜、萨尔瓦多和巴拉圭在此期间仍处于独裁者的统治之下。这些独裁政权牢牢控制着各自的国家,对国家治理和公民日常生活造成了重大影响。在古巴,富尔亨西奥-巴蒂斯塔(Fulgencio Batista)掌权,最初当选为国家总统,但后来通过军事政变推翻了民主制度。其政权的特点是政治压迫和普遍腐败。在洪都拉斯,提布尔西奥-卡里亚斯-安迪诺(Tiburcio Carías Andino)自 1933 年以来一直维持独裁统治,对国家实行专制控制。阿纳斯塔西奥-索摩查-加西亚自 1937 年起作为独裁者统治尼加拉瓜,扼杀政治和经济权力,他的家族几十年来一直控制着这个国家。在萨尔瓦多,马克西米利亚诺-埃尔南德斯-马丁内斯将军自 1931 年以来一直掌权,他的政权因残酷镇压政治反对派而臭名昭著。巴拉圭由希吉尼奥-莫里尼戈领导,他在 1940 年的一次军事政变中上台执政,其政府以持续的独裁主义为特征。这些国家一直处于这些独裁者的控制之下,而该地区的其他国家则在向民主政府迈进。政治差异和国家背景造成了这些分歧,这些国家的人民经常面临镇压、侵犯人权以及限制政治和公民自由的时期。

1944 至 1946 年间拉丁美洲民主浪潮的特点是,城市中产阶级大力支持改良主义政党,这些政党往往得到共产主义和社会主义政党的支持。这些改良主义政党致力于推行旨在解决社会和经济不平等问题的进步政策,包括土地改革、劳工改革和社会计划。城市中产阶级尤其倾向于支持这些政党,因为他们渴望政治和经济现代化,而这些政党似乎承诺实现这一愿景。与此同时,共产党和社会主义政党也支持这些改革派政党,因为它们有着共同的社会和经济正义愿景。左翼政党将这些运动视为促进其财富再分配和社会改革理想的契机。然而,必须指出的是,共产党和社会主义政党对这些改革派政党的支持引起了美国的担忧。在冷战背景下,美国担心共产主义在拉丁美洲蔓延。美国将共产党和社会主义政党对改革运动的支持视为对其在该地区影响力的潜在威胁。这种担忧导致美国在二战后对多个拉美国家进行干预,目的是打击共产主义和社会主义运动,保护其地缘政治利益。20 世纪 40 年代拉丁美洲的民主浪潮是多种因素共同作用的结果,其中包括城市中产阶级对改革的渴望、对左翼政党的支持以及美国的地缘政治关切。这些动态给该地区留下了持久的印象,并影响了拉丁美洲随后的政治和经济发展。

第二次世界大战结束后,拉丁美洲经历了一个工业化复兴时期,其特点是渴望实现国民经济现代化,赶上欧洲和北美国家的发展步伐。这一时期经济增长的特点是新兴产业的出现、基础设施的发展和城市中产阶级的壮大。推动拉丁美洲工业化的因素很多,包括追求经济自给自足、国家经济多样化以及希望减少对原材料出口的依赖。该地区许多国家投资于制造业、机械化农业和交通基础设施等部门,以刺激经济增长。然而,美国在 20 世纪 40 年代末加入冷战对拉丁美洲产生了重大影响。美国和苏联之间的地缘政治斗争导致全球两极分化,该地区的许多国家都受到了这种竞争的影响。美国试图在拉丁美洲建立自己的影响力,以防止共产主义的蔓延,这往往导致对该地区的政治和军事干预。拉丁美洲成为冷战中的战略战场,该地区的国家往往分为亲美和亲苏阵营。美国支持反共政府和独裁者,而左翼运动和共产党也获得了影响力。冷战时期在拉丁美洲留下了持久的伤痕,其政治、经济和社会后果持续了几十年。地缘政治竞争有时凌驾于对经济发展和社会公正的关注之上,在该地区造成了深刻的分歧。

冷战期间,美国为遏制共产主义在拉丁美洲的蔓延,经常支持敌视民主原则和公民自由的独裁政权。这一政策导致该地区许多国家的民主长期衰落,军事独裁政权随之出现。这些独裁政权的特点是系统地侵犯人权、镇压政治反对派和强调军事集结。美国支持这些独裁政权的理由是,它们是防止共产主义蔓延的堡垒。然而,这一政策往往导致对公民基本权利的公然践踏,包括言论自由、新闻自由和参加自由公正选举的权利。许多美国支持的政府对政治机构实行严格控制,镇压一切形式的异议。这些军事独裁政权在许多拉美国家留下了深深的伤痕,对治理、人权和政治稳定造成了持久的影响。人权运动积极谴责这些弊端,在 20 世纪 80 年代和 90 年代向民主过渡的过程中,各国努力对过去的弊端做出解释,并建立更强大的民主制度。拉丁美洲的冷战历史错综复杂,其特点是地缘政治需要与民主价值观之间的微妙平衡。这一时期的后果对该地区产生了重大影响,在集体记忆中留下了深刻的痕迹,并影响了拉美国家的政治轨迹直至今日。

在此期间,美国向拉丁美洲的独裁政权提供了大量的军事和经济援助,这往往损害了民主原则和人权。美国在该地区推行的冷战政策产生了持久的影响,导致民主体制被削弱,社会不平等和社会冲突得以维持。美国的军事和经济援助往往被用来支持独裁政权,加强其内部镇压能力,并在反共斗争中推行有利于美国利益的政治导向。这种援助有时被用来镇压政治反对派和社会运动,助长了侵犯人权行为和政治不稳定。直到 20 世纪 80 年代和 90 年代,拉丁美洲才开始向民主过渡。军事独裁逐渐被民选政府取代,民间社会开始要求加强问责制和提高政治代表性。在这一过渡时期,人们努力追究独裁政权侵犯人权的责任,并进行旨在恢复民主和促进社会公正的改革。拉丁美洲的冷战历史仍然是该地区历史上复杂而有争议的一章,对政治、经济和社会产生了持久的影响。那个时代的教训有助于塑造 21 世纪拉丁美洲的政治轨迹,重新关注民主、人权和社会正义。

冷战的影响(1947 年)

1947 年,拉丁美洲在第二次世界大战后经历了一定程度的开放,但这一态势因美国加入冷战而戛然而止。这一时期,美国在该地区的军事力量得到加强,对地区政策产生了重大影响。在冷战背景下,美国采取了坚决反苏的政策,并在其主导的美洲国家间会议上努力向其他美洲国家宣传这一政策。这一时期的主要成就之一是 1947 年签署了《里约条约》。该条约建立了美洲国家之间的互助体系,并宣布对其中一个国家的任何武装攻击或威胁都将被视为对所有美洲国家的攻击。里约条约》加强了美国作为拉丁美洲霸主的地位,并为该地区的军事合作建立了框架。这也是美国遏制苏联在拉美地区的影响、防止共产主义在该地区蔓延的战略的重要工具。然而,加入该条约并非没有争议,因为许多拉美国家担心这会导致该地区过度军事化,削弱其国家主权。这一时期地缘政治紧张,竞争激烈,美国在冷战期间在确定拉丁美洲政治议程方面发挥了核心作用。

大多数拉美国家签署的《里约条约》的主要目的是遏制冷战期间共产主义在该地区扩张的威胁。该条约为签署国之间的军事合作建立了框架,美国在向这些国家的武装部队提供军事援助和培训方面发挥了核心作用。该条约还为美国干预拉美国家事务以保护其所认为的安全利益提供了理由。实际上,《里约条约》创建了一个集体防御机制,签署该条约的美洲国家承诺在发生武装侵略或安全威胁时相互支持。如果其中一个国家受到攻击,其他成员国有义务向其提供援助,从而巩固了美国作为该地区霸主的地位,并保证其在反共斗争中的领导地位。因此,《里约条约》成为冷战期间美国在拉丁美洲推行遏制政策的基石。它使美国有理由在该地区进行军事和政治干预,以对抗共产主义的影响,而这往往会损害国家主权和民主原则。这一时期的特点是美国强势介入拉美国家的内部事务,对该地区的政治和稳定产生了重大影响。

