« The notion of "concept" in social sciences » : différence entre les versions

| Ligne 305 : | Ligne 305 : | ||

Au niveau de l’épistémologie qui découle de cette position ontologique, il n’y a pas d’affirmation ou de vérité qui peuvent être faites, car il n’est pas vraiment possible d’acquérir un savoir scientifique qui serait vrai sans nécessiter l’investigation et les tests empiriques. Il n’y a que des positions subjectives qui résultent en des affirmations de connaissances différentes. Ensuite; l’objectif de l’analyse est de déconstruire un discours dominant et de montrer qu’il y a des voix dissonantes qui ont tout autant leur place dans la science politique et l’argumentation. | Au niveau de l’épistémologie qui découle de cette position ontologique, il n’y a pas d’affirmation ou de vérité qui peuvent être faites, car il n’est pas vraiment possible d’acquérir un savoir scientifique qui serait vrai sans nécessiter l’investigation et les tests empiriques. Il n’y a que des positions subjectives qui résultent en des affirmations de connaissances différentes. Ensuite; l’objectif de l’analyse est de déconstruire un discours dominant et de montrer qu’il y a des voix dissonantes qui ont tout autant leur place dans la science politique et l’argumentation. | ||

== | == Those who reject eclecticism (pluralism) == | ||

#''' | #'''Neomarxists''': this school interprets Marx, the objective of social science lies in the truth discovered and elaborated by Karl Marx in the 19th century and which has been updated by neomarxist authors like Nico Poulantzas and Robert Cox more recently. These societal laws discovered by Marx show that historical, economic, social and political processes, but also that human action within these structures form a whole and that history will follow a unidirectional evolutionary trajectory. This history is deterministic in the sense that Marx conceptualized this class antagonism inherent in the capitalist mode of production that will necessarily lead to the overcoming of the class system and the communist revolution. There is a rejection of eclecticism, because it is difficult to introduce new arguments into this system. One can see clear limitations in its tendency to omit other explanatory factors such as political institutions, the role of ethnicity, nationalism, the international system. To illustrate through nationalism, a Marxist would have great difficulty explaining why the German Social Democratic Party in 1914 voted the war credits in the Bundestag and allied itself by a national pact against foreign nations instead of the Social Democratic Party allying itself with all the workers of the world for a true revolution and solidarity within a social class. | ||

#''' | #'''Theorists of rational choice''': it is a lateral entry into political science through economics. The pioneers were authors such as Arrow, Anthony Downs and Mancur Olson, who were the first in the post-war period to apply economic methods and models to the analysis of political phonemes. This approach aspires to develop a unified theory, it operates by deduction from axioms or postulates derived from the economy in particular by considering the individual as a homoeconomicus, a rational being motivated by personal interest making cost-benefit calculations that try to maximize his satisfaction; postulates by which result hypotheses subjected to empirical tests. It is also a parsimonious theory because it really wants to explain political theory with very few axioms and postulates. It has a great claim to a universal applicability i.e. to be able to explain any political phenomenon and that the partial theories that it can generate in relation to defined objects can be integrated into a more general theory of politics. It is in this sense that we can speak of a rejection of eclecticism in favour of a hierarchical model and a consideration of superiority. Moreover, rational choice theory considers that it introduces a discontinuity in the sense that all that precedes it is considered prescientific. | ||

= Qu’est-ce que la science politique ? = | = Qu’est-ce que la science politique ? = | ||

Version du 22 juillet 2018 à 12:50

In social science, theory plays a central role, but it is not always clear:

- A first misunderstanding often associates theory with an abstraction, it can seem intimidating in the reserved domain of philosophers and intellectuals. Everyone, in fact, develops and uses theories.

- A second misunderstanding would be that the theory would be irrelevant, not objective and far from facts and reality.

In fact, facts and theories are closely linked through inductive and deductive theoretical reasoning:

- Inductive: this is a reasoning that starts from a few theoretical cases and attempts to identify general theoretical principles. It is starting from empirical ground and then infer principles and generalizations.

- Deductive: we start from theory, we postulate, then we deduce propositions that are necessarily deduced from logical reasoning. Mancur Olson's rational choice theory is deductive reasoning.

The theory is an explanation of how reality works. A good theory identifies the factors and processes that structure part of social reality and identifies laws to explain them.

More specifically, according to Lim, in his book Doing Comparative Politics: An Introduction to Approaches and Issues published in 2006, he defines it as a simplified representation of reality, a prism through which facts are selected, interpreted, organized and linked together so that they form a coherent whole.

The theory guides the organization of facts, it will link facts to each other. So theory not only reduces the complexity of reality, it will also order it.

Finally, the theory itself is a coherent argument characterized by a strong internal logic that will explain which mechanisms support a causal relationship.

We can think of two analogies to grasp the notion of theory:

- The pair of glasses: working the theory is like working the world through different pairs of glasses in order to focus on various aspects (role of political institutions, structure of globalized capitalism, etc.). Each pair is used to select facts. These choices are part of the theorization efforts. Thus we can focus on different aspects of reality; these focal points can complement each other.

- That of the map: the theory would be like a map, a graphic representation of the physical reality of the world essential or even indispensable in many circumstances. One can imagine maps with reliefs to for example give us an idea of world geopolitics. According to the information we will have a different representation of the world.

We usually distinguish two perspectives of explanations:

- Karl Marx's approach: he sees the explanation of theory as a way to change social reality. In the eleventh thesis on Feuerbach, Marx says: "Philosophers have only interpreted the world differently, it is now a question of transforming it".

- Max Weber's approach: Rather, he sees theory as a simple theoretical exercise that is the majority view of political science practitioners today.

Perhaps it was Marx who best formulated this approach when he said that philosophers only have to treat the world differently; today it is a question of transformation. We can clearly see the character of theory in the service of politics and social change, it is an instrument of revolution through class consciousness.

