拉丁美洲国家的独立

根据 Aline Helg 的演讲改编[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

美洲独立前夕 ● 美国的独立 ● 美国宪法和 19 世纪早期社会 ● 海地革命及其对美洲的影响 ● 拉丁美洲国家的独立 ● 1850年前后的拉丁美洲:社会、经济、政策 ● 1850年前后的美国南北部:移民与奴隶制 ● 美国内战和重建:1861-1877 年 ● 美国(重建):1877 - 1900年 ● 拉丁美洲的秩序与进步:1875 - 1910年 ● 墨西哥革命:1910 - 1940年 ● 20世纪20年代的美国社会 ● 大萧条与新政:1929 - 1940年 ● 从大棒政策到睦邻政策 ● 政变与拉丁美洲的民粹主义 ● 美国与第二次世界大战 ● 第二次世界大战期间的拉丁美洲 ● 美国战后社会:冷战与富裕社会 ● 拉丁美洲冷战与古巴革命 ● 美国的民权运动

拉丁美洲国家的独立是一个复杂、多层面过程的一部分,与 19 世纪初的全球动荡密切相关。受殖民社会内部紧张局势以及美国革命和海地奴隶起义等外部事件的影响,这些争取独立的斗争受到各种力量的影响和刺激。殖民地与其欧洲大都市(尤其是西班牙和葡萄牙)之间联系的削弱或瓦解在促进这些运动方面发挥了至关重要的作用。拿破仑战争在欧洲造成的混乱使殖民帝国不堪一击,忙于应付内部矛盾,造成了独立运动试图填补的政治真空。

法国大革命尤其产生了重大影响,成为拉丁美洲独立愿望的催化剂。自由、平等和博爱的革命思想在拉美精英和知识分子中产生了深刻的共鸣,激励他们在自己的土地上追求更加公正、公平的社会和政治秩序。法国大革命不仅仅是一种激励,它还削弱了因内部斗争而四分五裂的欧洲殖民国家的力量,为殖民地争取独立铺平了道路。

除了这些欧洲的影响,革命思想和运动的传播也助长了动荡和变革的气氛。思想和政治哲学的交易跨越国界,将看似不同的独立运动团结在一个共同的目标之下:自决和摆脱殖民统治。拉美国家的独立是内部和外部力量共同作用的结果,受到当时历史和地缘政治环境的影响。这创造了一个充满活力和变革的时期,不仅重新定义了拉丁美洲的政治疆界,还留下了影响该地区至今的持久遗产。

外部原因

19 世纪初拿破仑入侵伊比利亚半岛是拉丁美洲国家独立运动的决定性转折点。通过占领西班牙和葡萄牙,拿破仑在欧洲制造了一场重大的政治危机,直接影响到海外殖民地。由于西班牙国王被迫退位和葡萄牙政局不稳,这些欧洲大都市缺乏一个强有力的中央政权,这在殖民地造成了权力真空。地方治理机构以前因传统忠诚而与王室紧密相连,现在突然发现自己没有了明确的指导或无可置疑的合法性。这为西蒙-玻利瓦尔、何塞-德-圣马丁等富有魅力和影响力的地方领导人打开了大门,他们抓住机会要求各自的领土独立。在自由和国家主权理想的驱使下,这些领导人也受到了当时革命原则的鼓舞。反对殖民统治的起义不仅仅是一种政治反抗行为。它也是社会和经济改革大背景的一部分,旨在打破殖民压迫的枷锁,建立新的民族身份。拿破仑入侵伊比利亚半岛引发了一连串事件,导致整个拉丁美洲出现独立浪潮。这是一个深刻变革的时期,独立英雄们娴熟地驾驭着不断变化的政治格局,建立了新的国家,并在该地区的历史上留下了影响深远的遗产。

1808 年拿破仑入侵伊比利亚半岛,标志着拉丁美洲独立史上的一个关键时刻。随后,费迪南德七世国王被法国人俘虏,他的缺席严重破坏了西班牙殖民地统治者与被统治者之间的传统权力格局,引发了半岛战争,造成了政治真空。在这种不确定的气氛中,西蒙-玻利瓦尔等地方领导人得以抓住机会接管政权,维护自己的权威。当时的西班牙政府软弱无力,忙于应付欧洲的冲突,因此得以争取支持并动员当地民众支持独立。在法国大革命和其他当代革命理想的激励下,人们对自由和自治的渴望日益高涨,从而推动了这些运动的发展。巴西的情况则不同,1808 年,葡萄牙王室及其宫廷为躲避拿破仑的入侵,逃往里约热内卢。葡萄牙政府所在地的迁移有助于加强巴西的身份认同,使王室权力更接近殖民地。1822 年,王储多姆-佩德罗(Dom Pedro)宣布独立,成为巴西皇帝。拿破仑的入侵以及随后西班牙和葡萄牙传统势力的瓦解,为拉丁美洲殖民地的独立创造了独特的机遇。这些事件引发了一系列复杂、相互关联的运动,塑造了该地区的历史,并导致了独立国家的出现,每个国家都有自己的道路和对主权的挑战。

拉丁美洲殖民地复杂的人口构成在该地区的独立运动中发挥了重要作用。在这些殖民社会中,大量土著人口和奴隶往往被边缘化,被西班牙和葡萄牙殖民者视为二等公民。这种等级森严的结构使欧洲后裔享有特权,而土著和非洲群体则处于不利地位,导致不满情绪和紧张关系日益加剧。社会和经济不平等加剧,为动乱和反抗创造了肥沃的土壤。一些独立运动提出了为这些受压迫群体争取更好的代表权和公平权利的要求,尽管在独立后时期这些目标的实现往往受到限制。此外,启蒙运动的自由、平等和自治理想也对拉丁美洲的独立运动产生了深远影响。孟德斯鸠、卢梭和伏尔泰等哲学家的著作引起了该地区受过教育的精英的共鸣,他们从这些原则中看到了一个更公平、更民主的社会模式。启蒙思想帮助形成了一种超越殖民地界限的解放话语,为质疑君主权威和殖民统治的合法性提供了思想基础。这些理想与当地的不满情绪和社会经济条件相结合,形成了一股强大的动力,导致许多拉丁美洲国家的独立。拉丁美洲争取独立的斗争是一个复杂而多面的过程,受到内部和外部因素的影响。该地区独特的人口构成、对土著居民和奴隶的压迫以及启蒙运动理想的影响汇聚在一起,形成了一幅丰富而微妙的织锦,最终产生了独立的主权国家。

巴西的独立

巴西的独立是拉丁美洲非殖民化历史上独特而精彩的篇章,这主要归功于 1808 年葡萄牙宫廷迁往里约热内卢。面对拿破仑进军欧洲,葡萄牙摄政王若昂六世担心葡萄牙遭到入侵,于是策划了一场史无前例的大规模王室迁移。包括王室成员、政府官员和大量财富在内的 10,000 至 15,000 人在英国人的护送下登船前往巴西。这一事件被称为 "葡萄牙宫廷的转移",对殖民地产生了直接而深远的影响。宫廷的到来将里约热内卢变成了一个行政和文化中心,刺激了贸易和经济活动,并引入了新的社会和政治规范。巴西从一个殖民地变成了一个与葡萄牙联合的王国,迎来了前所未有的自治时期。这一新动态为相对和平地过渡到独立铺平了道路。1822 年,若昂六世之子、王位继承人佩德罗王子宣布巴西脱离葡萄牙独立。这一大胆的举动被称为 "伊皮兰加的呐喊",是始于葡萄牙宫廷到来的进程的顶点。佩德罗王子加冕成为巴西第一位皇帝,标志着一个独立主权国家的诞生。巴西的独立不同于拉丁美洲的其他独立运动,它的冲突性较小,而且具有王朝的连续性。巴西没有与大都市暴力决裂,而是走了一条更加微妙和合作的独立之路,这既反映了殖民地的独特情况,也反映了皇室存在的持久影响。

从 1808 年到 1821 年,巴西的政治和文化面貌发生了翻天覆地的变化,王室和葡萄牙政府官员纷纷迁往里约热内卢,以躲避欧洲的拿破仑战争。在此期间,巴西不再仅仅是殖民地,而是葡萄牙帝国的中心。这种地位上的变化刺激了前所未有的经济和文化增长。港口向国际贸易开放,教育和文化机构得以建立,基础设施得到发展。此外,殖民地的精英阶层开始享有更大的影响力,并形成了自主意识和新生的民族主义。然而,这一解放进程也并非没有矛盾。直到 1821 年,葡萄牙国王若昂六世认为葡萄牙已经足够稳定,决定返回里斯本。他留下儿子佩德罗统治巴西。这一决定挑起了不和,加剧了巴西精英与葡萄牙官员之间的紧张关系,前者希望保留甚至扩大自治权,后者则希望恢复对殖民地的控制。局势变得越来越紧张,要求独立的呼声也越来越高。最终,1822 年,佩德罗对巴西精英的要求和日益增长的自决愿望做出了回应。他宣布巴西独立,结束了葡萄牙长达三个多世纪的统治。他加冕成为巴西第一位皇帝,开创了巴西的新纪元。巴西的独立以其相对和平的性质和在拉丁美洲的独特性而著称。它不是一场暴力革命,而是一个渐进的赋权和谈判过程的结果,王室在巴西的存在和独特民族身份的出现等因素都促进了这一过程。葡萄牙宫廷迁往巴西不仅改变了殖民地的动态,还为向独立过渡奠定了基础,这在拉丁美洲历史上仍具有里程碑意义。

在葡萄牙宫廷驻扎里约热内卢期间,巴西精英享有更大的自主权和影响力,他们不愿回到 1808 年之前的从属地位。他们意识到了历史机遇,说服佩德罗一世留在巴西,成为这个新生国家的独立皇帝。1822 年,他响应了他们的号召,宣布巴西脱离葡萄牙独立,建立了第一个巴西帝国。然而,这一独立宣言并不意味着与过去的彻底决裂。巴西仍然是一个奴隶君主制国家,殖民地的社会和经济结构在很大程度上保持不变。策划独立的精英阶层继续掌权,而包括被奴役的非洲人在内的大多数人仍然被边缘化和压迫。事实上,奴隶制在巴西仍然合法,并一直持续到 1888 年被废除。巴西历史上的这一悲剧凸显了巴西独立的复杂性。虽然独立是朝着国家主权迈出的重要一步,但它并没有给国家的社会或经济结构带来任何深刻的变化。经过漫长而复杂的过程,废除奴隶制的斗争最终于 1888 年取得成功,这揭示了新独立的巴西民族所面临的矛盾和挑战。独立使巴西摆脱了殖民统治,但奴隶制的枷锁及其所象征的不平等仍牢牢地保留了几代人。巴西迈向一个更加公平和包容的社会的道路是曲折的,这既说明了独立的承诺,也说明了独立的局限性。宣布独立只是社会和政治变革进程的开端,这一进程将持续到佩德罗一世时代之后,反映了殖民遗留问题的复杂性和拉丁美洲不平等现象的长期存在。

西属美洲大陆:从效忠国王到内战(1810-1814 年)

