« 海地革命及其对美洲的影响 » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

(→地区差异) |

||

| Ligne 65 : | Ligne 65 : | ||

== 地区差异 == | == 地区差异 == | ||

1789 年,圣多明各殖民地的人口差距惊人,绝大多数居民生活在奴隶制的枷锁之下。88%的人口沦为奴隶,殖民地的经济基本上依赖于强迫劳动。广袤的农田反映了圣多明各的经济活力。甘蔗、咖啡、蓝靛和其他经济作物种植园推动了殖民地的经济发展。它们也是奴隶的主要雇主。这些规模庞大的劳动密集型农场需要大量工人来经营。大部分奴隶人口都集中在这些地区。这些从非洲输入的奴隶为种植园提供了劳动力,使殖民地成为西印度群岛的主要经济大国,并为法国本土创造了巨额利润。奴隶集中在经济作物区不仅是经济上的需要,也塑造了殖民地的社会地理。种植园本身就是一个社区,有自己的等级制度和社会动态,其核心是残酷的奴隶制。然而,奴隶高度集中在关键地区也给统治精英带来了风险。奴隶的接近和数量增加了叛乱和暴动的可能性,鉴于殖民地日益紧张的局势和明显的社会不平衡,这种担忧并非毫无根据。这些紧张局势最终爆发,引发了海地革命,这是美洲历史上最重要的革命之一。 | |||

圣多明各 "北部平原 "是殖民地经济机器跳动的心脏。这个肥沃的地区沐浴在有利的热带气候中,农业活动十分活跃,主要集中在甘蔗的种植上,甘蔗是殖民地的苦乐财富。甘蔗的利润无与伦比。甘蔗转化为蔗糖和朗姆酒带来了可观的附加值,这促使殖民者对这种作物进行大规模投资。然而,这种盈利能力是以巨大的人力成本为代价的。甘蔗的种植、收割和加工过程既繁重又劳累。这需要大量劳动力,因此该地区奴隶高度集中。北部平原的种植园规模宏大,组织严密。它们包括一眼望不到边的田地、压榨甘蔗的磨坊、蒸煮甘蔗汁和生产蔗糖的烤箱,以及酿造朗姆酒的蒸馏器。但在经济效益的表象背后,却是残酷的现实。这些种植园里的奴隶要在热带烈日下长时间从事艰苦的工作,几乎没有休息时间,而且随时可能受到严厉的惩罚。蔗糖种植的狂热节奏和要求也产生了社会影响。奴隶高度集中在北部平原导致了复杂的社会动态,不同的非洲文化在这里共存、融合,并创造了新的文化表达和抵抗形式。正是在这一地区,渴望自由和正义的奴隶们点燃了海地革命的第一束火花。 | |||

圣多明各东南部的土地虽然与北部平原一样肥沃,但主要种植甘蔗以外的作物。可可和蓝靛是这一地区的宝藏。用于生产巧克力的可可是一种珍贵的作物,在欧洲市场上非常抢手。可可豆经过收获、发酵、烘干和烘烤后,被加工成巧克力,这就是后来风靡全球的巧克力。可可种植园的工作条件虽然不如甘蔗园那么紧张,但仍然十分严格,奴隶们负责从种植到收获的所有工作。蓝靛则是一种染料植物。经过发酵和加工,靛蓝的叶子会产生一种受人追捧的蓝色,用来给织物染色。这种蓝色在欧洲备受推崇,圣多明各的蓝靛以其高品质而享有盛誉。与可可一样,靛蓝的生产也需要专门的劳动力,虽然生产过程与甘蔗不同,但仍然需要对奴隶进行劳动密集型的剥削。虽然人们经常强调北部平原在殖民地经济中的突出作用,但东南部地区及其可可和蓝靛作物也是重要的经济支柱。不同地区的社会互动就像作物本身一样各不相同,但不变的是殖民地对奴隶劳动的依赖,没有奴隶劳动,圣多明各的富裕是不可想象的。 | |||

到 18 世纪末,圣多明各的社会和经济结构清楚地反映了殖民制度的需要和要求。殖民地丰富的财富来自种植园,而种植园的位置在很大程度上影响着人口的分布。甘蔗是殖民地的主要经济作物,种植和加工都很密集。从种植到最后加工成糖和朗姆酒,都需要大量工人。因此,甘蔗种植园丰富的北部平原是奴隶最集中的地方。一望无际的甘蔗田每天都是劳作的场景,糖厂里到处都是将甘蔗加工成原糖和朗姆酒的奴隶。在东南部,虽然奴隶的数量相对较少,但他们对靛蓝和可可的种植至关重要。这一地区的种植园也需要专门的劳动力。奴隶们日出而作,日落而息,负责种植、收割、发酵和加工这些珍贵的作物。在农业区之外,奴隶集中在开普敦和太子港等城市地区,他们在那里充当佣人、工匠,或在码头和仓库工作。因此,圣多明各的人文地理与其经济地理密切相关。哪里对某种作物有需求,哪里就会有大量的奴隶来满足这种需求。这种结构遗留下来的悲哀是,尽管圣多明各是世界上最富有、最多产的殖民地之一,但这种繁荣是建立在被奴役、被剥夺权利和自由的人民的基础之上的。 | |||