According to Robert Cox, in his book Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory[1], la théorie est toujours pour quelqu’un et dans quelques buts. Il n’est pas possible d’avoir une théorie entièrement neutre, elle est toujours au service d’une cause.

Conversely, Max Weber will emphasize the possibility of scientific objectivity in the social sciences and in particular the possibility of separating factual judgment and value judgment. In technical terms we speak of axiological neutrality according to this doctrine. The possibility of neutral and objective analysis without issuing a value judgment from the researcher is preferable.

Weber elaborates this axiological neutrality in Politik als Beruf. The following excerpt is from a series of lectures given in 1919 at the University of Munich; a reflection on the nature of scientific work is developed:

« Let us now turn for a moment to the disciplines that are familiar to me, namely sociology, history, political economy, political science and all kinds of philosophy of culture which have as their object the interpretation of the various kinds of previous knowledge. It is said, and I agree, that politics has no place in the classroom of a university. It has no place there, first of all on the student side. I deplore, for example, both the fact that in the amphitheatre of my former colleague Dietrich Schäfer from Berlin a number of pacifist students once gathered around his pulpit to make a racket, and the behaviour of the anti-pacifist students who, it seems, organised a demonstration against Professor Foerster, of whom I am, however, by my own ideas, as far away as possible for many reasons. But neither does politics have a place among teachers. Especially when they deal scientifically with political problems. Less than ever then, it has no place there. Indeed, taking a practical political position is one thing, scientific analysis of political structures and party doctrines is another. When, during a public meeting, we speak of democracy, we do not make a secret of the personal position we take, and even the need to take a clear stand is then imposed as a cursed duty. The words used on this occasion are no longer the means of scientific analysis, but constitute a political call to seek positions from others. They are no longer ploughshares to loosen the immense field of contemplative thought, but swords to attack adversaries, in short means of combat. It would be vile to use words like that in a classroom.When, in the course of an academic presentation, one proposes to study, for example, "democracy", one examines its various forms, analyses the functioning of each of them and examines the consequences that result from each of them in life; one then opposes the undemocratic forms of the political order to them; and one tries to push one's analysis to the point where the listener himself will be able to find the point from which he will be able to take a position according to his own fundamental ideals. But the real teacher will be careful not to impose on his audience, from the pulpit, any position, either openly or by suggestion - because the most disloyal way is obviously to let the facts speak. Why, basically, should we refrain from doing so? I presume that a number of my honourable colleagues will agree that it is generally impossible to put this personal reservation into practice, and that even if it were possible, it would be a hobby to take such precautions. Lady! One cannot demonstrate scientifically to anyone what one's duty as a university professor consists of. We can never demand from him that intellectual probity, which means the key obligation to recognize that on the one hand the establishment of facts, the determination of mathematical and logical realities or the observation of intrinsic structures of cultural values, and on the other hand the answer to questions concerning the value of culture and its particular contents or those concerning the way in which action should be taken in the city and within political groups, constitute two kinds of totally heterogeneous problems. If I were now asked why this last key set of questions should be excluded from an amphitheatre, I would answer that the prophet and the demagogue have no place in a university chair [...] I am ready to provide you with proof through the works of historians that each time a man of science called upon his own value judgment, there is no more full understanding of the facts »

— Max Weber, « Le métier et la vocation de savant », Le savant et le politique.

By following Weber, it is not nice to mix genres, analysis would do well to separate them and to tend them towards objectivity. However, normative considerations have their place in political science with a scientific approach that has followed the revolution of rational choice. These considerations tend to be studied in the field of political theory. There would be a division of labour in the sense of political science with again normative political theory that wonders, for example, whether parliamentary democracy is desirable. Any empirical questioning is postulated on normative postulates, however they will not be dominant, it is the dominant analysis that prevails.

Today, in practice, the vast majority of researchers are oriented towards explanatory and phenomenological research.

Max Weber on the delimitation of the field of political science and its purpose says « it is not the relationship between "things" that constitutes the principle of the delimitation of the different scientific fields, but the conceptual relationship between problems[2] ».

What delimits the object of political science are the conceptual relationships between problems, that is, between two concepts. We see that what constitutes the object is links between concepts.

The classic model

Definition: what is a concept?

As a preamble, it is useful to look at its etymology. In Latin, the word "concept" comes from "concipere" which is formed by "corp" and "capare" which means "to grasp fully". The concept will therefore be a tool, an aid to understanding.

However, there is a polysemy of the term. Different users will define it and propose various assertions:

Robert Adcock in The History of Political Science[3]

published in 2005 proposes a definition according to the classic model also called "objectivist paradigm" of the concept. He defines the concept as mental representations of categories of the world they represent external reality.

Concepts function as mental symbols ("mental symbols"; "mental representations"; "mental images"), representing external reality. This classic model treats objects as cognitive entities representing a series of classes of objects in reality via the common features of these entities in reality.

In 1984, Sartori published Social Science Concepts: A systematic analysis[4] for which the concept consists of a set of necessary characteristics that define it, thus distinguishing A from non-A. Conceptual analysis is the crucial methodological task facing any researcher. He opposes scientific discourse with the discourse of very vague common sense; Sartori requires science to define terms clearly. Definitions of clear and intersubjective concepts shared by the community as a whole must be identified. Conceptual work can also generate new concepts.

Taylor distinguishes between necessary and sufficient categories. The elements are of binary type, i.e. one has either the presence or absence of a characteristic. It is a dichotomous variable. All members of a category have the same status.

Measure

Theories establish relationships between concepts, but they remain unobservable. What can be observed are measures of conceptual abstractions. Operationalization is the link between an abstract concept and its manifestation in a specific case that translates into the creation of indicators.

A measure is a quantification of a concept. Any concept must be operationalized to be able to do empirical research and test theoretical and conceptual connections.