1810 年,拿破仑战争和西班牙君主制的动荡导致欧洲局势动荡,随之而来的是西班牙美洲殖民地的革命运动浪潮。当地领导人注意到马德里没有一个强有力的中央政府所留下的权力真空,抓住机会重新定义了他们与大都市的关系。这些运动起初是微妙而谨慎的,重点是保持对西班牙国王斐迪南七世的忠诚,维护现有的殖民制度。他们的动机是希望得到保护,免受殖民官员可能的滥用职权,而不是希望与西班牙彻底决裂。但是,随着西班牙和法国之间的战争一拖再拖,欧洲政局持续动荡,拉丁美洲的许多领导人开始呼吁实现更大的自治。启蒙运动的理想主义、美国革命的榜样,以及对不公平的殖民制度日益增长的挫败感,激发了人们对独立的渴望。对遥远国王的忠诚,以及牺牲殖民地利益而有利于大都市的制度开始瓦解。自由、平等和主权的理念引起了克里奥尔人和其他地方精英的共鸣,他们将独立视为按照更加公正和民主的路线重塑社会的机会。因此,欧洲的局势引发了一个革命进程,随着时间的推移,从保守地维护殖民秩序发展到激进地要求自治和独立。拉丁美洲的独立运动深深植根于当地环境,但也受到全球事件和思想的影响,这说明了 19 世纪初争取自由和主权的斗争的复杂性和相互关联性。

1814 年,拉丁美洲西班牙殖民地一触即发的动乱爆发为公开内战。不同派别为争夺对不同殖民地的控制权,结成了复杂多变的联盟。他们的目标各不相同,有时甚至相互冲突。一些势力受到法国和美国革命共和理想的启发,试图建立独立的共和国。他们渴望与过去的殖民地彻底决裂,建立更加民主和公平的治理体系。其他派别通常由保守派和保皇派组成,他们试图重建对西班牙国王的忠诚,担心独立会导致无政府状态,破坏既定的社会秩序。对他们来说,对王室的忠诚是稳定和连续性的保证。最后,还有一些人设想建立新的帝国或自治政权,试图调和对自由的渴望与对强大的中央集权政府的需求。这些独立战争的特点是冲突激烈,往往十分残酷,反映了殖民社会内部根深蒂固的紧张关系。战争遍及整个大陆,从安第斯高原到拉普拉塔河平原。随着冲突的发展,西班牙在美洲的势力逐渐削弱。通常由西蒙-玻利瓦尔和何塞-德-圣马丁等魅力人物领导的独立势力的胜利,导致了西班牙帝国在美洲的解体。到 1825 年战争结束时,各个独立国家的出现重新定义了拉丁美洲的政治版图。每个新国家都面临着各自的建国挑战,殖民遗留问题、社会分裂和相互冲突的愿望将在未来几十年继续影响着该地区。独立之路漫长而艰辛,建国进程才刚刚开始。

最初,1808 年拿破仑入侵西班牙期间,费迪南七世国王被废黜,美洲的西班牙殖民地出现了权力真空。为此,整个城镇和地区都成立了地方议会,在国王不在时进行管理。这些议会声称代表君主行事,援引了一项被称为 "退出规则 "的法律原则,即在合法君主缺席的情况下,主权归还给人民。这些军政府虽然忠于王室,但开始实行自主治理,在等待国王回归的同时努力维持秩序和稳定。他们的存在是基于这样一种信念,即一旦欧洲局势得到解决,国王就会归来并重新掌权。然而,随着西班牙和法国之间的战争一拖再拖,西班牙的政治局势变得越来越混乱,国王显然不会在短时间内返回。在这种不确定的背景下,许多地方领导人开始重新评估他们对遥远而衰弱的王室的忠诚。要求更大自治权,甚至完全脱离西班牙统治的呼声开始高涨。当时流行的自由和平等的理想引起了该地区知识精英和政治领袖的共鸣,他们认为独立是按照更加现代、民主的路线重新定义社会的机会。这些革命运动的兴起并非千篇一律,每个地区都有自己的动力和主要参与者。然而,总的趋势是明确的:对西班牙王室的效忠正在减弱,要求自治和独立的呼声日益高涨。在这一过渡时期,旧的忠诚开始让位于新的愿望,这为后来在整个拉丁美洲爆发的独立战争奠定了基础。这一进程的起点是在国王不在的情况下维持秩序的临时努力,后来转变为对殖民制度的激烈挑战以及对自由和自决的热情追求。

费迪南德七世于 1808 年退位后,西班牙在美洲殖民地组建的地方军政府主要由殖民地精英组成。这些军政府的成员通常来自地主和商人阶层,包括半岛人(在西班牙出生的人)和克里奥尔人(原籍西班牙但在殖民地出生的人)。半岛人通常在殖民地政府中担任要职,他们一般更忠于西班牙和殖民地权力机构。克里奥尔人虽然也与西班牙文化和传统有着密切联系,但有时对当地的需求和特殊性更为敏感,他们常常因被排除在中半岛人的最高权力职位之外而感到沮丧。地方议会成立的明确目的是在国王缺席时以国王的名义维持秩序和进行管理。他们最初并不是要挑战王权,而是要在危机和不确定时期维护王权。由于殖民地社会的复杂性,军政府成员的利益和动机可能各不相同,半岛人和克里奥尔人之间的紧张关系有时会在这些管理机构内部造成分裂。随着西班牙局势的恶化和国王回国前景的暗淡,地方议会变得越来越自主,要求自治和独立的呼声开始出现,尤其是在克里奥尔人中。这些军政府的形成和由此产生的动力是最终导致西班牙拉丁美洲独立运动的关键因素。

随着拿破仑军队占领西班牙大部分地区,加的斯军政府成为抵抗运动的中心和自封的管理机构。它旨在代表整个西班牙帝国,协调对拿破仑的战争。然而,当时的情况十分复杂。在殖民地就地成立的美洲军政府有自己的关切和利益,由于距离遥远、沟通受限和利益分歧,与加的斯军政府的协调十分困难。加的斯军政府还采取了一项重要举措,即在 1810 年至 1812 年期间召开制宪会议 Cortes de Cadiz。这一事件促成了 1812 年《加的斯宪法》的起草,这是一部自由、进步的宪法,旨在实现西班牙的现代化,并为殖民地带来改革。然而,这些改革的实施非常复杂,殖民地的反应也各不相同。一些殖民地将改革视为机遇,而另一些殖民地则对他们的代表方式感到不满。一些克里奥尔人感到沮丧的是,宪法似乎将大都市的利益放在首位,而牺牲了殖民地的利益。这些紧张局势助长了西班牙美洲殖民地的独立运动,因为加的斯军政府和科尔特斯的合法性和权威在当地受到了挑战。

加的斯最高中央军政府,以及后来于 1810 年接管政权的摄政委员会,在对拿破仑的战争中寻求美洲殖民地的支持。他们承认美洲各省与伊比利亚半岛各省之间的平等原则,是争取这种支持的一种方式。殖民地参与帝国政府的设想是通过加的斯议会来实现的,议会中包括来自殖民地的代表。这次会议产生的《1812 年加的斯宪法》也承认了殖民地的权利,并确立了代表权和平等的原则。然而,这些原则的实施面临着挑战。距离和通讯的限制使殖民地的有效代表权变得复杂,不同群体之间也存在紧张关系和利益分歧。例如,一些克里奥尔人对代表他们的方式和考虑他们利益的方式感到不满。这些紧张关系导致了殖民地的不稳定和不满,最终助长了独立运动。西班牙的政治危机,加上新出现的民族主义和主权观念,导致美洲殖民地对西班牙权威的质疑与日俱增,对自治和独立的渴望与日俱增。

召开代表整个帝国(包括西班牙各省、美洲甚至亚洲的菲律宾)的大会,是对法国入侵伊比利亚半岛所造成危机的回应。这一尝试旨在为国王斐迪南七世缺席时的临时政府营造一种统一感和合法性。然而,这一计划的实施受到了各种障碍的阻碍。美洲殖民地地处偏远,当时的通讯条件有限,因此很难协调和执行西班牙做出的决定。此外,殖民地和本土利益之间的紧张关系,以及各地区代表之间的观点分歧,也使得达成共识的努力变得更加复杂。1810-1812 年加的斯议会的召开是帝国代表制思想的具体体现,但也遇到了类似的挑战。由于殖民地的许多人已经开始质疑西班牙的权威,大都会重新控制殖民地的企图往往遭到怀疑和抵制。对西班牙统治的不满、启蒙思想的影响以及当地精英对更大自治权和控制权的渴望等多种因素推动了殖民地开始出现的独立运动。西班牙的混乱局势为这些运动提供了机会,加的斯中央最高军政府试图维持对帝国的控制,但最终被证明不足以遏制这些力量。

加的斯议会的代表权问题是一个重大问题,也是大都会与殖民地之间的摩擦点。西班牙担心,如果殖民地按照人口比例获得代表权,就会失去对议会决策的控制权。摄政委员会决定减少殖民地的代表人数,以保持平衡,维护大都市的优势地位。这一决定违背了平等和公平代表的原则,而这些原则正是召开大会的理由。殖民地的许多领导人和知识分子认为这是对都城承诺的背叛,也助长了西班牙不公平对待殖民地或不尊重殖民地的情绪。殖民地在议会中的代表权不足加剧了现有的不满情绪,并在许多地区强化了独立的理由。这也加剧了殖民地内不同社会和经济群体之间的分歧,因为每个群体都在寻求保护和促进自身的利益。最终,关于科尔特斯代表权的决定成为了一个典型的例子,说明了大都市管理和控制殖民地的企图是如何与美洲许多人的愿望和期望脱节的。它加速了独立运动,削弱了大都会对其广袤海外领土的合法性和权威。

殖民地社会的许多阶层,尤其是克里奥尔精英阶层,对大都市的不公正感和不满情绪与日俱增,他们感到自己被西班牙边缘化并受到蔑视。出生在殖民地但拥有欧洲血统的克里奥尔人往往在殖民地担任要职并具有影响力,但他们仍然觉得自己被大都市视为二等公民。加的斯议会中殖民地代表人数不足的决定只会加剧这种感觉。启蒙思想的影响、人权和国家主权概念的传播,以及从美国和法国革命中汲取的灵感,也对独立愿望的形成起到了推波助澜的作用。在这些因素的共同作用下,出现了寻求打破殖民地关系、建立主权独立国家的革命运动。由此引发的独立战争错综复杂,往往充满暴力,涉及各种派别和利益,并持续多年。最终的结果是西班牙帝国在美洲解体,出现了一系列独立国家,每个国家都有自己的挑战和机遇。这一时期留下的影响至今仍在影响着拉丁美洲的政治、社会和文化。