美国加入冷战并加强其在拉丁美洲的军事力量,对该地区产生了深远而持久的影响。这一时期加剧了对民主体制的侵蚀,强化了独裁军事政权的盛行,并增加了对人权的侵犯。美国推行的冷战政策往往损害了拉丁美洲的民主价值观和公民自由。得到美国支持的专制政府得到了大量支持,这有助于他们继续掌权,尽管他们采取了镇压行动。这些政权系统地侵犯人权,镇压政治反对派,并对公民社会施加严格限制。在这种情况下,酷刑、法外处决和媒体审查等公然侵权行为屡见不鲜。美国的影响也经常阻碍举行自由公正的选举,破坏该地区的民主。拉丁美洲花了许多年才从这一政治动荡和镇压时期恢复过来。20 世纪 80 年代和 90 年代的民主过渡标志着一个重要的转折点,人们努力对过去的侵权行为进行问责、恢复民主和促进人权。然而,这一时期的后果却一直存在,在该地区的集体记忆中留下了深深的伤痕,并对拉丁美洲的政治和社会产生了持久的影响。

冷战期间,美国认为自己受到苏联和共产主义意识形态的攻击。在此背景下,美国政府认为拉丁美洲是一个容易受到共产主义影响的地区,并将共产主义在该地区的传播视为对其自身安全的威胁。因此,美国采取了各种手段,试图拉拢拉美国家支持其反共事业。美国向其认为有利于自身利益的政权提供军事和经济援助,同时积极推翻其认为是共产主义或同情共产主义的政府。他们还利用宣传来推广自己的世界观,将共产主义及其支持者妖魔化,并影响该地区的公众舆论。许多拉美国家感受到了在反冷战斗争中与美国结盟的压力,即使它们并不完全赞同美国的观点或利益。一些国家,如古巴和尼加拉瓜,明确反对美国的世界观,并采取了反美政策。然而,该地区大多数国家发现自己处于一个微妙的位置,既要努力维护自己的独立和主权,又要在反共斗争中与美国保持一致。这种态势对拉丁美洲产生了重大影响。它导致了民主体制的削弱、社会冲突和不平等的长期存在,以及美国支持的独裁政权的盛行。美国在反冷战斗争中拉拢拉美国家支持其事业的努力往往是以牺牲该地区的民主价值观和人权为代价的。拉美花了很多年才从这段政治动荡和镇压时期恢复过来,对该地区的政治、经济和社会造成了持久影响。20 世纪 80 年代和 90 年代的民主过渡标志着该地区历史上的一个重要里程碑,人们努力对过去的侵权行为做出解释,并建立更加尊重人权的更强大的民主制度。

美洲国家组织(OAS)总部位于华盛顿特区的泛美联盟大厦。该大厦建成于 1910 年,是美洲国家组织的前身美洲共和国国际联盟的总部所在地。如今,这座标志性建筑是美洲国家组织的主要行政中心,也是世界上历史最悠久的区域组织。美洲国家组织成立于 1948 年,旨在促进美洲的民主、人权和经济发展。该组织汇集了来自北美洲、中美洲、南美洲和加勒比海地区的 35 个成员国。它在该地区成员国之间的合作和政策协调方面发挥着至关重要的作用,致力于保护人权、促进民主、解决冲突和社会经济发展等问题。美洲国家组织是众多旨在加强美洲政治稳定和尊重民主价值观的辩论和倡议的论坛。美洲国家组织总部设在华盛顿特区,体现了其作为促进美洲国家间合作与理解的重要地区组织的重要性。

美洲国家组织(OAS)成立于 1948 年,是一个旨在促进美洲国家间合作与团结的地区性组织。然而,虽然《美洲国家组织宪章》规定了不干涉和不干预原则,但现实情况是,美国经常主导该组织。在整个冷战期间,美国利用美洲国家组织作为促进其在该地区利益的工具,常常损害其他成员国的主权和独立。美洲国家组织于 1962 年通过了一项决议,宣布共产主义与民主不相容,这给美国和其他成员国提供了一个借口,可以干涉被认为同情共产主义的其他国家的内政。此外,由于美国在该地区的经济和军事实力,以及该组织总部设在华盛顿特区这一事实,美国在美洲国家组织内历来具有相当大的影响力。这常常导致有人指责美洲国家组织偏袒美国,并被用来促进美国在该地区的利益。尽管有这些批评,美洲国家组织还是促进了美洲的民主和人权,并在调解成员国之间的冲突方面发挥了关键作用。近年来,该组织一直在努力重申其独立性,并促进以更加平衡的方式处理地区问题。然而,美国主导美洲国家组织的历史仍是该地区的争议焦点。

20 世纪 60 年代,美国将拉丁美洲视为全球反共斗争的潜在战场。他们担心苏联在该地区扩张的可能性。这种观点受到多种因素的影响,尤其是 1959 年的古巴革命,这场革命在距离美国海岸仅 90 英里的地方建立了一个社会主义政府。1947 年的《里约条约》规定,任何对美洲成员国安全或领土完整的威胁都将被视为对所有成员国的威胁。这意味着,如果该地区的任何国家受到外来势力的攻击或威胁,美国将有义务保护该国。这被视为一种威慑来自地区外的侵略和促进地区团结以应对共同威胁的方式。然而,随着冷战的发展,美国开始对这一条款进行更宽泛的解释,认为对成员国安全的任何内部威胁,如共产主义的传播,也会威胁到美国。这种解释为美国干涉地区其他国家的内政提供了借口,而这些国家的主权或独立往往很少受到重视。在此背景下,美国越来越多地参与支持该地区的反共力量,特别是通过军事援助和培训、秘密行动和直接干预冲突。这导致了一系列有争议、有时甚至是血腥的干预行动,包括在危地马拉、尼加拉瓜和智利。

门罗主义由詹姆斯-门罗总统于1823年首次提出,宣称美国反对欧洲列强殖民或干涉西半球国家事务的任何企图。随着时间的推移,这一理论被解释为美国干预拉丁美洲的理由,特别是在冷战期间。在此期间,美国国会投票赞成向拉美国家提供军事援助,通常采取经济和军事援助计划的形式。这些援助旨在加强这些国家的军事能力,遏制苏联在该地区的影响。然而,这些资金的很大一部分被用于购买美国制造的武器和军事装备,从而刺激了美国国防工业的发展。美国的军事援助往往带有附加条件,因为美国试图在拉美地区促进自己的利益和价值观。这包括鼓励民主、人权以及反对左翼运动和政府。然而,在某些情况下,美国的军事援助被用来支持专制独裁政权,导致该地区国家出现侵犯人权和政治压迫的现象。

冷战期间,美国向拉美国家提供的军事援助具有重要意义。这种援助采取一揽子经济和军事援助的形式,旨在加强拉美国家抵御内部和外部威胁的防御能力。然而,这些援助中有相当一部分被指定用于购买美国制造的武器和军事装备,这有助于刺激美国国防工业的发展。这种做法也是美国通过加强地区盟国的军事能力来促进其利益和价值观的一种方式。这种态势在多个领域产生了重大影响。首先,它使美国成为全球军火贸易的主要参与者,为专门从事军火生产的美国公司创造了就业机会和收入。它还加强了拉美国家在军事和安全支持方面对美国的依赖,从而巩固了美国在该地区的影响力。然而,武器在该地区的扩散也助长了许多国家的内部冲突和不稳定,使冷战期间美国对拉美的军事援助产生了复杂而持久的后果。

除了美国的军事援助和武器销售,冷战期间美国还在拉丁美洲实施了各种培训计划和反叛乱行动。其中一个值得注意的计划是美洲学校,该学校成立于 1946 年,位于佐治亚州本宁堡。这所学校旨在培训拉丁美洲军事人员的反叛乱战术,其中包括教授酷刑和暗杀技巧。该校的许多毕业生后来成为拉美军事政权的领导人,其中一些人还卷入了侵犯人权和暴行。与此同时,美国还向拉美派遣绿色贝雷帽,对当地部队进行反叛乱战术培训。此外,"进步联盟 "是美国的一项经济援助计划,旨在促进该地区的经济和社会发展。这些举措是美国更广泛努力的一部分,旨在对抗苏联在拉丁美洲的影响,同时促进美国自身的利益和价值观。