History and "art" of the discipline: state of the art

The five major changes that enable us to understand the state of modern political science, to define the objects of the discipline and to question the very notion of political science are :

- the shift from description/judgment to explanation/analysis: from descriptive analyses that make strong value judgements to analyses that focus on explanation and theory ;

- the rise of the method: strengthening the method and the scientific nature of research;

- specialization ;

- we leave metatheoretical approaches to theorize more with the help of mean range theories;

- the revolution in available data.

From description to explanation

Since the Second World War and from the 1960s onwards, this double movement has been observed in the study of political phenomena, from description to explanation as an object of research, but also from normative and descriptive judgment to analysis and reasoning.

Towards the end of the Second World War, political science was essentially descriptive and the question of why? was rarely asked.

In the immediate post-war period, political science was essentially normative and inhabited by reformist sentiments. Normative considerations such as "what should be" must be understood without necessarily analyzing social and political mechanisms and realities.

It is the "why? questions that allow us to go beyond the description. The answers call for an explanation based on coherent reasoning and analysis.

What piques the curiosity of researchers is recurrent empirical regularities, recurrent social facts across time and space. The objective is to try to identify the mechanisms that identify and explain these empirical regularities.

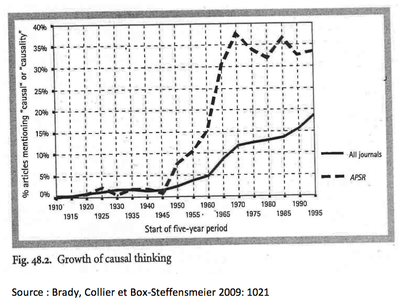

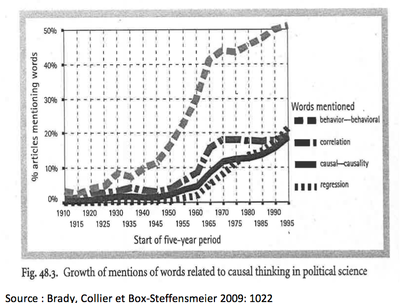

This table illustrates the number of articles that mention a word that refers to causality as "causal analyses" in the American political science journal, but also in a larger number of scientific journals. We see a strong increase in causal jargon in these publications, which illustrates this strengthening of the role of explanation in what political scientists have been doing since the 1960s.

Nota bene

Changements qui ont eu lieu sur 100 ans, mais qui se sont renforcés depuis les dernières décennies. Il y a un double mouvement dès les années 1960 :

- de la description on passe à l’explication ;

- du Jugement normatif et prescriptif, on passe à l'analyse.

- Prescriptif : jugements, évaluations émises en vue d’un aménagement politique

La science politique était très descriptive après la Seconde guerre mondiale, et très normative on ne se posait pas la question « pourquoi ? » (sentiment réformiste très présent) : c’est pourtant la réponse à « pourquoi ?» qui demande une explication et qui présuppose un raisonnement et donc une analyse.

- Accent sur l’explication et l’analyse

Les sciences politiques se rapprochent des sciences exactes: sciences physiques et sciences naturelles. (Méthode comparative : on va regarder un certain nombre de fonctions constantes)

Strengthening the method and the scientific nature of research

This emphasis on explanation goes hand in hand with greater rigour in the method. Methodological rigour and mainly a strengthening of the scientific character of research.

The compared method is based on a small number of cases from 2 to 15-20. This method is scientific because if we look around us, we see a great diversity of political institutions Switzerland and characterized by federalism while the French state is highly centralized, others by Switzerland has a parliamentary system while in France the political and semi-presidential regime.

There is great institutional and political diversity across the world and this variation makes comparison desirable for two main reasons:

- the comparison gives us a good insight into the realm of the possible, it opens our eyes to the great institutional varieties that exist throughout the world reflecting the possible options and the capacity that societies have to choose their destiny. We see that there is a freedom that exists to shape its institutions through history, culture, society, etc. Effective institutions exist elsewhere and could be introduced in one's own country.

- Institutional and political differences are an analytical point for testing causal hypotheses, because causal analysis requires institutional, political, economic variation between entities being compared. These disputes will provide analytical support that will allow causal type explanation.

In comparative politics, "most similar research design" is a research design that will compare countries that are the most similar to each other. The idea is to identify an explanatory independent variable as an institution or political practice or even an individual characteristic of the voter if one is interested in electoral behaviour; identify such an independent variable, an explanatory variable absent in one of the two cases, but present in the other and that it is associated with different results at the level of the explained variable.

The selected cases are similar in all respects except for one independent variable and the result.

Bo Rothstein's article Labor-market institutions and working-class strength published in 1992[5]

which illustrates the theme of the institutions will focus on about fifteen European OECD countries, these are countries that are very similar from a geographical, historical, economic point of view. He will show on the basis of the trade union organization of the workers that there are very great variations in the European countries; he seeks to explain the variation. For this he will be looking for a factor that varies to explain this difference: a main institutional variable that will be the Gantt system, some countries experience such an institution of the labor market unlike others which will explain to a large extent why Scandinavian countries have high unionized rates.

In other words, these countries are very similar in many respects, but one variable changes which will explain the level of union density.

A second article by Robert Cox compares a smaller number of countries, namely the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark, on the reform capacity of the welfare state based on a most similar research model.

We can also illustrate the strengthening of the method by the increasing use of regression analysis in political science that comes from econometrics.

In this table, we see a growth of this statistical tool in the causal demonstrations that political scientists make more and more from the middle of the century. Thus, can isolate the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable while controlling the effects of an alternative variable. If we use the explanations of the Weimar Republic, if we took more countries and historical moments, we would be interested in isolating the effect of a single variable on the fall of the Weimar Republic, which could for example be the proportional system. The idea is to isolate this net effect, that is, how important one variable is over another, which is what regression analysis allows.