圣多明各残酷的剥削制度为反抗和起义提供了肥沃的土壤。北部平原和东南部尽管表面上富庶,但背后却是社会的火药桶。对比十分鲜明。一方面,富裕的种植园主和商人生活相对奢侈,享受着强迫劳动的成果。另一方面,奴隶们却忍受着难以想象的痛苦,生活条件恶劣,如果辜负了主人的期望,就会受到残酷的惩罚。奴隶因简单的违法行为而受到严厉惩罚是司空见惯的事,基本权利的缺失更加剧了他们的绝望。家庭支离破碎,文化和传统遭到残酷压制,任何反抗或抗议的企图都会受到严厉惩罚。然而,在这种压迫的阴影下,开始出现了一些微妙的反抗形式。奴隶们利用宗教,特别是伏都教,不仅寻求精神慰藉,还将其作为团结社区的工具。伏都教仪式成为奴隶们远离主人视线、聚集和组织起来的场所。随着时间的推移,日益增长的不满情绪和集体意识催生了采取行动的愿望。有关法国大革命以及平等、自由和博爱理想的信息在奴隶中传播,给他们带来了希望和鼓舞。1791 年的海地革命将这些紧张局势推向了高潮。北部平原成为这场革命的中心,成千上万的奴隶在图森-奥维杜尔等标志性人物的领导下,拿起武器反抗压迫者。这场始于奴隶起义的革命很快演变成一场全面的革命,最终于 1793 年废除了奴隶制,海地最终于 1804 年获得独立。因此,这片曾经是奴隶制残暴象征的土地成为了世界上第一个自由黑人共和国的诞生地,也是历史上最成功的奴隶制革命的发源地。 | |||

奴隶集中在圣多明各最繁华的地区,如北部平原和东南部,这不仅仅是人口上的巧合,而是对起义的动力起了至关重要的作用。地理上的接近使奴隶们能够建立联系、交流信息,并在面对压迫时形成共同的团结。来自不同非洲文化背景的被奴役者之间的持续互动产生了一种共同的身份认同,这种认同虽然各不相同,但却被对自由的渴望凝聚在一起。工人高度集中的种植园成了抗议的温床。谣言、歌曲、伏都教仪式和其他形式的交流迅速流传,使奴隶们能够秘密地组织起来。这些经常性的交流在很大程度上推动了反抗文化的发展,使协调大规模的抗议和反抗运动成为可能。法国大革命以自由、平等和博爱为理想,在激励奴隶方面也发挥了重要作用。法国动乱的消息传到圣多明各海岸,带来了人权观念,这些观念很快被采纳并适应了被奴役人口的需要。1791 年海地革命爆发时,这些奴隶人口稠密的地区最先陷入火海。叛乱很快演变成一场全面战争,奴隶、有色人种的自由人,甚至一些白人,都在与殖民军和试图维护既定秩序的欧洲君主国作战。1804 年的最终胜利见证了奴隶制的废除和一个新国家--海地的诞生,它证明了集体组织的力量、人民决心打破枷锁的决心和不屈不挠的精神。北部平原等地区的人口密度不仅为起义提供了便利,也让这股革命火焰得以绽放,燃烧得更加猛烈。 | |||

18 世纪,加勒比海地区的局势必然错综复杂,每个殖民地都有自己的特点。尽管大多数殖民地都是围绕种植园经济和奴隶制度建立起来的,但各殖民地之间还是存在着显著的差异。圣多明各是最富裕、人口最多的殖民地,奴隶密度特别高,这有利于他们之间的沟通和协调,使大规模起义成为可能。与此同时,法国大革命的冲击波横扫大西洋,特别是圣多明各。自由、平等和博爱的革命理想不仅得到了奴隶的广泛拥护,也得到了自由有色人种的拥护,从而激发了人们对自由的渴望。尽管牙买加和巴巴多斯等岛屿与圣多明各有许多相似之处,但它们也有自己的特点。例如,尽管牙买加曾发生过多次奴隶起义,但殖民者的反应往往是残酷的,使这些运动无法达到圣多明各的规模。这些殖民地的经济结构也发挥了作用。圣多明各的经济主要以甘蔗为中心,需要大量劳动力。这种依赖性加上残酷的工作条件,造成了比其他经济更多样化的殖民地更有利于叛乱的氛围。此外,其他地区的殖民国家在目睹了圣多明各发生的戏剧性事件后,也加强了安全措施,希望将类似的运动扼杀在萌芽状态。然而,尽管存在分歧,殖民国家也做出了努力,但叛乱精神一旦被点燃,就很难熄灭。随着时间的推移,废除奴隶制和争取平等权利的运动日益壮大,深刻影响了整个加勒比地区的发展轨迹。 | |||