随着共产主义的威胁在拉丁美洲日益加剧,美国政府将重点放在促进和巩固反共政权上,这往往以牺牲民主和人权为代价。这导致了对该地区一些专制和镇压性政权的支持,其中许多都对严重侵犯人权和政治压迫负有责任。美国向这些政权提供军事和经济援助,有时还以打击共产主义和促进美国利益的名义对其暴行视而不见。此外,美国还积极致力于颠覆和推翻那些被认为倾向于共产主义或社会主义意识形态的民选政府,如 1954 年的危地马拉和 1973 年的智利。尽管美国声称要促进该地区的民主和自由,但其行动往往产生相反的效果,导致许多国家的民主体制受到侵蚀,专制主义抬头。直到冷战结束和苏联解体后,美国才开始改变做法,优先支持该地区的民主治理和人权。这标志着美国在拉丁美洲的外交政策发生了重大变化。

冷战期间,美国政府相信,在反共斗争中,专制和镇压政权比民主政权更有效。因此,美国经常支持拉丁美洲的此类政权。其基本逻辑是,为了阻止共产主义的蔓延,美国需要支持有能力维护稳定和安全、愿意使用武力镇压共产主义运动及其同情者的政府。这种做法经常导致军政府和其他准备使用暴力和镇压手段来维持政权的独裁政权得到扶持。然而,这一战略却使该地区的人权和民主付出了相当大的代价。许多美国支持的政权都犯下了严重侵犯人权和政治镇压的罪行。此外,这一战略在防止共产主义蔓延方面也被证明是无效的。相反,它往往通过煽动民众对美国支持的政权的不满,助长了共产主义和社会主义运动的兴起。冷战结束、苏联解体后,美国才开始重新思考自己的做法,优先支持该地区的民主治理和人权。这标志着美国在拉丁美洲的外交政策发生了重大变化。

反民主浪潮(从 1947 年开始)

第二次世界大战后,许多拉丁美洲国家倾向于专制和不民主的做法。该地区的统治精英试图巩固权力,消灭反对派,包括中产阶级。这一发展在一定程度上受到冷战背景的影响,当时美国政府对反共政权的支持往往破坏了该地区的民主和人权。统治精英利用对共产主义威胁的认识,为其镇压反对派团体和持不同政见者寻找借口。因此,许多拉美国家出现了专制政权,军政府和其他镇压性政府掌权,普遍践踏人权。这种反民主趋势持续了几十年,直到冷战结束,标志着该地区开始向民主和尊重人权过渡。

第二次世界大战后和冷战初期,拉丁美洲发生了一系列起义和政治危机,导致一些国家建立了独裁政权。在厄瓜多尔,1944 年的军事政变推翻了政府,建立了军政府。在秘鲁,20 世纪 40 年代末和 50 年代初的数次政变和政治危机导致 1968 年建立了军事政权。在委内瑞拉,1948 年的政变导致建立了军事独裁政权,并一直持续到 1958 年。除这些国家外,阿根廷和危地马拉的起义和政治危机也导致了独裁政权的建立。在阿根廷,1943 年的一场军事政变导致建立了军事独裁政权,并一直持续到 1946 年。此后,政局几度动荡,包括 20 世纪 70 年代和 80 年代初的 "肮脏战争"。在危地马拉,1954 年的政变推翻了民选政府,建立了军事独裁政权,并一直持续到 1985 年。这些独裁政权的特点往往是镇压、侵犯人权和镇压政治反对派。它们得到了美国的支持,美国将其视为该地区反对共产主义的堡垒。然而,最终事实证明它们难以为继,许多拉美国家自此开始向民主治理过渡。

在哥伦比亚,1946 年至 1954 年期间发生了一场由自由党和保守党之间的政治暴力引发的内战,被称为 "暴力"(La Violencia)。法西斯右翼在冲突中扮演了重要角色,保守势力对自由党反对派实施了屠杀和其他暴力行为。1946 年上台执政的保守党政府几乎没有采取任何措施来打击暴力,反而通过武装保守党准军事团体来助长冲突。这场内战造成至少 25 万人死亡,并在未来数年对哥伦比亚社会和政治产生了巨大影响。

在冷战时期的一些拉美国家,专制领导人往往在美国的支持下建立王朝。例如,在美国的支持下,福尔甘西奥-巴蒂斯塔(Fulgencio Batista)于 1934 年至 1940 年间独裁统治古巴,之后又于 1952 年至 1959 年间独裁统治古巴。在海地,以独裁者弗朗索瓦-杜瓦利埃和让-克洛德-杜瓦利埃父子为首的杜瓦利埃家族从 1957 年到 1986 年统治海地长达 30 多年。在尼加拉瓜,以阿纳斯塔西奥-索摩查-加西亚父子为首的索摩查家族在美国的支持下,从1936年到1979年控制该国长达40多年。这些独裁政权的特点往往是政治压迫、侵犯人权和迫害反对派,但他们凭借内部联盟和外部支持维持了多年政权。

尽管其他拉美国家面临着许多挑战和压力,乌拉圭仍被视为在冷战期间保持稳定和正常运作的民主国家。1942 年,乌拉圭成为第一个建立福利国家的拉美国家,并拥有悠久的民主和尊重人权的传统。冷战期间,乌拉圭组织了定期选举和多党政治制度。但在此期间,乌拉圭面临着政治和经济挑战,包括政治两极分化、社会动荡和经济停滞。20 世纪 70 年代,乌拉圭经历了一段以侵犯人权和镇压不同政见者为特征的独裁统治时期。然而,1985 年乌拉圭恢复了民主政府,自此以后,乌拉圭一直是一个稳定的民主国家,坚定地致力于人权和社会正义。这证明,尽管面临冷战的挑战,乌拉圭的民主体制仍具有顽强的生命力,乌拉圭人民愿意捍卫民主价值观。

虽然乌拉圭在冷战时期一直是民主国家,但值得注意的是,其他拉美国家也至少在一段时间内保持了民主政府。例如,哥斯达黎加有着悠久的民主传统,在冷战期间能够保持稳定的民主政府。智利在冷战时期的大部分时间里也有一个相对稳定的民主政府,尽管它面临着重大挑战,并最终在 1973 年经历了军事政变。墨西哥、巴西和委内瑞拉等其他国家在此期间也经历了民主政府时期,尽管这些时期往往政治不稳定,民主治理面临挑战。

拉丁美洲反共十字军东征的三个要素

20 世纪 50 年代发生在拉丁美洲的 "反民主十字军东征 "包括三个主要内容,反映了在美国遏制政策的指导下,反对共产主义影响的激烈斗争。首先,这场 "讨伐 "最重要的一个方面是通过将共产党定为非法来消灭它们。这一措施产生了巨大影响,导致共产党员人数大幅减少。例如,共产党员人数从 1947 年的约 400 000 人减少到 1952 年的约一半。反共战略随后扩展到工作领域。美国政府与美国劳工联合会工会合作,在建立反共工会方面发挥了积极作用。此举旨在压制共产主义在劳工运动中的影响,而劳工运动通常被视为左翼思想的沃土。与此同时,共产党员被驱逐出已受国家控制的工会。最后,这场运动的第三个关键因素是外交排斥和在整个美洲断绝与苏联的外交关系。这一战略的目的是在政治上和外交上孤立该地区的共产党政府,防止苏联影响的扩散。从整体上看,这些措施旨在打击共产主义在拉丁美洲的影响,是美国在冷战期间推行的整体遏制政策的一部分。这一时期,地缘政治和意识形态紧张局势激烈,对相关国家造成了深远的社会和政治影响。

The case of Guatemala

Under the presidency of Jacobo Árbenz, elected in 1951, Guatemala underwent a series of reforms aimed at modernising the country and redistributing land. The agrarian reform, in particular, involved expropriating unused land from large landowners and distributing it to landless peasants. However, this policy affected American economic interests, notably those of the United Fruit Company, an American company that owned vast tracts of land in Guatemala. The US perception was that Árbenz's reforms not only threatened their economic interests but could also open the door to communist influence in the region. In 1954, this fear led the United States, under Eisenhower's administration, to organise a coup d'état against Árbenz. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) played a key role in providing financial, logistical and training support to Guatemalan exiles and local mercenaries to carry out the coup, known as Operation PBSUCCESS. The coup was successful, forcing Árbenz to resign and flee the country. In his place, a series of authoritarian military regimes were installed, marking the beginning of a long period of political repression and human rights violations in Guatemala. The Guatemalan episode clearly illustrates the willingness of the United States at that time to intervene in the political affairs of Latin America to protect its commercial interests and combat communism. It also shows their willingness to use clandestine operations and military force to achieve these objectives, even at the cost of overthrowing a democratically elected government. This event had profound repercussions not just for Guatemala but for the region as a whole, shaping international relations and the internal politics of many Latin American countries for decades to come.