拉丁美洲的独立战争是由复杂的经济、社会和政治因素共同作用形成的。克里奥尔精英,即出生在殖民地的欧洲裔公民,往往在当地很有影响力,但却感到受到西班牙当局的蔑视。在加的斯议会中的代表权不足加剧了这种不满情绪,在克里奥尔人的心目中,西班牙并不认为他们是平等的。这一时期的另一个特点是,自治的愿望日益强烈,自由主义思想在拉丁美洲的影响越来越大。殖民地希望获得更大的自治权,在帝国管理中拥有更多的发言权。在议会中的低代表权被认为是对这些权利的剥夺,这与自由、平等和国家主权的理想相冲突,而这些理想受启蒙运动以及北美和法国革命的影响正日益深入人心。当时的地缘政治形势也起到了关键作用。拿破仑对西班牙的占领和西班牙政府的脆弱造成了权力真空,为独立运动提供了机会。西班牙与殖民地之间的距离遥远、通信困难,使得协调和维持控制变得十分困难,从而加剧了这种局面。与此同时,经济和社会紧张局势也加剧了不满情绪。议会中代表不足是殖民地内部不平等和不满情绪等深层问题的表现。不同社会阶层和种族群体之间的冲突反映了僵化的社会和经济结构,即精英阶层掌握权力,而大多数人仍被边缘化。关于科尔特斯代表权的决定是不公正和紧张关系大背景下的催化剂,导致了西班牙帝国在美洲的崩溃。代表权不足凸显了殖民地内部根深蒂固的挫折感和不断变化的愿望,引发了一系列运动,最终导致了新的独立国家的诞生。通往独立的道路是复杂而多因素的,而在议会中的代表权只是塑造拉丁美洲历史上这一关键时期的拼图之一。

西班牙被拿破仑军队占领,国王斐迪南七世被囚禁,在这样一个危机四伏的时期,1812 年宪法(又称《加的斯宪法》)应运而生。这部宪法标志着西班牙及其殖民地政治史上的一个转折点,它建立了议会君主制,削弱了国王的权力,使其更倾向于议会,并旨在实现帝国的现代化。此外,它还寻求行政权力下放,并保障男性普选权,取消了财产或识字要求。这部宪法在美洲殖民地的应用是矛盾的主要焦点。克里奥尔精英认为该文件不足以满足他们对更大自治权和公平代表权的渴望,殖民地在科尔特斯的代表权不足继续引起他们的不满。虽然《加的斯宪法》的寿命相对较短,在斐迪南七世于 1814 年重新掌权后就中止了,但它的影响却经久不衰,成为拉丁美洲新独立国家几部宪法的范本,并为西班牙未来的宪法辩论奠定了基础。它代表了西班牙向更加民主和自由的政府过渡的重要一步,但改革者与保守派之间、大都会与殖民地之间的紧张关系反映了在一个快速变化的帝国中治理所面临的复杂挑战。

1812 年宪法》是西班牙政治史上的一个重要里程碑,它建立了一个自由民主的框架,旨在赋予人民更多的政治权利和代表权。然而,这一重大进步在美洲殖民地并不受欢迎,代表权问题在那里造成了严重分歧。海外领地在议会中的代表权严重不足,这激起了人们的不满,他们认为《宪法》是殖民政策的延续,而殖民政策正是独立运动的推手。更重要的是,宪法从未在殖民地真正实施,因为那里的革命运动已经深入发展,独立的势头过于强劲。因此,虽然《1812 年宪法》标志着西班牙的进步,但它的出台为时已晚,无法缓解殖民地的紧张局势,殖民地认为它与当地的现实和愿望脱节,未能对独立进程产生重大影响。

1812 年宪法》虽然在许多方面有所进步,但仍然反映了当时的种族和民族偏见与分歧。它虽然赋予所有成年男性选举权,但却将这一权利限制在西班牙人、印第安人和西班牙人的混血儿身上。这一限制事实上排除了非洲裔自由人(即非裔拉美人)以及不符合 "血统纯正 "标准(即要求纯西班牙血统)的混血人。这种排斥反映了西班牙殖民地根深蒂固的社会和种族等级制度。非裔拉丁美洲人和某些混血群体常常发现自己被边缘化,并被剥夺了政治和社会权利。尽管《宪法》具有自由主义的愿望,但它未能彻底打破这些障碍,提供真正的普遍平等。有限的选举权是更广泛的种族和社会紧张关系的一种表现,这种紧张关系在独立战争之后长期存在,并继续影响着拉丁美洲的历史和社会。

将非裔拉美人排除在政治权利和代表权之外是 1812 年《宪法》的一大缺陷,而这一疏忽并非无关紧要,因为他们在许多美洲殖民地的人口中占了很大一部分。这种排斥只会使西班牙帝国现有的种族等级制度和对有色人种的歧视永久化和合法化。它违背了《宪法》起草过程中激发的平等和民主理想,阻碍了许多人充分行使其公民权。1812 年宪法》将非裔拉美人排除在外不仅仅是一个简单的疏忽,它还表明了当时西班牙帝国存在的深刻的种族和社会分歧。它提醒人们,改革和现代化的努力仍然受到根植于殖民社会的偏见和不平等的限制,它留下的复杂遗产继续影响着当代拉丁美洲的种族关系和国家建设。

1812 年《宪法》规定,非裔拉美人及其他种族和社会群体被排除在政治权利和代表权之外,这无疑加剧了美洲殖民地的紧张局势和不满情绪。对这些法律和社会不平等的不满与克里奥尔精英对自治和独立的渴望相结合,导致民族主义和革命情绪的沸腾。西班牙在美洲殖民地爆发的独立战争是复杂和多因素的。它们并非简单的政治分歧或不同派别之间竞争的产物,而是表达了对正义和平等的强烈不满和追求。有色人种,尤其是非裔拉美人,在这些斗争中发挥了至关重要的作用,他们往往与克里奥尔精英一起为自由和公民权利而战。然而,即使在独立之后,种族歧视和边缘化的遗留问题依然存在,在许多新独立的国家,所有居民的平等权利和正式公民身份远未实现。独立战争期间表达的自由和平等的理想往往被持续存在的不平等和分裂的现实所背叛,这反映了从殖民帝国向民族共和国过渡的复杂性和矛盾性。

1812 年宪法的实施和摄政委员会的行动造成了美洲各省之间的严重分裂。尽管《宪法》被视为旨在统一帝国的现代自由改革,但其实际应用却远非和谐。一些省份,尤其是克里奥尔精英更倾向于与西班牙政府合作的省份,承认了科尔特斯和摄政委员会的权威。这些地区可能希望新宪法能在帝国内部带来改革和更大的自治权。然而,其他省份则拒绝接受宪法和摄政委员会的权威。拒绝的原因多种多样,但通常包括认为宪法没有充分满足地方自治和独立的要求。殖民地在议会中的代表性不足,非洲裔拉美人等重要群体被排除在政治权利之外,这些都加剧了不满情绪。各省之间的分裂不仅造成了政治紧张局势,还凸显了西班牙帝国的潜在裂痕和矛盾。美洲各省的不同利益和愿望揭示了帝国统一的脆弱性,并提出了帝国能否以现有形式存在下去的根本问题。最终,这些分歧和矛盾削弱了帝国在美洲的权威,为最终导致西班牙帝国在该地区解体的独立运动铺平了道路。尽管《1812 年宪法》具有改良主义的意图,但它未能统一帝国或缓解紧张局势,反而成为了帝国对广袤而多样的领土保持控制所面临的挑战和失败的象征。

在西班牙帝国政治危机和权力斗争的背景下,摄政委员会试图通过任命新的总督来加强对美洲各省的控制。这些任命的目的是取代现有的地方军政府,这些军政府是在国王缺席期间以国王的名义组建的,往往有自己的政治野心。然而,事实证明这一策略在许多省份都存在问题。新的省长往往被视为外来强加的,并不为当地民众所接受。尤其是克里奥尔精英,他们认为这些任命侵犯了他们的自治权,也是对现有军政府合法性的蔑视。在许多情况下,军政府公开拒绝承认被任命的总督的权威,坚持他们有权以国王的名义进行统治。任命的总督和现有的军政府之间随之而来的权力斗争加剧了殖民地的政治紧张局势。在某些情况下,这导致了公开的冲突和叛乱,加剧了整个帝国的不稳定和政治分裂。摄政委员会试图消除军政府的影响并巩固帝国权力,却在不知不觉中扩大了帝国当局与殖民地地方精英之间的差距。军政府对任命的抵制及其保持自治的决心揭示了不满情绪的深度和帝国所面临挑战的复杂性。被任命的总督和地方军政府之间的斗争不仅仅是权力斗争,它还象征着在一个快速转型的帝国中,自治的愿望和维持中央控制的努力之间更广泛的紧张关系。事实证明,这种紧张关系是帝国权威崩溃和独立运动兴起的关键因素,最终重塑了拉丁美洲的政治格局。

摄政委员会任命的总督不被接受,美洲各省之间分歧严重,这在帝国内部造成了不稳定和不信任的气氛。这种局面使摄政委员会对广袤的殖民地保持控制和权威的努力变得更加复杂。各省非但没有统一应对政治挑战,反而越来越专注于自己的内部矛盾,导致整个帝国四分五裂,缺乏凝聚力。更重要的是,这种分裂削弱了摄政委员会协调反拿破仑解放战争的能力。在西班牙最需要协调统一的对策时,帝国却在内部冲突和地区竞争中挣扎。本可用于对抗法国占领的资源被浪费在了内部争斗上,发动一场有效战争的能力受到了阻碍。摄政委员会权威的削弱和美洲各省之间的分裂也为殖民地独立运动的加速铺平了道路。人们感到帝国并不代表当地的利益,而摄政委员会又无法有效地维持秩序和协调治理,这激起了越来越多的不满和变革的愿望。最终,这一时期出现的问题暴露了西班牙帝国模式的局限性和矛盾。在战争和政治急剧变化的背景下,要维持对如此庞大和多样化的帝国的控制,暴露出帝国结构的根本性裂缝。这些裂缝最终导致了帝国的崩溃和拉丁美洲政治格局的彻底重组。

这种分裂以及美洲各省之间缺乏统一的努力,为革命运动的发展和支持创造了有利环境。由于缺乏强大、统一的中央政权,各省之间的关系持续紧张,这为革命运动的发展和取得胜利开辟了空间。革命运动利用了这一分裂局面,在那些感到被中央政权忽视或边缘化的省份和地区找到了盟友。内部矛盾和竞争也为独立运动提供了更大的活动空间,它们往往在各个省份的利益之间相互博弈。随着这些运动势头的增强,他们开始阐述另一种治理和社会愿景,这些愿景通常受到欧洲和北美启蒙运动和革命理想的启发。这些思想引起了殖民地许多人的共鸣,他们渴望变革,渴望打破看似不公正和过时的制度。简而言之,美洲各省之间的分裂和缺乏协调不仅削弱了西班牙对其殖民地的权威,也助长了革命运动的兴起。这些运动最终促成了独立战争,不可逆转地改变了拉丁美洲的政治格局,结束了西班牙长达三个世纪的殖民统治。

地方军政府最初是为了在国王缺席时代表国王进行管理而成立的,是西班牙在美洲的许多殖民地向独立过渡的关键因素。随着西班牙局势的日益混乱和帝国控制力的减弱,这些军政府开始要求更大的自治权。当摄政委员会试图任命新的总督来平定这些地方军政府时,这往往被视为对地方自治的侵犯和破坏。在许多情况下,地方军政府宣布摄政委员会不合法,并拒绝承认新总督的权力。他们声称,在国王不在的情况下,只有他们才拥有合法的管理权。这种权威和合法性的主张是迈向独立的重要一步。这些军政府开始将自己视为主权实体,有权决定自己的命运,而不再是简单地进行管理,等待国王归来。在这种情况下,向自治和自我管理转变是合乎逻辑的一步,在许多情况下,这些军政府是宣布独立的催化剂。这些发展受到当地、地区和国际因素的复杂影响,包括启蒙运动的理想、欧洲和北美的革命以及殖民地内部的经济和社会紧张局势。地方军政府从效忠国王到宣布独立,反映了西班牙美洲政治和社会的深刻变革,为独立战争后出现的独立国家奠定了基础。