Nota bene

Avantages de la comparaison :

- Elle donne un bon aperçu du domaine du possible : options possibles et capacités de la société de choisir pour les sociétés. Elle nous rencontre la plasticité des institutions politiques.

- Différences institutionnelles et politiques offrent un point d’appui analytique à fin déterminer des hypothèses de type causal. Car l'analyse causale requiert de la variation institutionnelle, politique et sociale entre pays qui se comparent les uns aux autres. Fournit « analytical leverage »

Most similar research design: l'idée c'est d'identifier une variable indépendante (facteur explicatif) de l'objet qu'on souhaite expliquer dont l’absence et sa présence dans différent cas va être associé à des résultats différents.

Donc la sélection de cas des pays se fait sur la similarité des cas.

Les pays vont être le plus comparables possible à l’exception de la variable indépendante. Postulé comme le facteur explicatif principal. Et la variable dépendant (résultat) va aussi varier.

Specialization in the field

Great thinkers such as Marx, Weber, Darwin, Tolstoy, Dickens or Dostoevsky were each a living encyclopedia on their own. A few years ago, Foreign Policy magazine conducted a ranking of the 100 most influential international thinkers, including Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, Maria Vargas, Joe Stiglitz and Martin Wolf, an influential journalist with the Financial Times.

One may wonder why the contemporary list is so unimpressive:

- it takes a certain distance in time to truly judge the genius;

- this proximity, and thus familiarity with the great thinkers of our times, reduced genius tending to trivialize it;

- a structural change in the way knowledge is managed, in particular universities promote excessive specialisation; knowledge progresses through cooperation and interaction between specialists organised in networks which meet at international colloquia and which increasingly occupy niches and perimeters of smaller knowledge and which nevertheless accumulate and grow in knowledge. This is facilitated by new technologies such as the Internet that allow all kinds of cooperation around the world. This specialization is reflected in the organization and structures of political science departments, particularly at the University of Geneva, where professors occupy chairs covering areas of the sub-discipline of political science. One and the same researcher tends to contribute to a single subfield of political science. For example, Damian Raess is an expert in comparative politics.

Mid-range theories

Nowadays, we tend to leave aside the big"-isms" like Marxism, liberalism, constructivism, realism in order to focus on context-specific debates and theories of averages. These are context- and problem-specific debates that can also be solved through empirical analysis.

Metatheory

A metatheory is a framework or schema that logically connects and reintegrates partial theories and participates in the construction of a general theory. It is a general theory of politics, which seeks to show how these various theories entwine.

These are, for example, structuralism, Marxism, historical-institutionalism or the theory of rational choices.

Mid-range theories

The definition comes from Robert Merton, he speaks of a theory with limited scope that focuses on one or a limited number of political aspects that tend to be specific to an issue. Researchers, for example, will dedicate their entire careers to better understanding the theorizing processes. It is a set of theories of limited scope that will try to explain specific phenomena, for example, specialists in civil conflicts who will try to analyze their determinants. It is also the theory of electoral behaviour and the approach of the varieties of capitalism that attempt to analyse, among other things, the results in the way market economies are organised between countries.

Revolution in available data

This revolution can be mentioned in quantitative data and the availability of large data banks and opinion polls that facilitate and enable research for political scientists and allow international comparison. It is a factor that contributes to the strengthening of quantitative and statistical analysis in our discipline.

History of the discipline: theories and conceptions

The constitution of the discipline, its professionalization and empowerment dates back about 100 years, it is a young discipline. However, its origins can be traced by a set of texts dating back to ancient Greece.

Origins in Ancient Greece

In the 5th century BC, Greece is a world where the analysis of political ideas and ideals, the properties of political systems, the essence of citizenship and government action as well as state interventions in the political and foreign policy spheres are studied recurrently.

- Plato (427-347 BC) The history of political science begins with Plato. In The Republic which is the first classic in the discipline, key work that offers the first political typology of different regimes.

- Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) Politics. He pursued an inductive, empirical and historical method of social observation that contrasted with Plato's deductive reasoning and idealism.

There are two major themes dear to political science in this period:

- What are the institutional forms of politics?

- What are the criteria that will make it possible to evaluate these various institutional forms? This is a typically normative debate.

Renaissance

The Middle Ages are dominated by Christian thinkers and the theory of natural law is the belief in a universal natural law resulting from an order of transcendence of the divine; therefore the city-state must implement structures responding to this natural law. It is from the rebirth that things change.

- Machiavelli [1469 - 1527] : "The Prince" is a treatise on the legitimacy of regimes and politicians. He sees in morality not only an end in itself as is the case in Christian thought, but he will say that in politics morality is also a means to a certain end. Morality is an instrument that allows a certain purpose.

- Jean Bodin [1529 - 1596] : he is a theoretician of state sovereignty, his main work is The Six Books of the Republic from which he exposes the nature of the state whose existence is defined by the notion of sovereignty.

With the Enlightenment progress, contributions in theory accelerated with Hobbes, Locke, Humes, Smith, but also Hamilton in the Anglo-Saxon tradition. In the French tradition we can note Montesquieu and his work''De l'Esprit des Lois'' which became famous for the distinction he drew between legislative, executive and judicial power with the notion of separation of powers.

Late 18th - 19th century

This is the period of the classics of social theory:

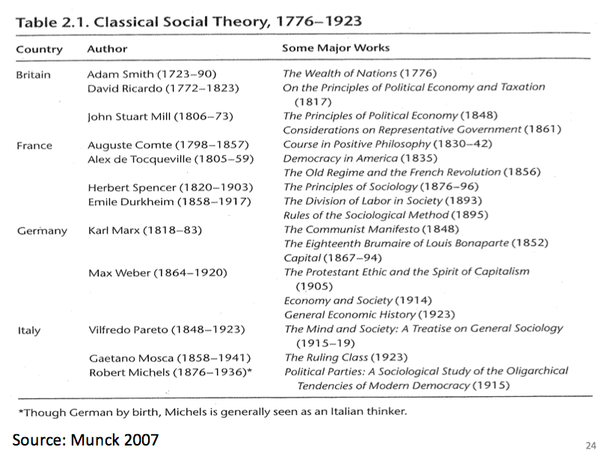

19th century: Classical period of social theory

On the one hand, political philosophy is marked by a certain historical determinism, particularly in the work of Engels and Marx, who consider history as a linear development in the direction of freedom and reason.