At the time, Guatemala's population of just over 3 million was largely made up of indigenous Mayans. Despite their numbers, these Mayan communities lived in conditions of poverty and had limited access to essential services such as education and healthcare. Guatemala's economy was heavily based on agriculture, particularly the export of coffee and bananas. The presence of the United Fruit Company, a powerful American company with close links to the US government, had a significant impact on the country's economy and politics. The company held a large share of the agricultural land, particularly that used for banana cultivation, and played a major role in the banana industry. The concentration of land and wealth in the hands of a few large companies and the local elite contributed to a worsening of social inequalities. The indigenous Mayan population, in particular, was marginalised, often dispossessed of its land and deprived of the benefits of the country's natural wealth. This unequal socio-economic structure was one of the triggers for the reforms undertaken by the government of Jacobo Árbenz, including the agrarian reform aimed at redistributing land to landless peasants, many of whom came from Mayan communities. The Guatemalan context of this period, characterised by deep inequalities and significant foreign influence, played a crucial role in the country's political and social events, including the 1954 coup d'état. These historical aspects continue to influence contemporary Guatemalan society, with repercussions that are still felt today.

Juan José Arévalo was elected President of Guatemala in 1944 following the "October Revolution", a popular uprising that overthrew the military dictatorship in power. His election marked a historic turning point, as he became the country's first democratically elected president. During his time in office, Arévalo initiated a number of progressive reforms, which laid the foundations for significant social and economic change. These reforms included improvements in working conditions, the creation of social security and embryonic land reform. Although his reforms were moderate, they laid the groundwork for the more radical changes that were to follow. Arévalo's presidency was followed by that of Jacobo Árbenz, who continued and intensified the reforms initiated by his predecessor. Árbenz is best known for his ambitious land reform programme, which aimed to expropriate unused land belonging to large companies, including the United Fruit Company, and redistribute it to landless peasants. This policy directly affected American economic interests and investments in Guatemala. The expropriation of United Fruit Company land was perceived as a threat by the United States, not only because of the potential economic losses but also because of fears of communist influence in the region. These concerns led the Eisenhower administration to authorise a covert operation, orchestrated by the CIA, to overthrow the Árbenz government in 1954. The coup was successful and marked the beginning of a period of political unrest and repression in Guatemala, ending a brief period of democratisation and progressive reform. The story of Juan José Arévalo and Jacobo Árbenz and the events that followed their terms of office reveal the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War and the profound impact of foreign interventionism, particularly American, in the political affairs of Latin America. These events had a lasting impact on Guatemala, shaping its political and social development for decades.

Juan José Arévalo's term as President of Guatemala was characterised by a series of progressive reforms that marked a period of modernisation and social advancement in the country. Under his leadership, a new constitution was adopted, inspired by that of Mexico. This constitution provided guarantees for a wide range of civil and political rights, significantly strengthening protections for Guatemalan citizens. It established a legal framework for democracy and human rights, laying the foundations for a fairer society. At the same time, Arévalo introduced a modern labour code. This code granted important rights to workers, such as collective bargaining and limiting the working day to eight hours. These measures represented a major advance in labour rights, radically changing the working conditions that had previously prevailed. In addition to these legal and social reforms, the Arévalo government also launched an ambitious literacy campaign. This initiative aimed to reduce the high illiteracy rate in Guatemala by improving access to education for a large proportion of the population. The aim was to enable Guatemalan citizens to acquire the skills essential for active participation in the country's economic, social and political life. These reforms have had a considerable impact on Guatemalan society, improving the living conditions of many citizens and laying the foundations for a more equitable and democratic society. Although Arévalo's efforts faced various challenges, including opposition from some sectors of society and foreign interests, they marked a crucial step in the development of modern Guatemala.

The presidency of Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala, which began in 1951, was marked by ambitions to modernise and emancipate the country from the influence of foreign interests. His aim was to follow a capitalist model while reaffirming national sovereignty. Its main policy was the implementation of an ambitious agrarian reform. This reform aimed to nationalise unused land held by foreign companies, notably the United Fruit Company, and redistribute it to landless Guatemalan peasants. The idea was to tackle the country's deep-rooted land and social inequalities, thereby offering a better life opportunity to disadvantaged rural populations. However, this initiative had a direct impact on the economic interests of the United States and offended the Guatemalan elites, who were closely linked to large foreign companies and wealthy landowners. These reforms aroused concern and mistrust in the United States, which perceived the Árbenz government not only as a threat to its commercial interests, but also as a possible ally of communism in the region. These tensions eventually led President Eisenhower's administration to take drastic measures. In 1954, the United States orchestrated a coup d'état against Árbenz, fearing that his policies would encourage the spread of Communist influence in the Western Hemisphere. This intervention put an end to Árbenz's government and ushered in a period of political unrest and repression in Guatemala, marking a decisive turning point in the country's history.

The agrarian reform introduced by President Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala was a bold response to the profound inequalities in land ownership that characterised the country at the time. A small fraction of the population, barely 2%, owned around 70% of the arable land. This extreme concentration of land ownership left the vast majority of peasants without land or with very small plots that were insufficient to meet their needs. The aim of the reform was to redistribute unused land from large plantations to poor peasants and small farmers, in order to correct these imbalances. The land reform law allowed for the expropriation of unused land from large landowners, while providing for compensation based on the declared value of the property for tax purposes. The underlying idea was to make this land productive, to increase the country's agricultural productivity, and to encourage a fairer and more balanced distribution of land. However, this initiative met with strong opposition, particularly from the United Fruit Company (UFC), a powerful American company that owned huge tracts of land in Guatemala. Agrarian reform posed a direct threat to the interests of the UFC, which feared losing a large proportion of its land to redistribution. To counter this policy, the United Fruit Company exerted intense pressure on the US government. It presented agrarian reform as a communist-inspired initiative and as a direct threat to American economic and strategic interests in the region. This lobbying campaign, combined with the growing perception of Guatemala as fertile ground for communist influence, eventually convinced the US to act. As a result, in 1954, with US support, a coup was orchestrated to overthrow President Árbenz. This intervention not only put an end to agrarian reform, but also triggered a period of repression and political instability that would mark Guatemala for decades to come. The Árbenz agrarian reform remains an emblematic example of the complexity of structural reforms in a context of geopolitical tensions and powerful economic interests.

In 1944, after 13 years of dictatorship, Juan José Arévalo was elected President of Guatemala at the end of a period of political turmoil. He was the bearer of an ambitious programme to democratise and modernise the country. Under his presidency, Guatemala underwent significant changes, including the adoption of a new constitution and the introduction of a modern labour code. At the same time, a vast literacy campaign was launched to educate a largely illiterate population. After Arévalo's term in office, Jacobo Arbenz, a centre-left leader, was elected president. His aim was to transform Guatemala into an independent state with a modern capitalist economy. In 1952, Arbenz initiated a bold agrarian reform that authorised the expropriation of uncultivated land from large plantations, in return for compensation paid by the government. This reform had a considerable impact, resulting in the distribution of around 700,000 hectares of land to some 18,000 landless peasant families. However, Arbenz's land reform provoked fierce opposition, particularly from the United Fruit Company (UFC), an American company that owned huge tracts of land in Guatemala. Much of this land was fallow, reserved for the company's future expansion, which placed it in direct conflict with the aims of agrarian reform. The UFC's opposition and influence on the US government ultimately played a key role in subsequent political events, including the 1954 coup d'état that toppled the Arbenz government.