然而,并非所有的地方议会都走上了自治和独立的道路。有些人仍然忠于摄政委员会,承认其权威。这些忠诚的军政府通常由保守的精英领导,他们将摄政委员会视为西班牙的合法政府。对他们来说,效忠摄政委员会是恢复帝国秩序和稳定的最大希望。这些精英担心,要求独立和自治的骚动会进一步破坏该地区的稳定,引发社会和经济冲突。此外,他们的经济和社会利益可能与维持现有的殖民秩序密切相关,他们可能会将自治视为对其地位和影响力的威胁。忠诚的军政府和寻求独立的军政府之间的分歧反映了西班牙殖民地美洲更广泛的紧张关系。一方面,在启蒙思想和其他地方革命实例的推动下,人们对自由和自决的渴望与日俱增。另一方面,在实用主义考虑和对西班牙王室忠诚的指导下,人们渴望维护现有秩序。保守势力与进步势力之间的这种紧张关系在独立战争中以及在这些冲突中产生的新国家的形成过程中是一个反复出现的主题。是忠于摄政委员会还是追求独立,这不仅仅是一个政治忠诚度的问题,而是揭示了这些领土在未来愿景以及社会和政府组织方式上更深层次的分歧。

两党之间的分裂大大削弱了摄政委员会的权威,使其维持对殖民地控制的努力变得更加复杂。局势变得复杂而混乱,一些省份走向独立,而另一些省份仍忠于帝国。由于各省之间的忠诚度和目标不同,很难协调统一的帝国政策。此外,摄政委员会还必须面对许多军政府的不信任和敌视,这些军政府认为摄政委员会是西班牙统治的延伸,而不是合法政府。美洲殖民地权威和权力的这种分裂与西班牙国内的情况如出一辙,摄政委员会和国会也面临着分裂和挑战。美洲局势的复杂性给本已动荡不安的西班牙帝国雪上加霜。由于无法找到共同点并保持对殖民地的有效控制,独立运动获得了基础和动力。各省之间的深刻分歧和利益冲突造成了难以实现统一的环境,追求独立成为许多地区越来越有吸引力的选择。最终,各省之间的分裂和摄政委员会合法性的丧失导致了西班牙美洲殖民帝国的解体。在这些分裂和对殖民政府的普遍不满的推动下,独立运动最终成功地打破了与西班牙的关系,建立了新的主权国家。

美国某些省份宣布独立并不是一个统一或自发的行为,而是一个渐进和复杂的过程,反映了美国的政治、经济和社会状况。这一决定并没有得到普遍接受,民众的反应也大相径庭。克里奥尔精英往往是独立运动的领导者,他们有自己的利益和动机,但不一定得到全体人民的认同。一些人试图摆脱限制其经济和政治权力的西班牙监护。另一些人则受自由主义理想的驱使,寻求建立更加民主和更具代表性的治理。然而,也有一些重要的群体担心独立的后果。一些人担心独立会导致不稳定和混乱,另一些人则担心在即将出现的新秩序中失去自己的地位和特权。工人阶级的利益往往被忽视,独立并不一定会给所有人带来明显的好处。地区差异、社会分裂和经济差异使局势更加复杂。一些地区比较繁荣,与西班牙断绝关系会带来更多好处,而另一些地区则更加依赖大都市,担心独立会带来经济后果。随着时间的推移,这些紧张关系和矛盾塑造了独立之路,导致独立进程支离破碎,有时甚至混乱不堪。宣布独立往往是不同群体和利益之间漫长谈判、冲突和妥协的结果。美洲殖民地从西班牙独立并不是一个简单或线性的现象。它植根于一个复杂的局面,反映了美洲人民不同的现实和愿望。独立之路充满了不确定性和挑战,需要在不断变化的政治和社会环境中谨慎前行。

从 1809 年到 1814 年,西班牙美洲局势的特点是内部冲突而非真正的独立战争。在每个省份,希望忠于摄政委员会和西班牙国王的人与希望获得更大自治权甚至完全独立的人之间的矛盾都在沸腾。这些冲突往往深深植根于当地的社会、经济和政治分歧,反映了社会不同阶层之间在观念和利益上的差异。在一些省份,对帝国的忠诚度很高,尤其是在保守的精英阶层,他们将摄政委员会视为秩序和稳定的保障。他们担心自治或独立会引发社会动荡,威胁到他们的特权和地位。另一方面,在其他省份,自治和独立的呼声日益高涨。这些运动通常由克里奥尔精英和自由派知识分子领导,他们对在议会中代表权不足和限制性殖民政策的延续感到沮丧。他们认为自治和独立是促进改革和掌握自己命运的一种手段。在同一个省或地区内,人们的态度和效忠对象也可能大相径庭,这也使得情况变得更加复杂。在某些情况下,相邻的城镇或地区可能会严重分裂,忠于政府的派别和自治派别为争夺控制权而大打出手。这些内部冲突往往因西班牙局势的不确定性和混乱而加剧,当时西班牙正处于权力过渡时期,帝国前途未卜。消息传递缓慢,信息不完整或相互矛盾,加剧了不确定性和不信任。这一时期西班牙美洲历史的特点是相当复杂和模糊。这不是一场简单、连贯的独立斗争,而是一系列相互关联的冲突,反映了当地的分裂和不同的利益,以及西班牙帝国更广泛局势的影响。独立之路漫长而曲折,这一时期的冲突和紧张局势为以后的斗争奠定了基础。

美国独立战争远非简单或有序的冲突。这些冲突往往十分残酷,造成了重大的人员伤亡和财产损失,并使社区和家庭四分五裂。这些冲突的另一个特点是不断变化的联盟和背叛,增加了局势的复杂性和不确定性。在许多省份,不同的团体和派别都在争夺控制权,每一方都在寻求促进自己的利益和理想。克里奥尔精英、军官、土著团体和其他派别各怀鬼胎,他们之间的联盟可能是脆弱的、暂时的。效忠对象的迅速转变十分频繁,忠诚度可能会受到当时的机遇和压力的考验。当个人和团体试图在瞬息万变的政治环境中游刃有余时,背叛也屡见不鲜。为了在冲突中取得优势,人们可能许下诺言,也可能食言;可能达成协议,也可能放弃;可能结盟,也可能解散。这些战争的残酷性也令人震惊。战斗可能十分激烈,双方都经常犯下暴行。平民经常陷入战火之中,遭受暴力、饥饿和财产破坏。城镇和整个地区都可能遭到破坏,对当地经济和整个社会造成持久影响。这些内战最终导致西班牙在美洲的大部分殖民地获得独立,但独立之路是复杂、混乱和代价高昂的。这些冲突留下了深深的伤痕,它们造成的分裂和紧张局势在战争结束后的许多年里仍然影响着这些地区的政治和社会。

西班牙美洲的独立战争是地方和地区冲突的复杂拼图,而不是一场统一的运动。每个地区都有自己的动态、领导人和愿望,冲突发生的时间和激烈程度也各不相同。欧洲拿破仑战争的结束和国王斐迪南七世于 1814 年重返王位标志着一个转折点。斐迪南国王废除了 1812 年的自由宪法,在西班牙重建了专制制度。这种镇压鼓励了美洲的独立势力,他们认为自己的事业是保护自由主义成果和摆脱西班牙统治的一种手段。美洲几个独立国家的出现并没有结束冲突。相反,一些地区的独立战争一直持续到 1825 年,战事激烈,往往十分残酷。这些冲突的特点是联盟易变、背叛和极不稳定。独立之路并不平坦。有些地区很快就实现了独立,冲突相对较少。而在另一些地区,独立则是长期战争的结果,代价高昂,破坏严重,人员伤亡惨重。即使在独立之后,挑战也远未结束。新独立的国家面临着重大问题,如确定边界、建立稳定的政府、协调各种利益和派别、在多年战争和破坏后进行重建。总之,西班牙美洲的独立战争是一个复杂、多面的过程。它们反映了当地和地区的紧张关系、不同的愿望和不断变化的时代现实。从殖民统治到独立的过渡是一条艰辛的道路,充满了挑战和矛盾,在战争结束很久之后,人们仍能感受到这些冲突的影响。

西班牙美洲大陆:独立进程的多样性(1814-1824 年)

1814 年,拿破仑战败,国王斐迪南七世重返西班牙王位,拉丁美洲的局势达到了一个临界点。费迪南七世重新行使专制主义权力,否决了在他缺席期间制定的自由主义的《1812 年宪法》。这一决定不仅没有平息动荡的殖民地,反而加剧了他们在经济和政治上的不满。拉丁美洲的克里奥尔精英已经对缺乏代表权和不平等感到沮丧,他们认为否决《宪法》是对其争取更大自治权和权利的愿望的背叛。这一决定催化了整个拉美大陆的独立运动浪潮,将潜在的紧张局势转化为公开的冲突。这些独立斗争的特点是漫长、残酷和复杂。双方都进行了激烈的战斗,都犯下了暴行。联盟时而建立,时而破裂,英雄时而出现,时而倒下,平民百姓常常陷入战火之中。尽管面临诸多挑战和牺牲,大多数殖民地还是在 1824 年成功获得了独立。但这仅仅是他们历史新篇章的开始。事实证明,建国和创建稳定、包容的政府是一项艰巨的任务。新独立国家必须克服重重困难,包括确立民族身份、调和内部分歧、建立有效的机构以及治愈多年战争留下的创伤。

面对美洲殖民地日益壮大的独立运动,西班牙国王斐迪南七世采取了坚决的重新征服行动。他非但没有寻求通过谈判解决问题,也没有满足更多自治和权利的要求,而是选择了镇压的道路。斐迪南七世的战略是向殖民地派遣军队,其明确目的是重新确立西班牙的控制权。这场战役的特点是使用蛮力和无情镇压。西班牙军队毫不犹豫地使用一切必要手段镇压叛乱,包括逮捕、处决和流放众多独立领袖。领导反抗的克里奥尔精英和其他人物面临着严厉的镇压。许多人被监禁,一些人被处决,还有一些人被迫流亡。所传达的信息很明确:任何反对西班牙王室的行为都将遭到无情的打击。但是,镇压非但没有摧毁反抗精神,反而激发了独立运动。在对自由、自决和正义的强烈渴望的驱使下,独立战士们拒绝屈服。他们继续战斗,常常克服重重困难,做出巨大的个人和集体牺牲。争取独立的斗争跨越十年,经历了无数次战斗、挫折和胜利。道路漫长而艰难,但殖民地人民的决心从未动摇。最终,尽管西班牙拼命维护自己的统治,但大多数殖民地还是在 1824 年成功获得了独立。斐迪南七世的重新征服失败了,但它留下的伤痕却深刻而持久,并继续影响着新独立国家的记忆和身份认同。

Mexico

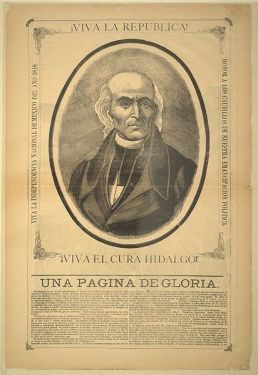

The independence movement in Mexico, sparked off by Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, is a fascinating and complex chapter in the country's history. Hidalgo, a white priest born in Mexico, had become increasingly indignant at the injustice and brutality with which the Mexican people were treated by the Spanish authorities and the Spanish-born elites, known as "gachupines." Inspired by a desire for change and a vision of a fairer, more inclusive government, Hidalgo took a bold step in 1810. He launched an open rebellion against the Spanish, calling on Mexicans of all origins, races and social classes to join him in the fight for independence. His call was a rallying cry, transcending the deep divisions that had marked Mexican society. Hidalgo's rebellion met with initial success. The troops, galvanized by their cause and charismatic leader, won several victories. But the Spanish army, well-equipped and determined, finally got the upper hand. Hidalgo was captured, tried and executed in 1811. His death was a blow to the movement, but far from ending the struggle, it actually strengthened it. Hidalgo's rebellion had lit a spark, and the flame of independence continues to burn. Under the leadership of other heroic figures, such as José María Morelos and Vicente Guerrero, the War of Independence continued for 11 tumultuous years. It was a period marked by fierce battles, courageous sacrifices and unshakeable determination. Finally, in 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain. Hidalgo's dream was realized, but the price was high. The memory of Father Hidalgo and his companions remains etched in Mexican history, a symbol of the struggle for justice and freedom. Their legacy continues to inspire future generations, reminding us that courage and conviction can triumph over even the most formidable obstacles.