In reaction to these determinisms there is a first wave of empirical work which will see the light of day and oppose these abstract, generalizing and deterministic theories proposed in the middle of the 19th century.

This reaction produces a large number of descriptive studies of political institutions, including The State: Elements of Historical and Practical Politics by President Wilson which is a political ethnography of political institutions with a classification of models with a similar typology developed by Plato and Aristotle.

Wilson was a Democratic president during the First World War period, he himself was trained as a political scientist at Princeton University writing many books in political science.

Weber and Durkheim contrast modern rationality with tradition. They address the themes of modernisation, economic development, social development and also political development which is democratisation in particular.

These themes are still key themes in political science today.

It is becoming more and more common to speak of the study of politics as a true science. There is a definite advance in the scientific rigour of the analysis of political facts, greater coherence in the reasoning and proposals put forward are increasingly generated by the inductive approach rather than on presuppositions of human nature as in the Middle Ages.

An increasing use of the comparative method is emerging, but it remains in an embryonic and unsystematic state.

Political science has as its main object the institutional sciences of government and therefore always adopts a very descriptive approach of a legal and formal type. Focusing on these formal institutions of governments and parliaments, it remains committed to a narrow research agenda.

Fin du XIXème début du XXème

Au début du XXème siècle, la discipline qui va se professionnaliser. C’est dans ce contexte que la science politique comme discipline se professionnalise et s’autonomise ; ce processus a lieu d’abord aux États-Unis avec la création des premiers départements de science politique :

- en 1880, on peut noter la création de la première école doctorale à la Colombia University de New York ;

- en 1903 a été fondée l’association américaine de sciences politiques qui a rassemblé des chercheurs en science politique aux États-Unis.

On a une différentiation par rapport à l’histoire qui est la discipline la plus étroitement associée à la science politique dans ces années :

- « History is past politics, and politics is present history[6] » : la science politique va se concentrer sur la période contemporaine et va traiter des changements dans les dernières décennies.

- Elle va aussi rejeter l’histoire dans l’ambition qu’elle a d’adresser l’ensemble des facteurs explicatifs et de fournir une explication unique d’un phénomène donné. Pour les historiens, tout évènement a une explication unique qui n’est pas reproduite plus tard, avant, ailleurs dans le monde alors que la science politique va se concentrer sur un nombre plus restreint de facteurs et va formuler des propositions de type générales qui sont valables à travers l’espace et le temps.

Les limites approchent de types formels, légales et descriptives amenant des propositions et des hypothèses. Les propositions sont de plus en plus générées par une approche empirique. L’analyse comparée demeure à un état embryonnaire, peu développée encore.

Selon la devise de l’époque : la science politique se concentre sur la période contemporaine et l’histoire sur le passé. La science politique se centre sur des facteurs limités (de types uniques) ; par contre, l'histoire est trop ouverte.

Révolution behaviorale de l’après-guerre

En anglais, « behavior » veut dire « comportement ». C‘est la révolution comportementale c’est-à-dire que l’on va se focaliser sur l’étude des comportements politiques des acteurs. Elle s’initie d’abord avec l’École de Chicago.

- École de Chicago [1920 - 1940]

Fondée par Charles Merriam à l’Université de Chicago en 1921. En 1929, Merriam publie un manifeste pour une nouvelle science politique qui cherche à rompre avec l'approche historique. Ce manifeste va engendrer un vif débat pour définir la science politique et saisir les nouvelles tendances. L’École de Chicago va émerger comme un centre important d’ébullition politique.

D’autres protagonistes sont Harold Lasswell ou encore Leonard White en administrations publiques ou encore Quincy Wright en relations internationales.

Les objets qui les intéressent sont l’étude des comportements de vote et l’étude de la mobilisation sociale en politique. En 1939, Lasswell va co-publier une étude sur l’impact de la grande dépression de 1929 sur les capacités de mobilisation politique des chômeurs dans la ville de Chicago intitulée World revolutionary propaganda. A Chicago study[7].

Pour résumer, la signification de l‘École de Chicago réside dans une démonstration qu’une véritable amélioration de la connaissance politique est possible par des études empiriques rigoureuses et par l’utilisation de méthodes plus sophistiquées qui sont au cœur des attitudes et des comportements individuels.

Révolution behaviorale de l’après-guerre [1950 - 1960]

C’est le moment charnière de la révolution behaviorale qui est porteuse de deux idées principales :

- les objets de la science politique : les tenants de ces courants s‘opposent à une définition des limites de la science politique qui serait restreinte aux institutions formelles de gouvernements. Ils cherchent à dépasser les institutions formelles des gouvernements et à intégrer des procédures informelles et des comportements politiques que ce soit d’individu ou des groupes comme les partis politiques. Les procédures informelles pourraient être des procédures pour mettre sur pied des nouvelles politiques publiques, il y a souvent des consultations de groupes d’intérêts organisés comme les syndicats ainsi que d’autres associations de la société civile. Ils ne sont pas toujours institutionnalisés, ce n’est pas une institution formelle, mais plutôt que l’on pourrait caractériser d’informelle.

- volonté de rendre la science politique plus scientifique au niveau de la méthode : ils s’opposent à l’analyse empirique qui n’est éclairée par la théorie et vont prôner un raisonnement théorique rigoureux et systématique par des tests empiriques notamment des études d’hypothèses théoriques.