The Guatemalan government, led by President Jacobo Árbenz, offered compensation of 627,000 dollars to the United Fruit Company for the expropriation of its uncultivated land, in accordance with its agrarian reform. This sum was based on the tax value declared by the company itself. However, the offer was strongly contested. Inside Guatemala, many citizens supported the agrarian reform and saw the compensation as fair, given that it was based on the United Fruit Company's own valuation. However, the company and its allies rejected the offer as being grossly inadequate. They felt that the real value of the land was much higher than that declared for tax purposes. Internationally, and particularly in the United States, this proposal exacerbated tensions. The US government, influenced by the close links between the United Fruit Company and some of its members, perceived this reform as a potential threat to US commercial interests in the region. In addition, in the context of the Cold War, accusations of communism were made against the Árbenz government. These allegations, often exaggerated or unsubstantiated, fuelled concern and were used to justify opposition to land reform and, ultimately, US intervention in Guatemalan affairs. These tensions and accusations helped to create a climate of mistrust and conflict, laying the foundations for the 1954 coup d'état, which overthrew the Árbenz government and put an end to its agrarian reform. This CIA-backed coup marked a major turning point in Guatemala's history and had a profound impact on Guatemalan politics and society in the decades that followed.

The US government reacted vigorously to the agrarian reform of the Guatemalan government led by President Jacobo Árbenz, particularly because of the expropriation of United Fruit Company land. The US government, under pressure from the United Fruit Company, demanded far more compensation than Guatemala had offered, up to 25 times the initial amount. This disproportionate demand reflected the United States' desire to protect the commercial interests of the United Fruit Company, a company with close links to senior US officials. At the same time, accusations of communism were made against President Arbenz. These accusations were largely motivated by Cold War rhetoric and were often exaggerated. Nevertheless, they served as a convenient pretext for the US government to justify its intervention in Guatemala. The idea that Guatemala might fall into Soviet hands was unacceptable to the United States, which sought to stem Communist influence in the Western Hemisphere. Against this backdrop, the CIA was authorised to carry out covert operations against the Árbenz government. These operations included the supply of weapons and training to Guatemalan opponents, as well as the infiltration of the Guatemalan army by American agents. These preparations laid the foundations for a coup d'état against President Arbenz. The coup, known as "Operation PBSUCCESS", was launched in 1954. It led to the overthrow of Arbenz and the installation of a government more favourable to American interests. The coup had far-reaching consequences for Guatemala, plunging the country into a period of political turmoil and internal conflict that lasted for decades.

US foreign policy during this period was heavily influenced by the domino theory, according to which the fall of one country into communism could lead to a chain reaction, with other countries following suit. This was particularly worrying in Latin America, where several countries were experiencing political instability and revolutionary movements. Guatemala was seen as a potential precursor. The US feared that a successful left-wing government in Guatemala could become a model for other countries in the region. This could, it was argued, encourage and strengthen other leftist movements in Latin America, threatening pro-US governments and US influence in the hemisphere. Strategic concerns about the Panama Canal also played a role. The Canal was crucial to US trade and military operations, and any change in the balance of power in Central America was seen as a potential risk to the control and security of the waterway. Against this backdrop, US strategy in Latin America, and the world in general, focused on containing communism. This strategy was part of the wider Cold War, in which the United States and the Soviet Union struggled for global influence. Interventions in Latin America, such as the one in Guatemala, were seen as necessary measures to prevent the spread of Soviet and Communist influence in the Western Hemisphere.

The intervention in Guatemala in 1954 is a classic example of direct US involvement in the political affairs of a Latin American country during the Cold War. The operation, known as "Operation PBSuccess", was orchestrated by the CIA and marked a significant turning point in Guatemala's history. Despite the lack of support from the Organisation of American States (OAS) for military intervention, the CIA planned an attack from Honduras, involving Guatemalan exiles. The operation was relatively small in terms of troops, but was reinforced by a campaign of disinformation and psychological warfare to sow confusion and fear among Arbenz's supporters and the Guatemalan army. Arbenz's resignation paved the way for a series of US-backed military regimes to rule Guatemala for decades. These regimes were often characterised by severe repression, human rights violations and widespread political violence. This event is often cited as an example of US interventionism in the internal affairs of Latin American countries during this period. It illustrates how US strategic and anti-communist priorities during the Cold War sometimes led to the support of authoritarian regimes and the destabilisation or overthrow of democratically elected governments.

Jacobo Arbenz, after being forced to resign following the CIA-orchestrated coup d'état, was forced into exile. His accusations against the United Fruit Company and the US government were in tune with the realities of the time, when US commercial interests and the fight against communism were often closely linked in US foreign policy. The fall of Arbenz ushered in a dark period for Guatemala. The military regimes that followed were characterised by brutal repression, massive human rights violations and a lack of democratic freedoms. This period was also marked by a prolonged internal armed conflict, which lasted from 1960 until the peace accords of 1996. This conflict claimed hundreds of thousands of victims, particularly among the indigenous population, and left deep scars on Guatemalan society. The case of Guatemala is often cited as an example of the harmful effects of foreign interventionism, particularly in the context of the Cold War, when the fight against Soviet influence sometimes justified actions that had disastrous humanitarian and political consequences for the target countries.

The period following the fall of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala was marked by brutal repression and the reversal of many progressive policies put in place under his administration. The military regime that took power with US support quickly reversed land reform, re-establishing the pre-existing unequal land structure and favouring the interests of big business such as the United Fruit Company. Political repression was severe, with arrests, executions and disappearances of those considered threats to the regime, including activists, intellectuals, trade unionists and others suspected of communist sympathies. Cultural censorship, exemplified by the banning of classics such as Victor Hugo's 'Les Misérables', reflected a climate of intellectual oppression and fear of any form of dissent or social criticism. Serious human rights violations during this period, with thousands of people killed or disappeared, laid the foundations for a prolonged and bloody internal conflict. This conflict exacerbated social and political divisions and had a devastating impact on the Guatemalan population, particularly on indigenous communities. Guatemala's history during this period is a sombre reminder of the consequences of foreign interventionism and the primacy of geopolitical and economic interests over human rights and democracy. The scars left by this period continue to influence Guatemalan society to this day.

Bolivia during the period of the National Revolution (1952-1964) offers a fascinating example of an attempt at social and economic transformation in a complex geopolitical context, marked by the Cold War. The actions undertaken by the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR) reflect the aspirations of a large part of the Bolivian population at the time, eager to break away from the oppressive socio-economic structures that had prevailed for decades. The nationalisation of the tin mines was a significant step towards the recovery of national resources. Bolivia was one of the world's leading tin producers, and the mines were largely controlled by foreign interests. However, this nationalisation also caused tensions with the United States and other countries whose companies were affected. At the same time, agrarian reform aimed to redistribute land from large landowners to landless peasants, a radical change in a country where land inequalities were extreme. Although implementation was uneven, this reform changed the rural landscape of Bolivia. Another revolutionary aspect of this period was the extension of citizenship and voting rights to indigenous peoples, breaking centuries of exclusion and marginalisation. In addition, investment in education and healthcare was aimed at improving the standard of living of the poorest sections of society. However, these reforms encountered numerous obstacles. Opposition from Bolivia's business elite, pressure from foreign interests and domestic economic difficulties undermined many of the MNR's initiatives. In addition, Bolivia continued to face chronic political instability, with frequent coups d'état and periods of authoritarian rule. Despite these challenges, the National Revolution left an indelible mark on Bolivian history. It paved the way for greater political participation by marginalised populations and laid the foundations for future struggles for social and economic justice. Although the reform was not as radical or lasting as some would have wished, it demonstrated the possibility of substantial change in the face of considerable obstacles.