Hidalgo's rebellion was primarily a political and social movement, although his character as a priest certainly influenced his role and the way he was perceived. His desire to end Spanish rule, eliminate inequality and create a fairer, more equitable government were at the heart of his rebellion. Hidalgo's call for revolution was not simply a call for national independence, but also a cry for social justice. He wanted to break the caste system that kept the vast majority of the Mexican population in poverty and subservience. That's why his movement attracted so many peasants, natives and mestizos, who were the most oppressed by the colonial system. Class dynamics took on considerable importance during the rebellion, and Hidalgo's troops targeted haciendas and other symbols of Creole wealth and power. This intensification of class struggle may have exceeded what Hidalgo had initially anticipated, and it certainly complicated his efforts to maintain control and unity within his movement. Despite these challenges and the divisions within his forces, Hidalgo's rebellion had a profound impact. It helped shape Mexican national identity and define the goals and values of the struggle for independence. After Hidalgo's death, the cause of independence was taken up by other leaders, including José María Morelos and Vicente Guerrero, who continued to fight against oppression and injustice. Their legacy, like Hidalgo's, still resonates today in Mexico's history and culture, reminding us of the importance of justice, equality and freedom.

After Hidalgo's capture and execution, José María Morelos, who was also a priest, took up the struggle and was a gifted military and political leader. Morelos' vision went beyond purely political independence and embraced far-reaching social reforms. He was particularly concerned about racial and economic inequality, and called for the abolition of slavery, land redistribution and equality for all citizens, regardless of race or social origin. His progressive ideals were incorporated into the document known as the Sentiments of the Nation, which was adopted by the Congress of Chilpancingo in 1813. This document was a proclamation of the principles and objectives of the independence movement, and served as the basis for the future Mexican constitution. Morelos succeeded in controlling a significant part of the country, but had difficulty maintaining control of his troops. Internal divisions and ideological differences weakened the movement, and Morelos himself was captured and executed by the Spanish in 1815. Despite these setbacks, the War of Independence continued, largely thanks to the commitment and determination of leaders like Vicente Guerrero. Eventually, the Spanish colonial forces were worn down, and the Plan d'Iguala in 1821 led to a negotiated independence, sealing Mexico's independence. The ideals and legacy of these great leaders, like Hidalgo and Morelos, continued to influence Mexican politics and national identity long after their deaths, and they are commemorated today as national heroes in Mexico.

The end of the Mexican War of Independence and the role of Agustín de Iturbide are crucial chapters in the history of Mexican independence. Agustín de Iturbide was originally a royalist officer in the Spanish army. However, he understood that the tide was turning in favor of independence and sought to position Mexico (and himself) advantageously in this new reality. He negotiated with Vicente Guerrero, one of the insurgent leaders, and together they drew up the Plan d'Iguala in 1821. The Plan d'Iguala proposed three main guarantees: the Catholic religion would remain the nation's sole religion, Spaniards and Mexicans would be equal before the law, and Mexico would be a constitutional monarchy. These proposals helped win the support of various groups, including conservatives concerned with maintaining social order. Following acceptance of the plan by the various parties, Iturbide led the Army of the Three Guarantees, named after the three key principles of the Plan d'Iguala, and quickly secured Mexico's independence. Iturbide then proclaimed himself emperor in 1822, but his reign was short-lived. His government was unpopular with many sectors of society, and he was overthrown in 1823. Mexico then became a republic, and the process of nation-building and political stabilization began, a process that was marked by continuous conflict and struggle throughout the 19th century. Mexico's path to independence illustrates the complexity and challenges inherent in the creation of a new nation, particularly in a context of deep social and economic divisions. The ideals of independence have continued to influence Mexican politics and society for decades, and the heroes of the struggle for independence are commemorated each year in the celebration of Independence Day on September 16.

Independence in Central America was more peaceful than in other parts of Latin America. On September 15, 1821, the leaders of the General Captaincy of Guatemala, which encompassed what are now Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, signed the Central American Act of Independence. This document proclaimed their independence from Spain, but there was no clear consensus on the way forward. Shortly after independence from Spain, Central America was briefly annexed to Iturbide's Mexican Empire in 1822. After the collapse of the Iturbide Empire in 1823, Central America separated from Mexico and formed the Federal Republic of Central America. The Federal Republic was marked by internal conflicts and tensions between liberals and conservatives, as well as regional differences. It finally broke up in 1840, with each state becoming a sovereign nation. Central American independence is therefore unique in that it was not the result of a long and bloody war of independence, but rather of a combination of internal and external political and social factors. The process reflects the diversity and complexity of independence movements in Latin America, which were influenced by local, regional and international factors.

Venezuela

In Venezuela, the independence movement emerged as an effort led by wealthy Creole elites, motivated by a desire for greater autonomy and political power away from the Spanish colonial yoke. However, this quest did not take place in a vacuum; it came up against the complexity of a diverse society, characterized by the presence of large numbers of enslaved Africans and indigenous peoples. The situation was further complicated by the influence of revolutionary movements abroad, in particular the example of Haiti. The Caribbean island had succeeded in gaining independence from France thanks to a slave rebellion, and the other sugar-producing West Indies were also experiencing slave revolts. These events awakened in the Creole elites both a sense of inspiration and fear, prompting them to seek independence for their own benefit while being aware of the underlying tensions with the lower classes. These lower classes, composed mainly of slaves and natives, also aspired to freedom and equality, but their interests did not necessarily coincide with those of the Creole elites. The resulting tension between these divergent groups created a volatile terrain and shaped the independence movement in a unique way. Instead of a straightforward transition to autonomy, Venezuela found itself in an internal struggle to define what independence would mean for its entire population. The result was a path to independence marked by conflict and compromise, in which questions of race and social inequality played a central role. This tension did not disappear with the achievement of independence in 1821; it continued to shape the country's political and social development, leaving a complex legacy that continues to influence contemporary Venezuela.

Venezuela, a colony with a large population of enslaved Africans, faced a complex dynamic during its independence movement. In this context, slavery was more developed than in Mexico, with many cocoa plantations using slave labor. Society was also made up of a large number of freedmen of color, working mainly in urban crafts, but not held in the same esteem as the white Creole elites. The complexity of this social structure created an atmosphere of mistrust and hesitation among the Creole elite. The substantial presence of slaves and the prospect of a revolution similar to that in Haiti, where slaves had risen up against their masters, sowed doubts about the way forward. Rather than seeking total independence, which could lead to a loss of control over the slave population and provoke social upheaval, the elite was more inclined to seek greater autonomy within the Spanish empire. This cautious approach reflected the underlying tensions and concerns running through Venezuelan society at the time. The fear of a slave rebellion not only influenced the trajectory of the independence movement, but also continued to shape Venezuela's political and social development long after its independence in 1821. The struggle to balance desires for independence with the realities of social and racial inequality left a complex legacy, marking the beginning of a nation that had yet to define itself in a post-colonial world.

Venezuela's independence process was distinct from that of Mexico, and was characterized by internal divisions and racial and social tensions. The movement began in 1810, when the junta declared independence. However, this declaration failed to resonate with the working classes, who were mistreated by the elites, and continued to be subjected to slavery and exploitation. The Spaniards, who still had troops in the region, skilfully played on these tensions. By denouncing the racism of the Creole elites and promising freedom to the enslaved populations, including the llaneros (cowboys) of the haciendas, they succeeded in mobilizing the non-white plantation troops. This movement caused a split in the independence forces, with the Creole elites and their troops on one side, and the forces raised by Spain on the other. As a result of this division, the independentists were quickly outnumbered by the Spanish troops. The war for independence dragged on for another decade, marked by the rise of figures such as Simon Bolivar and Francisco de Paula Santander. Venezuela finally gained its independence in 1821, along with the other territories of Greater Colombia. But the path to a unified nation and stable governments was far from simple or straightforward. The internal conflicts and power struggles that had marked the independence movement continued to weigh heavily on the country, and the nation-building process proved to be a long-term challenge. The complexity of the social situation and the divisions between different factions have shaped Venezuela's history, leaving a legacy that continues to influence the country's politics and society to this day.

In Venezuela, the struggle for independence was a complex and turbulent process, marked by civil war and internal divisions. Simon Bolivar, a member of the cocoa aristocracy and a slave trader, emerged as a central figure in this struggle. Aware of the socio-economic reality of his country, where the majority of the population was poor, indigenous and of African descent, Bolivar recognized the need to broaden support for the independence movement beyond the Creole elites. He understood that a Spanish victory would not lead to equality for people of African descent, nor to the abolition of slavery, as the Spanish Constitution of 1812 made clear. So Bolivar took the bold step of forming alliances with people of diverse ethnic and social origins. He promised them equality and freedom, commitments that were not merely rhetorical. He took concrete steps, such as abolishing slavery in Venezuela, which won him the support of the enslaved population. These strategic decisions, combined with his charismatic leadership and military skills, enabled Bolivar and his army to defeat the Spanish army. He did not stop there, however, and continued the fight for independence in other territories of Gran Colombia. Bolivar's legacy remains a powerful symbol in Latin America. He is revered as a liberator who transcended divisions of class and race to unite a people in the quest for independence. His example and ideals continue to influence political and social thought in the region, reminding us of the complexity of independence struggles and the importance of inclusion and equality in building unified nations.