在加勒比的中心地带,圣多明各奴隶文化的异质性矛盾地促成了他们之间更大的凝聚力。他们来自非洲各地,带来了各种语言、信仰和传统。这些差异非但没有阻碍他们团结起来,反而成为沟通的桥梁,促进了统一的克里奥尔文化的形成。更重要的是,这些传统的融合催生了新的表现形式和反抗方式,比如伏都教,它已成为许多人的文化和精神支柱。相比之下,牙买加和巴巴多斯的奴隶人口虽然具有多样性,但却更加单一。从理论上讲,这种同质性可能有助于统一,但也可能限制了思想和战略的相互交流,而这正是圣多明各抵抗运动的特点。同质化的人口有时在战术上会缺乏创新,依赖于既有的传统和做法。还应注意的是,每个殖民地都有自己的政治、经济和社会背景。圣多明各不同阶级之间的紧张关系,包括 "grands blancs"(富有的种植园主)和 "petits blancs"(贫穷的白人)之间的纠纷,以及白人和有色人种自由人之间的纠纷,都造成了裂痕,奴隶们可以利用这些裂痕来推动自己的事业。牙买加和巴巴多斯的具体动态尽管有某些相似之处,但与圣多明各的动态截然不同,从而影响了这两个殖民地各自的反抗轨迹。 | |||

圣多明各是法属西印度群岛皇冠上的明珠,其盈利能力远远超过其他殖民地,成为法国经济上的一大挑战。圣多明各的农业生产,尤其是蔗糖和咖啡,为王国的国库提供了充足的资金,因此控制其奴隶人口对于维持这笔意外之财至关重要。相比之下,虽然牙买加和巴巴多斯是英国的重要殖民地,但它们的生产和盈利水平都没有达到圣多明各的水平。它们的奴隶密度较低,加上农业生产利润较少,因此英国王室对它们的管理并不那么迫切。更重要的是,英国拥有庞大的殖民帝国,因此可以使收入来源多样化。这种轻重缓急的不同直接影响到每个殖民国家管理其领土的方式。在圣多明各,最大限度提高产量的巨大压力可能加剧了对奴隶的残暴行为,造成了有利于叛乱的更加紧张的气氛。在牙买加和巴巴多斯,虽然条件远非理想,但不那么紧迫的经济需要可能会稍微缓和虐待行为,尽管奴隶制与其他地方一样,本质上是残酷的。 | |||

圣多明各的社会结构是一个复杂的网状结构,远比牙买加和巴巴多斯等英国殖民地的社会结构更加微妙。在圣多明各的社会版图中,有色人种--通常是白人和黑人混血关系的后代--处于矛盾的地位。虽然他们享有一定程度的自由,但他们的权利仍然受到限制,因为他们被挤压在占统治地位的白人和被奴役的奴隶之间。他们的存在和相对成功是紧张局势的根源,因为他们藐视白人精英制定的种族规范,有时还拥有奴隶并参与商业事务。这个在经济上有影响力但在社会上被边缘化的中产阶级的存在无疑加剧了圣多明各本已存在的紧张局势。他们对社会平等的渴望以及对白人精英施加的限制的不满,促成了革命前的政治和社会动荡。相比之下,英国殖民地虽然也有有色人种的自由居民,但没有像圣多明各那样的成熟阶层或有影响力的阶层,因此由这一特殊动态引发的社会紧张局势较少。正是在这种情况下,圣多明各的有色人种自由人虽然与白人疏远,但也能够成为奴隶与白人精英之间的桥梁,在动员和策划革命方面发挥了关键作用,这场革命震撼了殖民地,并最终导致海地成为世界上第一个独立的黑人共和国。 | |||