The Cuban Revolution

Prelude to the revolution: Cuba under Batista

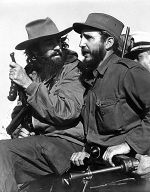

The Cuban Revolution, led by Fidel Castro and his followers in the Sierra Maestra, is an emblematic example of successful guerrilla warfare. Initially, this small group of poorly equipped rebels seemed unlikely to overthrow the established regime. However, thanks to a combination of key factors, they were able to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles. The Sierra Maestra itself played a crucial role in providing difficult terrain for Batista's government forces. This mountainous region served as a natural bastion, allowing the guerrillas to hide, regroup and plan their actions with a relative degree of security. Fidel Castro, as a charismatic leader, was a determining factor in the success of the revolution. His charisma and ability to articulate a clear vision of a better future for Cuba rallied many supporters to his cause. The promise of overthrowing the Batista dictatorship, seen as corrupt and oppressive, resonated deeply with the Cuban people. The guerrilla strategy employed by the rebels was adapted to their situation. Avoiding direct confrontation with a government army superior in numbers and equipment, they opted for rapid attacks, ambushes and guerrilla tactics that gradually exhausted and demoralised their opponents. The capture of weapons and military equipment from Batista's forces also played a crucial role. Each guerrilla victory often resulted in the seizure of precious resources, strengthening their fighting capacity. Finally, the support of the Soviet Union and other socialist countries was a major asset for the guerrillas. This support took various forms, including military supplies, training and diplomatic assistance. Taken together, these factors - perseverance, an effective guerrilla strategy, popular support, a charismatic leader, and foreign assistance - converged to enable Fidel Castro and his followers to overthrow the Batista regime and establish a new government in Cuba.

Fulgencio Batista's seizure of power in Cuba in a coup d'état in 1952 ushered in an era of authoritarianism and repression. Although Batista had already been President of Cuba in the 1940s, his return to power was characterised by further consolidation of power and a blatant disregard for democracy and human rights. Corruption was rampant under his regime, with Batista and his inner circle profiting economically. US companies, particularly those linked to the sugar industry, had large investments in Cuba and benefited from the US government's support for Batista. This relationship fuelled mistrust and resentment among many Cubans, who saw the United States as the accomplice of an oppressive dictator. Political repression, censorship and violence against the opposition were key elements of Batista's regime. In the face of this oppression, opposition to his government took many forms, from traditional political parties to guerrilla groups, trade unions and student movements. Among the leading figures of the opposition was Fidel Castro. He was to become the leader of the Cuban Revolution, a movement that sought to overthrow Batista and end the corruption and oppression of his regime. The rise of Castro and his supporters eventually led to a direct confrontation with Batista's government, marking a decisive turning point in Cuba's history.

Opposition to Fulgencio Batista in Cuba was a mosaic of groups and movements with varying motivations and objectives, each playing a crucial role in the struggle against his authoritarian regime. The Orthodox Party, under the leadership of Eduardo Chibás, was a major political player, attracting many young Cubans through its commitment to open government, anti-corruption and democratic reform. Chibás' charismatic personality was a key element in mobilising popular support. The 26 July Movement, founded by Fidel Castro after the failed attack on the Moncada barracks in 1953, became one of the most emblematic revolutionary groups of the time. Despite the initial imprisonment of Castro and other members, the movement persisted, planning the revolution from exile in Mexico. The Revolutionary Directorate, made up mainly of students, chose the path of direct action to oppose Batista. Their involvement in demonstrations and attacks on the regime's security forces helped intensify the pressure against the dictator. Cuban trade unions also played a key role, using strikes and demonstrations to challenge working conditions and oppose the dictatorship. Their ability to mobilise workers added an important dimension to the resistance. In addition, several left-wing groups advocated radical social and economic reforms, adding to the diversity of the opposition. These diverse groups and movements eventually found common ground in their shared goal of overthrowing the Batista regime, a convergence that played a decisive role in the success of the Cuban Revolution in 1959. After the fall of Batista, under the leadership of Fidel Castro, Cuba underwent radical changes, including the nationalisation of industries and land, the establishment of a socialist government and the development of close relations with the Soviet Union. These transformations profoundly altered Cuba's political, economic and social landscape.

Fidel Castro was undeniably a central figure in the opposition to Fulgencio Batista's dictatorship in Cuba. His political career, which began in the 1940s, was marked by a failed attempt to overthrow Batista in 1953, followed by a period of imprisonment. On his release, Castro went into exile in Mexico, where he founded the 26 July Movement, which was to play a crucial role in the Cuban revolution thanks to its guerrilla warfare against the Batista regime. But the 26th of July Movement was not alone in its struggle. The Orthodox Party, under the leadership of the charismatic Eduardo Chibás, advocated government transparency, the fight against corruption and democratic reforms, rallying many young Cubans to its cause. The Revolutionary Directorate, made up mainly of students, distinguished itself by its commitment to direct action aimed at destabilising the Batista regime, in particular through demonstrations and attacks on government security forces. Cuban trade unions, playing a key role in workers' mobilisation, organised strikes and demonstrations to protest against working conditions and oppose the dictatorship. These trade union movements helped to strengthen the resistance against Batista. In addition, various left-wing groups campaigned for radical social and economic reforms, adding to the diversity and richness of the opposition. The convergence of these diverse forces around the common goal of overthrowing the Batista regime was a decisive factor in the success of the Cuban Revolution of 1959. This union led to the establishment of a new government under the leadership of Fidel Castro, which initiated profound and lasting changes in Cuba.

The Cuban Revolution of 1959, the result of the union of the opposition against the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, marked a turning point in Cuba's history. This revolution brought about profound and lasting transformations in Cuban society, with several major changes. One of the most significant changes was the nationalisation of industry and land. Fidel Castro's revolutionary government took control of key sectors of the economy, including foreign companies. The aim was to reduce the influence of foreign interests on the Cuban economy and redistribute wealth for the benefit of the people. The establishment of a socialist government was also a major change. Castro's regime implemented socialist policies, including free health and education services for all Cubans, and agrarian reforms to redistribute land from large landowners to peasants. The Cuban Revolution also led to the establishment of close ties between Cuba and the Soviet Union. This strategic alliance played an important role in international politics during the Cold War, particularly in bringing Cuba closer to the Communist bloc. This raised concerns and tensions with the United States, greatly influencing international relations and the dynamics of the Cold War.

The period leading up to the Cuban Revolution was marked by a complex relationship between Cuba and the United States. The US government supported Fulgencio Batista's regime economically and militarily, while US companies had invested heavily in the Cuban economy. However, US support for Batista was highly unpopular with the Cuban people, who perceived the US as supporting a brutal, repressive and corrupt dictator. Faced with the rise of the Cuban Revolution in the 1950s, the US government adopted a hostile stance towards the revolutionary movement. The US sought to discredit Fidel Castro and considered plans to eliminate him. However, these attempts did not prevent the revolution from succeeding. In 1959, Batista was overthrown by revolutionary forces led by Castro, marking a major change in Cuban politics. The rise of Castro and the establishment of a socialist government in Cuba had profound implications for relations between Cuba and the United States. This period ushered in an era of tension and antagonism that continued throughout the Cold War, mainly due to Cuba's alignment with the Soviet Union. This dynamic influenced international policies and was a key factor in the complexity of relations between the United States and Cuba during this period.

The landing of Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and their guerrilla group in Cuba in 1956, known as the Granma expedition, was the starting point of their struggle to overthrow the regime of Fulgencio Batista. Although their first attempt was a failure, with a disastrous confrontation shortly after landing decimating much of their group, Castro, Guevara and a few other survivors managed to escape and take refuge in the Sierra Maestra mountains. It was in these mountains that Castro and his companions began waging a guerrilla war against Batista's forces. They used the difficult topography of the region to carry out surprise attacks and adopted effective guerrilla tactics. During this period, Castro succeeded in projecting an image as a social reformer, openly criticising the corruption and abuses of the Batista regime. His calls for social justice and equality resonated with large sections of the Cuban population, helping to increase his popular support. Over time, Castro's revolutionary movement grew in power and influence. The guerrillas' ability to win military victories, as well as their commitment to social reform, attracted more and more Cubans to their cause. This dynamic gradually eroded support for the Batista regime among both the population and the army. In 1959, revolutionary forces finally succeeded in overthrowing Batista's government, bringing about profound and lasting changes in Cuba. Under Castro's leadership, the Cuban Revolution led to the nationalisation of industries and land, the introduction of social and educational reforms, and the establishment of a socialist government. These changes had considerable repercussions, not only in Cuba but also in the wider context of world politics, particularly during the Cold War period.