In 1813, Simon Bolivar, with a clear vision and a colossal challenge before him, launched a campaign against the Spanish, declaring a "war to the death of the Americans" that would transcend racial distinctions. This declaration was no mere rhetoric; it embodied a fundamental strategic shift in the struggle for Venezuelan independence. Bolivar realized that victory over the Spanish would require unprecedented unity among the people of Venezuela. To achieve this, he adopted an inclusive approach, training military leaders from all backgrounds, without discrimination. He promoted black and mulatto officers and made a bold promise of freedom to slaves who joined the cause of independence. This innovative policy was a game-changer. It enabled Bolivar to win the hearts and minds of the enslaved population, who rallied to his army in large numbers. This diverse army, united in its desire for freedom, became a formidable force on the battlefield. The decisive victories that followed were not just the result of bravery or military tactics; they were the fruit of Bolivar's strategy, which recognized the importance of equality and inclusion in the struggle for independence. He led his troops through many battles, strengthening the legitimacy of his cause at every step. In 1821, Venezuela finally gained its independence, along with other territories in Greater Colombia, a success largely attributable to Bolivar's revolutionary approach. This victory was not just that of one man or one elite; it was the victory of a unified people who had been mobilized around a common ideal. The legacy of this struggle continues to resonate, offering a powerful example of how equality and inclusion can become not just moral principles, but strategic tools in nation-building.

When King Ferdinand VII returned to the Spanish throne in 1814 after the collapse of the Napoleonic regime, he swept aside liberal reforms, rejecting the Constitution of 1812, and sought to re-establish absolutist power over his American colonies. This retrograde decision had far-reaching consequences, not least the revival of Spanish efforts to reconquer their colonies in Latin America. Simon Bolivar, the liberator of Venezuela, found himself in a delicate position. Forced to flee in the face of renewed Spanish power, he took most of his troops and officers and fled to Haiti, a nation that had itself been shaped by a successful revolution against oppression. There, Bolivar found an unlikely but vital ally in the Haitian president Alexandre Pétion. Aware of the importance of Bolivar's struggle for the entire region, Pétion offered him refuge, support and even resources to relaunch the war for independence. This gesture of solidarity transcended borders, uniting the Venezuelan cause with that of Colombia and Ecuador. This alliance, fortified by a shared determination to put an end to colonial domination, enabled Bolivar to regain the initiative. Gradually, he succeeded in ousting the Spaniards and establishing a confederation of three nations, called Gran Colombia. It was an unprecedented triumph of diplomacy, strategy and regional unity, which lasted until 1831. Bolivar's story, from his exile in Haiti to the formation of Gran Colombia, is a powerful testament to how ambition, vision and international cooperation can transform the fortunes of a nation and a region. It continues to be a symbol of the struggle for freedom and self-determination, not only in Venezuela, but throughout Latin America.

The independence of Gran Colombia, a confederation comprising today's Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador and Panama, proclaimed in 1821, represents a complex and fascinating chapter in South American history. The road to independence was long and winding, littered with obstacles such as internal divisions and civil wars. The territories that made up Greater Colombia were profoundly different from one another. Each region had its own characteristics, with variations in ethnic, linguistic and cultural origins. In addition, economic and social disparities further complicated the unification effort. However, under the visionary leadership of Simon Bolivar and his collaborators such as Francisco de Paula Santander, these regions were able to overcome their differences and unite in their struggle for independence from Spain. Bolivar's dream was to form a strong, unified republic that would transcend regional divisions and offer a coherent national identity. The formation of Gran Colombia was a milestone in the nation-building process, an unprecedented achievement in a region torn by conflict. But it was also a fragile alliance, often beset by internal tensions and opposition from various factions. Despite its precarious nature, Greater Colombia survived for a decade, leaving a lasting legacy in the region. Its existence laid the foundations for regional collaboration and dialogue, inspiring independence movements throughout Latin America. The dissolution of Gran Colombia in 1831, however, was a stark reminder of the difficulty of maintaining unity in such a diverse region. This historic moment continues to resonate today, reflecting the challenges of national unity and governance in a context of cultural and social pluralism. It remains a symbol of both the aspiration for unity and the complex realities of regional politics.

Rio de la Plata (Buenos Aires)

In the early 19th century, Buenos Aires, newly promoted capital of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, embodied a vibrant and diverse microcosm of South America. This small port city was much more than just a commercial and administrative center; it was the melting pot of a composite society, bringing together Afro-descendants, members of military garrisons, gauchos (cowboys), and other ethnic groups. The year 1807 marked a turning point in the city's history. At that time, the British, seeking to extend their influence in the region, occupied Buenos Aires. But far from giving in, the city's inhabitants, in a burst of patriotism and determination, succeeded in driving out the invaders. This episode, though brief, had a profound impact on the collective consciousness of the population. The victory over the British not only strengthened the autonomy of Buenos Aires, but also awakened a sense of national identity and pride. This experience of resistance was a source of inspiration and a precursor to the subsequent struggle for independence. Resistance against British occupation was not simply a military conflict; it symbolized an assertion of autonomy and sovereignty that transcended the city's social and cultural divisions. The different groups that made up the population of Buenos Aires found in this struggle a common goal, forging a solidarity that would endure in the years to come. In this way, the 1807 episode in Buenos Aires was not simply an isolated historical event, but a crucial stage in the formation of an Argentine national identity. It laid the foundations for a political consciousness and an aspiration for independence that would culminate in Argentina's declaration of independence in 1816. The resistance of Buenos Aires remains a symbol of the indomitable spirit of a fledgling nation, and a reminder of the power of unity and determination in the quest for freedom and sovereignty.

In 1810, the spirit of independence that had been simmering in Buenos Aires reached boiling point, leading the city to declare its independence from Spain. But this quest for freedom was not a path without obstacles; it was complicated by internal divisions and the persistent presence of royalist forces in other parts of the viceroyalty. These divisions were rooted in differences of social class, economic interest and political vision. On the one hand, there were the supporters of independence who wanted to sever all ties with the Spanish crown, and on the other, the royalists who sought to maintain the status quo and loyalty to Spain. These differences created tensions and conflicts that made the road to independence arduous and complex. Despite these challenges, determination and unity between Buenos Aires and the surrounding provinces prevailed. After several years of struggle and negotiation, they finally achieved independence in 1816. This victory led to the formation of the United Provinces of Central America, a forerunner of what would later become the Republic of Argentina. The independence of Buenos Aires and its surrounding provinces was not just a triumph over colonial forces. It was also a victory over the internal divisions and dissensions that could have hampered the process. The transformation of the United Provinces of Central America into the Republic of Argentina illustrates the ability of these regions to overcome their differences, join forces and forge a nation. The road to Argentine independence remains an inspiring example of how perseverance, collaboration and a common goal can triumph over even the most daunting obstacles. He embodies the will of a people to emancipate themselves, forge their destiny and build a nation on the foundations of freedom, equality and unity.

José de San Martín is undoubtedly one of the most important figures in South American independence. His role was not limited to Argentina's independence, but extended far beyond its borders. He understood that the freedom of one nation could not be fully secured while neighboring regions remained under colonial yoke. This led to a series of military campaigns that played a decisive role in the liberation of South America. After gaining independence in 1816, Argentina faced a potential threat from Brazil and the viceroyalty of Peru. San Martín realized that Argentine independence would only be secure if neighboring regions were also liberated. San Martín undertook an arduous campaign to liberate Chile, planning and executing an epic crossing of the Andes in 1817. Joining forces with other independence leaders such as Bernardo O'Higgins, he succeeded in defeating the royalist forces in Chile and proclaiming that country's independence in 1818. Not satisfied with these successes, San Martín continued his mission to Peru, the nerve center of Spanish power in South America. After a series of battles and diplomatic negotiations, he succeeded in declaring Peru's independence in 1821. San Martín's vision and dedication were crucial in achieving these victories. His understanding of the interconnected nature of independence shaped the way freedom was won in South America. San Martín's campaigns not only liberated territories but also laid the foundations for regional solidarity and identity. His legacy continues to be celebrated in these countries, and his contribution to the cause of independence remains a shining example of leadership, strategic vision and determination.

Peru

Peru's independence came about in a unique context, shaped by a complex intersection of military and social forces. Caught between troops from the south, led by José de San Martín, and those from the north under the command of Simón Bolívar, the country was plagued by internal tensions exacerbated by elites loyal to the Spanish king. These elites deeply feared the repercussions of independence, particularly the threat of revolts similar to that led by Túpac Amaru II in the 18th century. This climate of fear was partly fuelled by the acute awareness that independence could mean the loss of power and privilege for these elites, who had much to lose in a post-colonial society. Their resistance to independence added a further layer of complexity to an already delicate situation, where the patriotic forces of San Martín and Bolívar had to navigate through politically fragmented terrain. However, despite these obstacles, the synergy between the combined forces of San Martín and Bolívar proved decisive. Their successive military victories against the Spanish army slowly but surely eroded elite resistance and paved the way for independence. In 1821, Peru finally overcame these challenges and officially declared its independence, ushering in a new era as a republic. The trajectory of Peruvian independence thus illustrates not only the complex dynamics of the war of liberation, but also the underlying tensions and contradictions that can characterize a society in transition. It is a rich and nuanced chapter in Latin American history that continues to resonate in Peru's national consciousness.

Peru's road to independence, although officially declared in 1821, did not end there. Spanish colonial resistance persisted in the region, representing an ongoing threat to the independence forces. This confrontation finally crystallized in the Battle of Ayacucho, a major conflict that took place in 1824. The Battle of Ayacucho was much more than a simple military confrontation; it was a symbol of the struggle for self-determination and freedom. The combined forces of Simón Bolívar and his loyal lieutenant, Antonio José de Sucre, were put to the test against the Spanish army led by General José de Canterac. The victory of the independence forces at Ayacucho not only marked the end of the Spanish presence in Peru, it also sounded the death knell for the Spanish Empire in South America. The triumph at Ayacucho was considered the final and decisive battle of the Spanish American Wars of Independence. This key moment in history was a turning point not only for Peru, but for the entire South American continent. After the battle, the Spanish Empire lost control of all its territories in South America, allowing these regions to forge their own destinies as independent countries. The Battle of Ayacucho therefore remains an emblem of freedom and resistance, a testament to the determination and unity of the peoples of South America in their quest for sovereignty. It is a commemoration of the courage, strategy and sacrifice that transformed a region under colonial rule into a mosaic of free and sovereign nations.

The consequences of independence processes

The Wars of Independence in mainland Spanish America, from 1814 to 1824, ushered in a period of radical transformation that had major repercussions for both Spain and the emerging nations of Latin America. For Spain, the loss of control over the American continent was a devastating blow to its prestige and economic power. While most of its colonies on the continent became independent, it managed to retain its possessions in the Caribbean, notably Cuba and Puerto Rico. Cuba, nicknamed the "Pearl of the Antilles", took on particular importance after Haiti's independence, becoming the main supplier of sugar and a jewel in the Spanish colonial crown. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, continued to play a significant strategic and economic role for Spain. However, even these bastions of the Spanish empire were destined to fade away. Spain finally lost control of Cuba and Puerto Rico in 1898 as a result of the Spanish-American War, marking the definitive end of the Spanish empire in the Americas. For the newly independent nations of Latin America, the post-colonial era was both promising and challenging. Independence brought an unprecedented opportunity to forge a national identity and determine their own political and economic path. However, they have also had to contend with internal problems, such as social divisions, civil wars, and the building of stable political institutions. The legacy of Latin America's wars of independence is therefore complex. It represents both the end of an old colonial order and the beginning of a new era of self-determination and nation-building. This process, though full of uncertainties and conflicts, laid the foundations for the region as we know it today, with its cultural richness, diversity and democratic aspirations.