Notons la croissance rapide de l’activité de la recherche académique dans l’après-guerre ; les sous-disciplines de la science politique que sont les relations internationales, la politique comparée et l’étude des institutions américaines s’institutionnalisent, occupent un espace visible, de nouvelles sous discipline viennent s’ajouter à dessous-disciplines existants comme, par exemple, le début des études de security studies, des relations économiques internationales, mais aussi l’étude des comportements politiques.

Un autre acteur va être le fer-de-lance de la révolution behaviorale est l’Université de Michigan qui va rependre la culture scientifique dans l’après-guerre.

Deux ouvrages de cette période et qui incarnent cette révolution behaviorale sont Political Man; the Social Bases of Politics de Lipset publié en 1960[8] et The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations publié en 1963 de Gabriel Almond et Sidney Verba[9].

Pour conclure, la révolution behaviorale a amené une plus grande orientation théorique, un renforcement des raisonnements théoriques et une plus grande sophistication théorique dans la discipline. En d’autres termes, c’est une considération plus sérieuse de la méthode scientifique.

Troisième révolution scientifique [1989 - ]

À partir des années 1970 va avoir lieu une troisième révolution scientifique qui est un prolongement de la révolution behaviorale dans le sens où elle va continuer à affirmer et à vouloir toujours une plus grande rigueur de l’aspect scientifique de la discipline.

La Théorie du choix rationnel [TCR] est une théorie qui repose sur des postulats empruntés de la science économique comme les postulats de l’homo-economicus qui va faire des choix en fonction des coûts et de bénéfices afin de maximiser son utilité. D’autre part, elle ne cherche pas à redéfinir ce que sont les objets de la science politique, mais elle va avancer une théorie générale de l’action sous forme de métathéorie.

Cette révolution scientifique va mettre l’accent un raisonnement logique ultra vigoureux dans la théorie et notamment les raisonnements de type formel ou on pose des postulats au début de l’analyse et dont on va déduire par un raisonnement cohérent et logique un certain nombre de propositions et d’hypothèses que l’on va tester empiriquement. C’est également la théorie des jeux et au niveau des méthodes elle va pousser la rigueur par l’analyse statistique.

Elle va avoir des répercussions sur d’autres approches théoriques et méthodologiques notamment la méthode qualitative, en réaction à la pression des théoriciens du choix rationnel, la méthode qualitative va elle se renforcer et devenir plus rigoureuse. On constate un effet de spill-over sur les autres méthodes :

- King, Keohane, Verba 1994. Designing Social Inquiry : Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research[10] ;

- Brady & Collier 2004. Rethinking Social Inquiry : Diverse Tools, Share Standards[11] ;

- George & Bennett 2005. Case Study and Theory Development[12] ;

- Gerring (2007) Case Study Research: Principles and Practices[13].

En guise de synthèse de ce survol, on peut résumer quelques-uns de ces grands paradigmes par une idée simple parce que chacune de ces approches a une maxime qui résume assez bien les contributions faites parla théorie du behavioralisme et du choix rationnel :

- behavioralisme : « don’t just at the formals rules, look at people actually do », il ne faut pas seulement se concentrer dans l’analyse a des institutions formelles mas il faut aussi s’intéresser à des règles et des procédures informelles et tout particulièrement la manière dont les individus agissent au sein de ce cadre.

- choix rationnel : « always remember people push you power and interest », ce qui motive les décisions des individus c’est leurs considérations et leur quête de pouvoir et de satisfaction maximale selon la terminologie néoclassique.

Deux autres grandes écoles qui peuvent être amassées en idées simples :

- systémisme : « all, everything is connected, feedback matter », tout est connecté, mais seul le feed-back compte, car il crée des résultats et des outcomes qui vont être intégrés aux nouvelles demandes produites et adressées au système politique

- structuralisme-fonctionnalisme : « forms fits functions », la fonction va déterminer la forme que prennent les institutions politiques.

Finalement, l’autre idée qui définit l’institutionnalisme.

- institutionnalisme : « institutionalism matter », tout un courant de l’institutionnalisme-historique a émergé qui se défini par rapport à cette idée-là.

Ce compte rendu de l’histoire disciplinaire est celui de la « perspective progressiste-éclectique » définie par Almond que l’on peut définir comme le courant dominant de la science politique. Il n’est pas partagé unanimement, mais par ceux qui l’acceptent comme critère du savoir et de l’objectivité avec cette possibilité de séparer les faits des valeurs qui est basée sur les règles de preuve empirique :

- « Progressiste » dans le sens d'impute de la notion de progrès de la science historique d’accumulation de savoirs, soit quantitativement c’est-à-dire en termes du nombre de connaissances accumulées dans le temps soit qualitativement dans la rigueur et le progrès de la connaissance.

- « Éclectique » dans le sens de non hiérarchique, d’un pluralisme intégratif c’est-à-dire qu’il n’y pas un courant qui va se considérer comme supérieur à d’autres, c’est intégratif dans le sens ou toute perspective et méthodologie peut faire partie de cette perspective et histoire dominante. Mais la théorie du choix rationnel et l’institutionnalisme vont produire des travaux qui vont s’intégrer dans cette perspective.

Ces tableaux récapitulent l’histoire de la discipline avec les différentes révolutions et les classifications, on voit aussi l’évolution des méthodes à travers le temps.

Histoires alternatives

Comme cette histoire n’est pas unanime, il convient de citer d’autres écoles

Courants qui rejettent le caractère scientifique et progressiste

- Antiscience : cette position est associée à Lévi-Strauss, il réfute l’héritage de Weber qui est séparation entre faits et valeurs et cette possibilité d’objectiver la réalité sociale ; il réfute aussi le behavioralisme et de manière plus générale le positivisme c’est-à-dire l’étude causale en science politique à travers l’analyse rigoureuse empirique. Cette position estime que l’introduction de la méthode scientifique est nuisible, car elle est une illusion, de plus elle obscurcit et rend triviale la dynamique sociale. Lévi-Strauss propose une science sociale humaniste qui soit intimement et passionnément engagée dans un dialogue avec les grands philosophes et les grandes philosophies à propos du sens des idées centrales de la science politique. C’est une posture qui propose une interprétation des faits sociaux plutôt qu'une explication et qui voit dans la méthode scientifique une illusion.