The CIA's attempts to eliminate Fidel Castro are well documented and are among the most controversial episodes of the Cold War. These plots, which were often extravagant and sometimes far-fetched, included plans to poison Castro, to blow him up with a cigar bomb, and a variety of other methods. There were many reasons for these assassination attempts. The United States saw Castro as a significant threat to its influence in the Western hemisphere, not least because of his links with the Soviet Union. In addition, Castro's nationalisation policies, which affected American companies in Cuba, and his anti-American rhetoric exacerbated tensions. Despite these multiple assassination attempts, Castro survived each one, reinforcing his image as an invincible leader in the face of adversity. His ability to resist CIA plots added to his legend and reinforced his status as a symbol of resistance to American imperialism. Under Castro's leadership, Cuba not only established a socialist regime, but also became a strategic ally of the Soviet Union, playing a key role in the dynamics of the Cold War, particularly during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. The Cuban revolution and the rise of Castro also had a profound impact on Latin America, inspiring other revolutionary and anti-imperialist movements in the region. This helped shape relations between the United States and Latin American countries for many years, often increasing mistrust and tension.

1 January 1959 was a crucial milestone in Cuban and world history. The arrival of Fidel Castro and his revolutionary forces in Havana and the flight of Fulgencio Batista signalled the end of one era and the beginning of another. The success of the Cuban Revolution not only changed the trajectory of Cuba, but also had a profound impact on international politics. The reforms undertaken by Castro were radical and affected every aspect of Cuban society. The nationalisation of industries, particularly the sugar industry, which was vital to the Cuban economy, was a major blow to American interests. Agrarian reform overturned the traditional land structure, redistributing land to the peasants. Investment in education and healthcare has had a lasting positive impact on the standard of living of the Cuban people. The deterioration in relations with the United States was almost inevitable given the direction taken by Castro's government. The trade embargo imposed by the United States was an attempt to put pressure on the Cuban regime, but it pushed Cuba even closer to the Soviet Union. This alliance not only provided Cuba with crucial economic and military support, but also transformed the island into a key theatre of the Cold War. The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, when Soviet missiles were installed on Cuban soil, was one of the most tense moments of the Cold War, bringing the world to the brink of nuclear war. In Latin America, the Cuban Revolution served as an inspiration and model for other left-wing and revolutionary movements. The existence of a socialist state in the Western Hemisphere, so close to the United States, represented a major ideological and strategic challenge for the United States for decades.

The first steps of the revolution

When Fidel Castro arrived in Cuba with his brother Raul and Che Guevara in December 1956, they were initially greeted with scepticism and disbelief by many Cubans. Many doubted that a small group of rebels could succeed in overthrowing the Batista regime. Castro and his supporters took refuge in the mountains of the Sierra Maestra, where they enjoyed the support of local peasants sympathetic to their cause. Over time, Castro and his supporters built up their strength through guerrilla tactics and by winning the support of local communities. They engaged in rapid, mobile attacks against Batista's forces, drawing on their knowledge of the terrain and popular support. Their movement grew, attracting deserters from Batista's army, local volunteers and even sympathisers from other parts of Cuba. At the same time, Batista's regime began to show signs of weakness, with problems of corruption and growing discontent among the population. Castro made effective use of the media to spread his message and attract international attention, helping to strengthen his cause. What began as a seemingly desperate enterprise turned into a revolutionary force capable of overthrowing an established dictator. It was a combination of strategy, popular support, resilience and the ability to inspire and mobilise people around a common vision that enabled Castro and his supporters to succeed where many thought they would fail.

In the tumultuous 1950s in Cuba, while Fidel Castro and his rebels were fighting in the Sierra Maestra, unrest was also growing in urban areas. Many Cubans, dissatisfied with Batista's oppressive and corrupt regime, mobilised to express their discontent. Students, trade unionists, intellectuals and ordinary citizens took part in protests, strikes and other acts of civil disobedience. These urban movements were crucial in eroding Batista's support base and illustrating the national scope of the discontent. Demonstrators used every opportunity to denounce the regime's corruption, violence and repression. Each act of repression by Batista only fuelled more public indignation, creating a vicious circle for the regime. However, it was the guerrilla tactics employed by Castro and his supporters that finally delivered the decisive blow against Batista. Using the mountains as cover, the rebels launched surprise attacks, gradually weakening Batista's forces and extending their influence over vast rural areas. This guerrilla strategy, combined with urban unrest, created a double threat to Batista. As the rebellion grew in strength and credibility, it became a magnet for those seeking change in Cuba. The rebel ranks swelled with new recruits, and their momentum seemed irresistible. Finally, in 1959, faced with widespread opposition and a deteriorating military situation, Batista fled the country, marking the end of his regime and the beginning of a new era for Cuba under the leadership of Castro.

The Cuban revolution reached a decisive turning point in 1958, a crucial year for Fidel Castro and his guerrillas. By this time, the revolutionary movement had significantly strengthened. The rebels, having built up a robust military structure, were now capable of launching bolder, larger-scale operations against Batista's forces. However, it was not just the rebels' growing success that played a role in Batista's downfall. The international context, in particular the attitude of the United States, was also a crucial factor. Initially, the US government had given Batista considerable support, including supplies of arms and other aid. But as the Cuban revolution intensified and the Batista regime became increasingly brutal in its repression, the US began to reassess its position. In March 1958, in a move that marked a U-turn in US policy, the US suspended arms shipments to Cuba. This decision, prompted by growing concerns about human rights abuses by the Batista government, had a major impact on the conflict. Deprived of essential military resources, the Batista regime saw its advantage rapidly eroded. At the same time, guerrilla forces under Castro's leadership continued to grow and extend their hold on Cuban territory. Towards the end of 1958, the rebels orchestrated a series of triumphant military campaigns, critically weakening Batista's forces. This combination of rebel military success and the withdrawal of US support created the ideal conditions for Batista's downfall. On 1 January 1959, Batista left Cuba, leaving the field clear for the rebels led by Fidel Castro, who thus proclaimed the victory of the Cuban revolution, marking the start of a new era for the country.

The ideological trajectory of Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution is inseparable from Marxism-Leninism, although not all the fighters under his leadership necessarily adhered to this doctrine. Castro's inclination towards socialism was the result of various factors. During his years as a militant student in Havana in the 1940s and 1950s, he forged his political convictions. His in-depth study of Marxist theory, coupled with his admiration for the Soviet Union and its then leader, Joseph Stalin, strongly influenced his world view. Even before the triumph of the Cuban revolution, Castro and his allies had drawn up a political programme aimed at establishing a socialist state in Cuba. This programme emphasised radical reforms, including land reform, improved workers' rights and the nationalisation of key industries. After the fall of Batista, this programme was rapidly implemented. Key industries were nationalised and land redistributed to peasants. Cuba also forged close links with the Soviet Union, which became a crucial economic and military support for Castro's government. Over time, Castro's commitment to Marxism-Leninism grew stronger. In 1965, he officially declared that the Cuban revolution was socialist. Castro's relationship with the Soviet Union evolved into a strategic alliance, making him a central figure in the international communist movement. This alliance not only shaped Cuba's domestic politics but also had a major impact on international politics, particularly during the Cold War period.

The victory of the Cuban revolution in January 1959, led by Fidel Castro, marked a turning point in Cuba's history. Although the rebels had not yet drawn up a detailed plan of government, they were guided by fundamental principles and objectives. These goals reflected their aspirations for a transformed Cuba, free from US influence and meeting the basic needs of its people. Immediate priorities included the pursuit of national independence, job creation for the many unemployed, improved living conditions in rural areas, and greater access to education and healthcare. From its very first months in office, the new government set about achieving these goals through a variety of policy initiatives. An ambitious land reform was launched, aimed at expropriating large estates and redistributing land to small farmers and peasants. The aim was to reduce land inequalities and boost agricultural production. At the same time, efforts were made to improve access to healthcare and education, with a particular focus on rural areas, which had often been neglected in the past. However, these reforms have met with obstacles and resistance. Powerful economic interests in both Cuba and the United States perceived these changes as a threat. Despite these challenges, Castro and his allies continued to develop their political programme, gradually moving towards Marxism-Leninism and the idea of establishing a socialist state. This ideological evolution led to more radical reforms and a growing rapprochement with the Soviet Union. Over the years, the Cuban government has consolidated its socialist regime, profoundly marking the history and politics of the island.