On the other hand, the newly independent countries of Latin America faced monumental challenges in their quest for nation-building and the creation of stable governments. The process was far from straightforward, as the obstacles were many and deep-rooted. The territories that made up these new nations had very diverse ethnic, linguistic and cultural origins, reflecting a complex mosaic of peoples and traditions. This diversity, while an asset, complicated the task of forging a cohesive national identity and a shared sense of belonging. In addition, social and economic structures were deeply marked by the legacy of colonialism and slavery. Social inequalities were deeply rooted, and the economy was often dependent on a few export products, leaving nations vulnerable to the fluctuations of world markets. Local elites, who had often played an important role in independence movements, now had to navigate these challenges without the framework of colonial governance. Tensions between different social groups, regional aspirations and divergent political ideologies often led to conflict and political instability. Despite these challenges, the newly-independent countries resolutely set about building a new identity and sense of nationhood. It was a long and arduous process, with advances and setbacks, but one that ultimately led to the creation of distinct nation-states, each with its own characteristics and its own path to modernity. The experience of nation-building in Latin America remains a fascinating chapter in world history, illustrating both the possibilities and difficulties of creating new nations in the wake of colonial domination. It continues to inform and shape the region today, reflecting a complex and rich history that continues to resonate in the political, social and cultural life of Latin American nations.

General considerations

The process of achieving independence in Spanish America, which spanned the 20-year period from 1808 to 1828, is clearly distinct from that of the thirteen British colonies in North America and Haiti. Several factors contributed to this distinction, creating a complex path to independence. Firstly, the wars of independence in Spanish America lasted much longer. While the British colonies achieved independence in just eight years, from 1775 to 1783, and Haiti succeeded in gaining its own in a dozen years, from 1791 to 1804, the struggle in Spanish America lasted two decades. This prolonged period was marked by internal conflicts and civil wars, reflecting the immense complexity of the situation. Secondly, Spanish America was made up of a mosaic of territories with different ethnic, linguistic and cultural origins. This diversity led to regional divisions and tensions, making the task of creating a unified national identity and stable governments even more arduous. Different regions and social groups had often divergent interests and visions, fuelling internal struggles for power and influence. Thirdly, the presence of a large enslaved population added another layer of complexity. Issues relating to slavery and the rights of Afro-descendants provoked passionate debate and sometimes contributed to violent conflict. The question of slavery was a major issue in many regions, and its resolution was a key factor in the formation of new nations. Finally, the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires were geographically more extensive and culturally more heterogeneous than the British colonies in North America. This made the process of achieving independence more fragmented and varied, with different paths taken by different territories. Although sharing the common goal of independence, the process in Spanish America was profoundly complex and distinct from that in other parts of the Americas. It was marked by protracted struggle, internal divisions, cultural and ethnic diversity, and the complexity of dealing with issues such as slavery. This rich and multifaceted history has shaped the Latin American nations of today, leaving them with a complex and nuanced legacy that continues to resonate in their contemporary political and social development.

In addition to the military struggles that marked the path to independence, the process of nation-building in Latin America was a complex and ongoing undertaking. It was not simply a matter of breaking with the colonial yoke, but also of forging a new identity, establishing stable institutions and attempting to unite populations of diverse origins under a common national banner. Creating a sense of national identity was particularly challenging. In a region marked by great ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity, finding common ground that transcended local differences was no easy task. Tensions between different ethnic and social groups, economic disparities and regional divisions often hampered the formation of a cohesive national identity. Establishing stable governments was another major challenge. The new states had to create institutions that reflected both the democratic ideals of the time and local realities. Drafting constitutions, forming governments, establishing judicial systems and setting up public administration were complex tasks requiring delicate compromises and careful navigation between different factions and interests. In addition to these challenges, the newly independent countries also had to tackle economic problems inherited from the colonial system, such as dependence on certain exports, unequal land tenure structures and the marginalization of large sections of the population. Despite these obstacles, the process of nation-building eventually led to the formation of new nation-states in Latin America. It was a long, sometimes chaotic and difficult process, but it laid the foundations for modern Latin America. The lessons learned, the successes achieved and the failures suffered continue to inform the region's political and social trajectory, testifying to the complexity and richness of its history of independence and nation-building.

The process of achieving independence in Spanish America was a long and complex one, marked by dynamics that were far from uniform. Several factors, including the multiplicity of factions, socio-racial divisions, geography and the absence of external support, contributed to this complexity. At the heart of the struggle for independence was the presence of several factions with different goals and motivations. Royalists sought to maintain the status quo, while autonomists and independentists had divergent aspirations. This diversity of opinion created fertile ground for internal conflict, making it difficult to establish a clear path to independence. The fractured nature of these groups added a layer of complexity to an already complicated situation. These internal conflicts were exacerbated by the deep socio-racial divisions of colonial society. The complexity of the social hierarchy and tensions between different classes and ethnic groups prolonged the struggle. Each group had its own expectations and fears regarding independence, which often translated into tension and conflict. The transition between these social tensions and regional dynamics was the geography and colonial administration of Spanish America. The vast geographical expanse and administrative fragmentation into several viceroyalties created distinct regional dynamics. Each region, with its cultural, economic and political particularities, presented a unique challenge in coordinating a unified independence movement. Finally, unlike other independence movements, Spanish America did not benefit from significant external support. This slowed down the process, as pro-independence forces had to fight without the help of major foreign powers. This lack of international support accentuated the isolation of the pro-independence forces and prolonged the duration of the conflicts. The internal, fragmented nature of the struggle for independence in Spanish America, coupled with the complexities of socio-racial and geographical factors, and the absence of external support, made the process both long and complex. It was a time of turbulence and transitions, when a single group's victory was difficult to achieve, and when it took time, diplomacy, strategy and often compromise to reach a consensus on independence.

The absence of substantial and consistent external aid was a determining factor in the prolongation of the wars of independence in Spanish America. With the notable exception of Venezuela, which received some support from Haiti, the Spanish colonies fighting for independence received little or no international support. Unlike the thirteen American colonies, which received substantial aid from France, Spanish America was largely left to its own devices. This situation contrasted sharply with other independence movements of the time. The lack of external assistance also extended to military and financial aspects. Colonies seeking independence had to make do with limited military resources, without the support of foreign armies. Conflict financing was also precarious, and the colonies had to rely heavily on credit from England. This reliance on foreign credit to finance wars left the newly independent nations with a substantial foreign debt. This not only complicated the independence process but also created long-term economic challenges for these nations, hampering their development and stability long after independence. The lack of international aid, whether military, financial or diplomatic, contributed to the lengthening of the independence process in Spanish America. Dependence on foreign credit and lack of military and political support not only prolonged conflicts, but also left a legacy of debt and economic hardship for emerging nations. The trajectory of independence in Spanish America thus illustrates how international and economic factors can play a crucial role in shaping an independence movement.

Spain's stubborn resistance to recognizing the independence of its Latin American colonies also played a crucial role in prolonging the wars of independence. Spain's determination to hold on to its territories in Latin America was another key factor in the protracted struggle for independence. Unlike some colonial powers that were able to negotiate more peaceful transitions to independence, Spain chose to fight vigorously to retain its colonies. The economic and strategic value of these territories to Spain fueled a fierce resistance that made the struggle for independence both longer and bloodier. Even after most of the colonies had achieved de facto independence, Spain was slow to officially recognize this new reality. For example, it was not until 1836 that Spain officially recognized Mexico's independence, even though the country had achieved de facto independence in 1821. This slow pace of official recognition contributed to instability and uncertainty in the post-independence period. Spain's resistance to the independence of its colonies, combined with the slow pace of official recognition, added another layer of complexity to the struggle for independence in Spanish America. Spain's determination to maintain control and its subsequent refusal to quickly recognize the new political reality prolonged conflicts and left a legacy of instability. Together, these factors illustrate why the independence process in Latin America was so complex and protracted, shaped by a multitude of internal and external challenges.

The cost of the wars of independence in Spanish America was considerable, and manifested itself in different ways across the region. The cost of the wars of independence in Spanish America was unevenly distributed across the different territories, reflecting the region's diverse geographical, social and economic contexts. In Venezuela and the Caribbean coast, as well as in Colombia, the human cost of the war was particularly high. Destruction, fighting and famine have led to a considerable decline in the population. These regions, with their dense populations and slave-based economies, were deeply marked by conflict. Slaves played an essential role in these economies, and many joined the struggle for independence, seeking their own freedom. As a result, they were caught in the crossfire of war, increasing casualties and contributing to social instability. The economic impact of the wars of independence was also marked. The destruction of infrastructure, the disruption of trade and the collapse of slave-based economies left these regions in a state of economic devastation. In addition, the foreign debt incurred to finance the war weighed heavily on the economies of the newly independent countries. The Wars of Independence in Spanish America left a complex and painful legacy. The loss of life, particularly in regions such as Venezuela, Colombia and the Caribbean coast, was devastating. The social and economic consequences of the war extended well beyond the end of the conflicts, posing challenges of reconstruction and reconciliation that have shaped the development of Latin American nations. The participation and sacrifice of slaves in the struggle for independence added another dimension to these challenges, reflecting the complexity of the region's social and racial dynamics.

In terms of economic losses, Mexico represented a particularly striking case in the Latin American wars of independence. The Mexican War of Independence, which lasted over a decade, had a devastating impact on the national economy. Mexico's mining infrastructure, the backbone of its economy, suffered massive destruction during the war. Mines, which were essential to the country's exports and wealth, were subject to conflict and sabotage, seriously disrupting mining activity. This situation had a considerable impact on the Mexican economy, not only reducing revenues from the export of precious metals, but also affecting other sectors linked to the mining industry. The destruction of the mining infrastructure also created an economic and social vacuum in regions where mining was the main source of employment and income. Post-independence reconstruction was slow and difficult, and the loss of this key industry hampered Mexico's ability to recover quickly. In addition, the war left the country with a large debt and a devalued currency, further exacerbating the economic problems. Mexico's dependence on its mines and the loss of this vital resource was a major blow to the young nation, highlighting the economy's vulnerability to conflict and political change. The economic losses suffered by Mexico during the War of Independence were a major factor in the challenges the country faced in the years following independence. The destruction of the mining infrastructure, in particular, was a major obstacle to reconstruction and development, and left an economic legacy that influenced Mexico's path to modernization and stability.

Argentina presents an interesting contrast with Mexico in terms of the cost of independence and post-conflict recovery. Argentina's independence was achieved at a lower cost, leading to a faster economic recovery. Unlike Mexico, Argentina's economy was more focused on agriculture. The country's vast, fertile pampas were relatively untouched by the destruction of war, allowing farming and ranching to continue to thrive. This was crucial to the economic recovery, as these sectors quickly responded to the needs of the population and the demands of exports. In addition, Argentina had a relatively small slave population, which reduced the complexity and costs associated with the war. Social conflicts and racial tensions were less pronounced, contributing to a more peaceful transition to independence. Argentina's geographical position, further from the heart of the Spanish empire, and the presence of competent military leaders such as José de San Martín, also worked in its favor. The combination of these factors enabled Argentina to minimize human and economic losses and lay the foundations for more stable post-independence development. Argentina's transition to independence illustrates how geographical, economic and social factors can influence a country's trajectory in a period of radical change. Limited dependence on the mining industry, the strength of agriculture and the absence of major social tensions helped Argentina successfully navigate the tumultuous waters of independence and emerge with a solid foundation for future growth.