- Post-science (certains constructivistes ; postmodernistes) : c’est une position post-behaviorale et post-positiviste illustrée parle philosophe Jacques Dérida avec l’idée de déconstruction plaçant ce courant comme postmoderniste. Similairement à la position antiscience il réfute l’opposition entre jugement de faits et jugement de valeurs en adoptant une position critique. Il veut la fin du positivisme et de l’exigence de la vérification empirique comme seule position philosophique dans les sciences humaines. Il y a une exigence de vérification empirique d’une théorie qui va amener à l’avancée de la science, ce que les post-sciences réfutent en prônant un renouvellement du discours normatif en réintroduisant les valeurs.

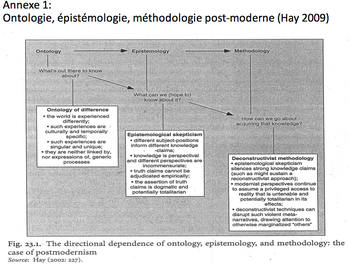

Toute perspective théorique est associée à des choix fondamentaux :

- Ontologie : fait référence à la nature du monde social et politique donc à ce qui « est ». Elle consiste en un ensemble de postulats et d’affirmations que chaque approche théorique fait par rapport à la nature de la réalité sociale c’est-à-dire par rapport à ce qui existe, mais aussi par rapport à l’entité ou l’unité de base que constitue le politique ou l’analyse du politique.

- Épistémologie : fait référence à ce que nous pouvons connaitre du monde social et politique.

- Méthodologie : fait référence à la procédure qui nous permet d’acquérir la connaissance.

Par rapport à ce qui « est » on peut voir une distinction entre les postmodernes et le courant dominant progressiste-éclectique dans le sens où ce dernier adopte une ontologie objective soit la réalité, c’est-à-dire ce qui « est », existe indépendant de la conception que l’on peut en avoir. Dès lors, la réalité peut être distinguée de sa représentation. Les postmodernes adoptent une ontologie subjective dans le sens ou la réalité ne peut pas être distinguée de sa représentation et/ou la représentation que l’on a du monde constitue le monde.

Ce tableau résume la position ontologique, épistémologique et méthodologique caractéristique de l’école postmoderne.

Au niveau de l’épistémologie qui découle de cette position ontologique, il n’y a pas d’affirmation ou de vérité qui peuvent être faites, car il n’est pas vraiment possible d’acquérir un savoir scientifique qui serait vrai sans nécessiter l’investigation et les tests empiriques. Il n’y a que des positions subjectives qui résultent en des affirmations de connaissances différentes. Ensuite; l’objectif de l’analyse est de déconstruire un discours dominant et de montrer qu’il y a des voix dissonantes qui ont tout autant leur place dans la science politique et l’argumentation.

Those who reject eclecticism (pluralism)

- Neomarxists: this school interprets Marx, the objective of social science lies in the truth discovered and elaborated by Karl Marx in the 19th century and which has been updated by neomarxist authors like Nico Poulantzas and Robert Cox more recently. These societal laws discovered by Marx show that historical, economic, social and political processes, but also that human action within these structures form a whole and that history will follow a unidirectional evolutionary trajectory. This history is deterministic in the sense that Marx conceptualized this class antagonism inherent in the capitalist mode of production that will necessarily lead to the overcoming of the class system and the communist revolution. There is a rejection of eclecticism, because it is difficult to introduce new arguments into this system. One can see clear limitations in its tendency to omit other explanatory factors such as political institutions, the role of ethnicity, nationalism, the international system. To illustrate through nationalism, a Marxist would have great difficulty explaining why the German Social Democratic Party in 1914 voted the war credits in the Bundestag and allied itself by a national pact against foreign nations instead of the Social Democratic Party allying itself with all the workers of the world for a true revolution and solidarity within a social class.

- Theorists of rational choice: it is a lateral entry into political science through economics. The pioneers were authors such as Arrow, Anthony Downs and Mancur Olson, who were the first in the post-war period to apply economic methods and models to the analysis of political phonemes. This approach aspires to develop a unified theory, it operates by deduction from axioms or postulates derived from the economy in particular by considering the individual as a homoeconomicus, a rational being motivated by personal interest making cost-benefit calculations that try to maximize his satisfaction; postulates by which result hypotheses subjected to empirical tests. It is also a parsimonious theory because it really wants to explain political theory with very few axioms and postulates. It has a great claim to a universal applicability i.e. to be able to explain any political phenomenon and that the partial theories that it can generate in relation to defined objects can be integrated into a more general theory of politics. It is in this sense that we can speak of a rejection of eclecticism in favour of a hierarchical model and a consideration of superiority. Moreover, rational choice theory considers that it introduces a discontinuity in the sense that all that precedes it is considered prescientific.

Qu’est-ce que la science politique ?

On peut distinguer notamment trois définitions classiques de la politique :

- Lasswell publie en 1936 Politics: Who Gets What, When, How[14] où il définit la science politique comme qui obtient quoi, quand et comment. En d’autres termes il s’agit du conflit permanent au niveau de la société pour le contrôle des ressources rares. Ce sont des conflits entre individus et entre groupes sociaux pour s’octroyer les ressources d’une société qui sont forcément limitées. Cela fait référence à des conflits autour de la redistribution des ressources rares dans une société.