The initial programme of the Cuban revolution, when launched by Fidel Castro and his allies, was based on principles such as national independence, social justice and improved living conditions for the Cuban people. These ideals reflected a desire for change and reform, but did not explicitly call for the establishment of a fully developed communist government. Despite these initial intentions, the United States soon became suspicious of the Cuban revolutionary movement. The United States saw the revolution as a possible threat to its interests in the region, and feared that Cuba might become an ally of the Soviet Union or other communist countries. This perception was rooted in Cold War politics, where strategic and ideological interests dominated international relations. Over time, the ideology of the Cuban revolution evolved towards a stronger emphasis on socialism and the establishment of a planned economy. This evolution contributed to intensifying tensions between Cuba and the United States. Faced with the consolidation of the Castro regime and its rapprochement with the Soviet Union, the United States adopted an increasingly hostile stance towards Cuba. It undertook various actions to undermine the Cuban revolution, including attempts at political interference and economic sanctions. These actions were part of a broader policy of US intervention in Latin America during the Cold War. This policy was often motivated not only by fear of communism, but also by the desire to maintain US economic and political dominance in the region. In response to US policies, Cuba strengthened its ties with the Soviet Union and other socialist countries, moving further along the road to socialism and further exacerbating tensions with the United States.

Fidel Castro and his supporters' awareness of the threats posed by the United States and other external forces played a central role in the way they consolidated and protected the Cuban revolution. Aware of what was at stake, they adopted several strategies to safeguard their revolutionary gains. Firstly, strengthening the Cuban army was a priority, enabling the country to be defended against any foreign intervention. This was essential in the context of the Cold War, where international tensions could easily lead to armed conflict. Secondly, establishing close ties with the Soviet Union was a key strategy. This alliance offered Cuba crucial economic, military and diplomatic support, strengthening its position on the international stage and its ability to resist American pressure. Thirdly, fostering a strong sense of nationalism and anti-imperialism among the Cuban population served to unite the people around the revolution. This helped to create a collective national identity and galvanise support for the revolutionary cause. However, Castro's government also adopted an intransigent approach to dissent and internal opposition. Non-tolerance of any challenge to government authority and periodic purges against those perceived as counter-revolutionaries reflected a hard line adopted by the regime. This approach was partly motivated by a sense of urgency and crisis, fuelled by fears of internal subversion or external intervention. Over time, as the revolution became more firmly established, the Cuban government became slightly more tolerant of dissent. Nevertheless, the legacy of the early years of the revolution, characterised by the centralisation of power and the one-party system, continued to strongly influence Cuban politics for many years. This approach has had lasting implications for Cuba's political and social landscape, shaping its evolution to the present day.

The political trajectory of the Cuban revolution, orchestrated by Fidel Castro, is a subject rich in nuance, arousing both admiration and criticism. The methods and achievements of Castro and his government can be assessed from a number of angles, including the creation of coalitions of support and strategies for maintaining power. The creation of coalitions of support was essential at the start of the revolution. The goals of social justice and national independence attracted a wide range of support, resonating with many Cubans who felt marginalised or oppressed under Batista's regime. Anti-imperialism, manifested in opposition to US influence, was also a key factor in consolidating popular support. At the same time, Castro's management of power involved a variety of tactics. Building a cult of personality around his charismatic figure played a crucial role in mobilising the masses and centralising authority. This approach was complemented by purges of dissidents and potential rivals, eliminating challenges to Castro's power. However, this strategy has been criticised for being incompatible with democratic principles. Perspectives on the Cuban revolution are deeply divided. On the one hand, some critics argue that the centralised approach and one-party system have suppressed political pluralism and compromised freedom of expression, as well as the democratic potential of the revolution. On the other hand, defenders of the revolution point to achievements in social justice, education and healthcare, as well as resistance to foreign influence. They consider that the measures taken were necessary in the face of constant external threats.

The alignment of Fidel Castro and his government with the Communist Party of Cuba (CPC) is a complex and controversial subject that continues to be hotly debated. On the one hand, it is true that the CCP had a long history of opposition to the Batista dictatorship and had a solid infrastructure as well as a committed militant base. Castro, who was not originally a communist, saw in aligning himself with the CCP a pragmatic opportunity to consolidate revolutionary power. The alliance provided the revolutionary government with a robust organisational structure and additional ideological legitimacy. Over time, this relationship was strengthened, and communism became the official ideology of the Cuban government, with the CCP as the sole legal political party. On the other hand, some critics of the Cuban revolution see this development as a deviation from the original ideals of the revolution, centred on social justice, independence and anti-imperialism. They argue that the adoption of communism has led to increased centralisation of power and restrictions on political and civil liberties. On the other hand, others argue that this alignment was a strategic necessity, enabling Cuba to resist external pressure, particularly from the United States and other Western powers. They also argue that this alliance has enabled social and economic reforms to be pursued that have benefited many Cubans. Debates about this period in Cuban history are deeply polarised, reflecting divergent perspectives on issues of power, ideology and foreign policy. This polarisation underlines the complexity of Cuban history and the difficulty of reconciling different worldviews on the legacy of the Cuban revolution.

Fidel Castro's triumphant march from Santiago de Cuba to Havana in January 1959 was a pivotal moment in Cuban history, crucial in mobilising and rallying the Cuban people to the revolutionary cause. As they crossed the island, Castro and his supporters aroused a wave of popular enthusiasm, with huge crowds greeting them as heroes. This event played a fundamental role in building support for the new government and establishing Castro's legitimacy as a national leader. During the march, Castro skilfully used speeches and public meetings to communicate his vision of a renewed Cuba, based on values of social justice, independence and opposition to imperialism. He articulated a programme that sought to address the concerns and aspirations of Cubans, particularly the working classes and rural populations, who had long been neglected or oppressed under the Batista dictatorship. In the months that followed, Castro's government stepped up its efforts to mobilise popular support, organising mass rallies, encouraging grassroots organisation and promoting a cult of personality around Castro. These strategies were effective in consolidating widespread support, particularly among those who had most to gain from the reforms promised by the revolution. The Castro March was therefore much more than a simple celebration of victory: it was a decisive moment for establishing the authority of the new government, creating a sense of national unity and channelling popular energy into building a new Cuba. This period laid the foundations for what was to become a radical transformation of Cuban society and the economy under Castro's leadership.

Creation or restructuring of mass organisations (1959-1961)

Fidel Castro's skilful use of the media after the triumph of the revolution in 1959 was a key component of his strategy to consolidate power and mobilise popular support for his government. Television and radio, in particular, served as essential platforms for spreading the revolutionary message and reaching a wide audience across Cuba. Castro's speeches, often long and impassioned, were broadcast regularly on television and radio. In these speeches, he positioned himself as a charismatic leader and a dedicated servant of the interests of the Cuban people. He played on themes such as patriotism, national pride and the hope of a better life, presenting the revolution and its government programme as the path to achieving these aspirations. Castro's populist approach, combined with his oratorical talent and ability to communicate effectively via the media, was crucial in forging broad popular support. His speeches did not simply convey information; they were designed to arouse emotions, inspire and mobilise citizens around a common project. By positioning himself as the defender of Cuban sovereignty and the champion of the people's aspirations, Castro was able to tap into feelings deeply rooted in Cuban society. His ability to rally citizens to the cause of his government played a fundamental role in building a sense of national unity and maintaining the legitimacy of his regime in the years following the revolution. Castro and his government's mastery of the media not only helped spread the revolutionary message, but also shaped public opinion and strengthened cohesion around the vision and objectives of the Cuban revolution.