The Wars of Independence in Spanish America, spanning from 1808 to 1828, are a fascinating and complex chapter in world history. These conflicts, involving a diverse and massive mobilization of the population, can be seen as a "real revolution". However, the nature of this revolution deserves a more nuanced analysis. On the one hand, the dynamics of revolution were evident in the participation of different social groups, including slaves, who united in the struggle for independence. Moreover, the ideological struggle between royalists, autonomists and independentists, each fighting for different goals, added complexity and depth to the revolution. Finally, the concrete struggle for power, where different factions fought for control of territories, underlined the revolutionary nature of these wars. However, it is essential to note that the revolution did not bring about a profound transformation of social and economic structures in most of these countries. Structures inherited from the Spanish colonial system, such as slavery and racial hierarchy, persisted long after independence. The elite that held power before and after the wars remained largely unchanged, and social and economic inequalities continued to prevail. In short, while the wars of independence in Spanish America can be considered a revolution in terms of popular mobilization, ideological conflict and the struggle for power, their impact on social and economic structures was more limited. Continuing inequalities and the legacy of colonialism show that the revolution was incomplete, leaving a complex and sometimes contradictory legacy for the newly-formed nations. This crucial period of history continues to shape politics, economics and society in Latin America, and understanding it offers essential insights into the challenges and opportunities that still face us today.

The wars of independence in Spanish America presented a complex mix of ideology, promise and reality. Led primarily by white elites, these wars saw the crucial participation of troops of color, including mestizos, black mulattos and natives. The dominant ideology of the time, centered on the principles of liberty, equality and private property, played a central role in motivating these troops. The elites promised these ideals to the lower classes, arousing their support for the cause of independence. These promises not only represented a call for justice and fairness, but were also a strategic tactic for mobilizing a significant force in the struggle against colonial domination. However, the transition from promise to reality proved to be a rocky road. Despite proclamations of equality and freedom, newly independent countries often inherited the social and economic structures of the colonial period. Marginalized groups who had fought with hope and conviction found their rights and opportunities severely limited in the new society. Inequality and discrimination persisted, and promised ideals were often at odds with everyday reality. Despite these disappointments and contradictions, the participation of troops of color in the wars of independence remains a vital and often overlooked aspect of this historic period. Their courage, determination and sacrifice were a key factor in the ultimate success of the independence movement, and their story contributes to a richer, more nuanced account of the birth of nations in Latin America. This contrast between ideals and reality continues to be a subject of reflection and debate in contemporary analysis of Latin American history. It underlines the complexity of liberation movements and the need to examine carefully the power dynamics, unfulfilled promises and lasting legacies of these historic struggles. The story of the colored troops in the wars of independence offers valuable insight into the persistent challenges of inequality and injustice in the region, and remains a powerful reminder of the capacity for resilience and hope in the pursuit of freedom and dignity.

Independence in Spanish America marked a formal break with the colonial past, symbolized by the adoption of republican regimes in almost all countries, with the notable exception of Mexico under the Iturbide regime. This period of change was characterized by the abolition of the nobility and the removal of all references to race from constitutions, laws and censuses. These measures were representative of the desire to create modern, egalitarian nation-states, breaking with the hierarchical and discriminatory system of colonialism. However, these legal and constitutional changes did not necessarily lead to a concrete transformation of socio-economic structures. Despite legal reforms, the deep-rooted inequalities and social divisions of the colonial period persisted. Marginalized groups, who had often fought alongside pro-independence forces, found that their rights and opportunities remained severely limited. Elites, who had led the independence movement, often maintained control over economic resources and political power, even after colonialism ended. The promise of a more equitable and inclusive society remained largely unfulfilled, and the social and economic structures of the colonial system continued to influence life in the newly independent countries. This discrepancy between republican ideals and socio-economic reality posed a major challenge for the young republics of Latin America. It sowed the seeds of tensions and conflicts that persisted for many decades after independence. The struggle to realize the ideals of freedom, equality and justice remains an integral part of Latin America's history and identity, and a reminder of the complexity and nuance needed to understand the region's nation-building process.

The abolition of slavery in Latin America was a historic turning point and an essential element of post-independence reforms. It marked the end of an inhumane and barbaric institution that had sustained colonial economies for centuries. However, abolition was no panacea for the deep-rooted evils of racism and discrimination that persisted in society. Despite the formal abolition of slavery, former slaves and their descendants continued to face systemic obstacles to equality. Socio-economic structures did not change overnight, and the former slave population was often left without access to education, land, jobs or economic opportunities. Citizen status, although theoretically granted, was in practice hampered by persistent discrimination. Skin color continued to influence the way individuals were perceived and treated in society. Racism and racial discrimination, rooted in the colonial period, persisted and shaped social, economic and political relations. The abolition of slavery did not eradicate these attitudes, and people of African descent were often marginalized and excluded from spheres of power and influence. The experience of Latin American countries in the post-independence period highlights the challenges inherent in transforming society and achieving true equality. The abolition of slavery was a necessary but insufficient step towards remedying deep-rooted inequalities. The legacies of colonialism and slavery have continued to shape life in these countries, and the struggle for equality and justice is an ongoing process, still relevant in the contemporary context.

While the struggle for independence led to the end of the colonial yoke and the formation of new nation-states with republican regimes, these political and legal changes were not accompanied by a profound transformation of socio-economic structures. The newly independent countries inherited a system deeply rooted in the social, economic and racial inequalities of the colonial period. The abolition of slavery, while an important step towards equality, did not erase the legacies of colonialism or bring about real, substantive equality. The old elites often retained power, and economic inequalities persisted. Independence marked a major political turning point in the history of Spanish America, but it also left a legacy of complex socio-economic challenges that continue to resonate throughout the region. Nation-building, identity and equality remain key issues running through the contemporary history and politics of these countries.

The wars of independence in Spanish America marked an important change in the legal status of Afro-descendants, with the abolition of slavery and the recognition of equal rights in most countries. These changes were undoubtedly important legal and symbolic advances. Nevertheless, the socio-economic reality for many Afro-descendants did not match this proclaimed equality. Discrimination, racism and poverty continued to influence the daily lives of many Afro-descendants. Although free and equal under the law, they often found themselves excluded from economic and educational opportunities and marginalized in society. The transition from slavery to freedom has not been accompanied by adequate support or measures to ensure socio-economic integration. Cultural and structural barriers have persisted, preventing access to jobs, education and political office. The struggle for real equality and social justice for Afro-descendants has therefore become a long and complex undertaking, extending well beyond independence. Challenges related to race and identity continue to be relevant issues in many Latin American countries, reflecting the complex and nuanced legacy of the wars of independence on Afro-Latin American communities.

The Wars of Independence in Spanish America represented a major turning point in the lives of indigenous communities, but unfortunately, this turning point often proved tragic. Under Spanish rule, indigenous communities were often treated as legal minors, requiring the protection of the crown. Although this status entailed marginalization and restrictions, it also offered some protection against exploitation and guaranteed collective ownership of land. With independence, this protection was lifted, and the notion of equal citizenship was imposed. While well-intentioned in theory, this equality erased the legal distinctions that protected indigenous communities' rights to their land and way of life. Haciendados and small farmers often took advantage of this new situation, gradually taking over the lands previously held collectively by indigenous communities. The loss of land was not simply an economic issue; it also represented the loss of vital resources, cultural heritage, and a deep, ancestral connection with the land. Moreover, independence also brought increased pressure for assimilation. The languages, traditions and religious practices of indigenous communities were often devalued or suppressed, in an attempt to create a homogenous, "civilized" nation. The combination of land loss, exploitation and forced assimilation has had devastating consequences for many indigenous communities. Some managed to preserve their identity and way of life, often through tenacious resistance, while others were dispersed or disappeared altogether. While independence promised freedom and equality for all, indigenous communities often found themselves deprived of the protections afforded them under colonial rule, and faced with new challenges and injustices. The tragedy of this period lies in the way a struggle for freedom and equality ultimately led to marginalization and loss for some of the region's most vulnerable populations.

The wars of independence in Latin America undoubtedly marked a crucial stage in the region's history, offering the hope of a more just and equitable society. However, for Afro-descendant and indigenous communities, these changes were both a blessing and a curse, and the promise of equality remained, in many cases, unfulfilled. For Afro-descendants, independence meant the end of slavery and official recognition of their rights as citizens. It was, without doubt, a monumental victory. However, day-to-day reality often failed to match this new legal equality. Racial discrimination, latent racism and economic barriers continued to limit access to opportunity, education and well-paid jobs. Legal freedom did not necessarily mean complete emancipation from poverty and social oppression. For indigenous communities, the road to independence has been even more complex. As mentioned above, they lost the protection of the crown and collective ownership of their lands. The adoption of republican principles and the removal of racial distinctions from the law often led to land confiscation, forced assimilation and the loss of their unique cultural heritage. What was supposed to be a gesture of equality led to tragedy for many communities. These realities show that political and legislative changes are not always enough to transform the deeply rooted structures of society. Inequality and discrimination often persist despite the best intentions and surface changes. The lesson to be learned from Latin America's wars of independence is that building a truly inclusive and equitable society requires deep, ongoing work that goes beyond declarations of principle and tackles the roots of historical and contemporary injustices.

The wars of independence in Latin America represented a major turning point in the region's history, marking the end of Spanish colonial rule. However, for the enslaved, these wars did not bring the significant and immediate changes one might hope for. The abolition of slavery was uneven and often slow across the region, and post-slavery realities did not always reflect the ideals of freedom and equality promoted during the independence struggles. In some countries, such as Chile and Mexico, slavery was abolished relatively early, in 1824 and 1829 respectively. The influence of the Anglo-Saxons, who were colonizing northern Mexico, contributed to this decision, as they saw it as a way of slowing down the colonization of the northern United States. But even in these cases, the legal abolition of slavery did not necessarily mean an immediate improvement in the situation of former slaves. In most other Latin American countries, the abolition of slavery was a gradual and complex process. Many slaves remained tied to their former masters through debt systems or other forms of indentured servitude. This meant that, although legally free, they were still chained to living conditions similar to those of slavery. Nor did the abolition of slavery eliminate the problems of discrimination and racism rooted in these societies. The former slave population often continued to be marginalized and oppressed, and social and economic barriers made access to education, decent jobs and property difficult.

The abolition of slavery in Spanish America is a deeply nuanced and multifaceted chapter of history. Spanning several decades, between 1850 and 1860, this movement was not an abrupt change, but a gradual evolution, influenced by economic, political and social considerations specific to each nation. At the heart of this slow transition was the powerful slave-owning class. Anxious to preserve their economic status, these elites often advocated a gradual approach, fearing that immediate liberation would upset the economic balance. As a result, many slaves, even after proclamations of emancipation, remained shackled by debt systems or other insidious forms of servitude. The road to freedom was strewn with obstacles. Even after official abolition, discrimination, racism and poverty persisted, hindering former slaves' access to education, employment and property. Their aspiration for equality was often confronted by a very different reality. Each country in Spanish America shaped its own trajectory towards abolition, influenced by its own internal and external dynamics. Beyond the simple eradication of a practice, the abolition of slavery in Spanish America reflects the struggles and tensions of a region in the throes of metamorphosis, the echoes of which are still felt today.