- Goodin publie en 2009 l'ouvrage The State of the Discipline, The Discipline of the State[15] pour qui la politique est l’utilisation limitée du pouvoir social qui serait présenté comme l’essence du politique. Le concept central est la notion de pouvoir qui fut notamment très travaillé en sciences sociales. Selon Weber, le pouvoir de A sur B, c’est la capacité de A d’obtenir que B fasse quelque chose qu’il n’aurait pas fait sans l’intervention de A. Cette définition générale renvoie à la capacité d’agir sur d’autres individus ou groupe ou États en contraignant leurs comportements sans cette intervention. Un des intérêts de cette définition est de montrer que le pouvoir est relationnel. Pour Goodin, le pouvoir va prendre de très nombreuses formes, mais il sera toujours contraint, car même les plus puissants ne peuvent pas imposer par la contrainte, leur vouloir aux dominés. Le pouvoir prend de nombreuses formes, mais il est toujours contraint et c’est la tâche de la science politique de rendre compte de ces relations de pouvoir à différents niveaux.

- Goodin propose une autre définition comme quoi la science politique est la discipline de l’État. Ici, l’État est compris comme un ensemble de normes, d’institutions et de relations de pouvoir. En ce qui concerne les normes,l’histoire de l’État moderne est étroitement liée à la démocratie libérale, il y a des normes spécifiques qui peuvent être par exemple la séparation des pouvoirs, mais aussi sur l’idée de compétition politique, mais reposent tout comme sur la participation politique de chaque individu et la responsabilité politique des élus envers les électeurs. Ce sont tout un ensemble de normes et de valeurs qui doivent être élaborées et justifiées, et en pourquoi la supériorité de ces valeurs relève d’une considération normative. L’État est un ensemble d’institutions, ce sont les différentes formes du politique, mais aussi à l’intérieur d’un type de régime ; c’est l’opération ou le fonctionnement des institutions démocratiques, des différents types de régimes. L’État serait comme le site privilégié des rapports de pouvoirs entre individus, entre groupes.

La science politique s’autonomise au cours du XXème siècle, notamment vis-à-vis de l’histoire. James Duesenberry (1918 – 2009), économiste américain était professeur d’économie à Harvard disait « l’économie ne parle que de la façon dont les individus font des choix, la sociologie ne parle que du fait qu’ils n’ont aucun choix à faire »[16]. On voit que la sociologie est de pair avec une conception de l’homme sursocialisé, l’agir renvoi aux forces sociales externes avec une marge de manœuvre limitée alors que l’économie néoclassique a une conception de l’homme sous-socialisé ou l’individu opère dans la sphère économique qui est distincte et séparée des autres domaines de la vie sociale.

On peut d’autre part citer Marx « les hommes font leur propre histoire, mais ils ne la font pas arbitrairement dans les conditions choisies par eux, mais dans les conditions directement données et héritées du passé. La tradition de toutes les générations mortes pèse d’un poids très lourd sur le cerveau des vivants. Et quand même il semble occupé à se transformer, eux et les choses à créer quelque chose de tout à fait nouveau, c’est précisément à ces époques de crise révolutionnaires qu’ils évoquent craintivement les esprits du passé, qu’ils leur emprunte leurs noms, leurs mots d’ordre, leurs costumes pour apparaitre sur la nouvelle scène de histoire sous ce déguisement respectable et avec ce langage emprunté »[17].

On voit la tension dans le développement historique qui est pris entre l’agir humain dans des structures et des institutions, mais ne la font pas arbitrairement dans des conditions choisie par eux, mais dans des conditions données et héritées du passé.

Annexes

References

- ↑ Cox, Robert W.. "Beyond international relations theory: Robert W. Cox and approaches to world order", Approaches to World Order. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. 3-18.

- ↑ M. Weber, Essais sur la théorie de la science, op. cit. p.146

- ↑ Adcock, R. and Bevir, M. (2005), The History of Political Science. Political Studies Review, 3: 1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-9299.2005.00016.x

- ↑ Social Science Concepts: A Systematic Analysis Giovanni Sartori Beverley Hills: Sage, 1984

- ↑ Rothstein, B. (1992). ‘Labor-market institutions and working-class strength’. In S. Steinmo, K. Thelen and F. Longstreth, eds. Structuring Politics. Historical Institutionalism in Com¬parative Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 33–56

- ↑ Herbert Baxter Adams (1883). The Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science . p. 12.

- ↑ Lasswell, Harold Dwight, and Dorothy Blumenstock. World Revolutionary Propaganda: A Chicago Study. New York: Knopf, 1939.

- ↑ Lipset, Seymour Martin. Political Man; the Social Bases of Politics. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1960.

- ↑ Almond, Gabriel A., and Sidney Verba. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1963.

- ↑ King, Gary/ Keohane, Robert O./ Verba, Sidney: Designing Social Inquiry. Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton University Press, 1994.

- ↑ Henry E. Brady & David Collier (Eds.) (2004). Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards. Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 362 pages, ISBN 0-7425-1126-X, USD 27,95

- ↑ Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences Alexander George, Andrew Bennett Cambridge, USA Perspectives on Politics - PERSPECT POLIT 01/2007; 5(01):256. DOI:10.1017/S1537592707070491 Edition: 1st Ed., Publisher: MIT Press, pp.256

- ↑ Case Study Research: Principles and Practices. John Gerring (Cambridge University Press, 2007). doi:10.1017/S0022381607080243

- ↑ Lasswell, Harold Dwight, 1902- Politics; who gets what, when, how. New York, London, Whittlesey house, McGraw-Hill book Co. [c1936] (OCoLC)576783700

- ↑ Goodin, R 2009, 'The State of the Discipline, The Discipline of the State', in Robert E. Goodin (ed.), Oxford Handbook of Political Science, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 3-57.

- ↑ Duesenberry, 1960, p. 233

- ↑ Karl Marx (trad. R. Cartelle et G. Badia), éd. sociales, coll. Classiques du marxisme, 1972, chap. Les origines du coup d'État du 2 Décembre, p. 161