法国大革命的动荡在圣多明各引起了强烈反响,凸显了自由、平等和博爱的理想,而这些理想与奴隶制是公然对立的。殖民地所有社会阶层,包括奴隶、有色人种自由人和白人精英,都听到了这些革命原则的回声。1789 年颁布的人权和公民权利的消息传到圣多明各有色人种自由人的耳中时,燃起了他们与白人完全平等的希望。有色人种自由人争取这些权利的尝试最初遭到白人精英的强烈抵制,但压力越来越大,白人之间出现分歧,一些人支持平等,另一些人则强烈反对,最终导致了让步。与此同时,法国的革命动荡引发了关于奴隶制未来的激烈辩论。黑夜之友协会等废奴团体主张结束奴隶制。这些辩论间接鼓励圣多明各的奴隶们考虑自己的解放问题。1794 年,当法国大革命公约废除奴隶制的消息传到圣多明各时,人们既抱有希望,又持怀疑态度。虽然这一消息鼓舞了被奴役的人民,但这一决定的实际执行却受到政治和军事障碍的阻碍,包括殖民势力的反对和外国干涉。法国不断变化的政治气候与圣多明各独特的地方动态相结合,为革命创造了肥沃的环境。法国大革命的理想不仅激励海地人为自己的自由而战,还提供了一个政治和意识形态框架,最终导致海地成为一个独立国家。 | |||

= | = 革命的起因 = | ||

The Haitian Revolution is a monumental example of the ability of an oppressed people to overthrow the powers that be and establish a new nation based on the principles of equality and freedom. The context of this revolution is rich and complex, shaped by the global and local dynamics of the eighteenth century. The mid-18th century was marked by an intensification of the transatlantic slave trade. Saint-Domingue, the pearl of the West Indies, became the beating heart of this slave-based economy, with a constant demand for African slaves to support its unprecedented production of sugar, coffee and indigo. These African slaves brought with them a diversity of languages, cultures and traditions, creating a complex, multicultural colonial society. However, beneath this façade of economic prosperity, tension simmered. The overwhelming majority of enslaved Africans were subjected to inhumane living conditions, working long hours under the scorching sun and often suffering brutal corporal punishment. What's more, the caste system based on skin colour created deep divisions, with a dominant white elite, a middle class of free coloureds and an enslaved majority. It was against this backdrop that the ideals of the Enlightenment began to permeate the colony. European philosophers preached liberty, equality and fraternity, and these concepts soon found an echo among those deprived of their fundamental rights. When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, advocating these ideals, it served as a catalyst for protest in Saint-Domingue. Toussaint L'Ouverture, despite starting life as a slave, embodied these Enlightenment principles. Thanks to his enlightened leadership, he was able to unite various rebel groups and lead a revolution against French colonial oppression. His ability to negotiate with foreign powers, to fight effectively against French, British and Spanish troops, and to introduce reforms laid the foundations for Haiti's independence. In 1804, after years of bitter struggle, Haiti became the first black republic in the world and the first nation to definitively abolish slavery. This triumph was not only a victory for the Haitians, but sent a powerful message to colonies around the world about the power of human resilience and the unshakeable desire for freedom. | The Haitian Revolution is a monumental example of the ability of an oppressed people to overthrow the powers that be and establish a new nation based on the principles of equality and freedom. The context of this revolution is rich and complex, shaped by the global and local dynamics of the eighteenth century. The mid-18th century was marked by an intensification of the transatlantic slave trade. Saint-Domingue, the pearl of the West Indies, became the beating heart of this slave-based economy, with a constant demand for African slaves to support its unprecedented production of sugar, coffee and indigo. These African slaves brought with them a diversity of languages, cultures and traditions, creating a complex, multicultural colonial society. However, beneath this façade of economic prosperity, tension simmered. The overwhelming majority of enslaved Africans were subjected to inhumane living conditions, working long hours under the scorching sun and often suffering brutal corporal punishment. What's more, the caste system based on skin colour created deep divisions, with a dominant white elite, a middle class of free coloureds and an enslaved majority. It was against this backdrop that the ideals of the Enlightenment began to permeate the colony. European philosophers preached liberty, equality and fraternity, and these concepts soon found an echo among those deprived of their fundamental rights. When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, advocating these ideals, it served as a catalyst for protest in Saint-Domingue. Toussaint L'Ouverture, despite starting life as a slave, embodied these Enlightenment principles. Thanks to his enlightened leadership, he was able to unite various rebel groups and lead a revolution against French colonial oppression. His ability to negotiate with foreign powers, to fight effectively against French, British and Spanish troops, and to introduce reforms laid the foundations for Haiti's independence. In 1804, after years of bitter struggle, Haiti became the first black republic in the world and the first nation to definitively abolish slavery. This triumph was not only a victory for the Haitians, but sent a powerful message to colonies around the world about the power of human resilience and the unshakeable desire for freedom. | ||

Version du 14 août 2023 à 09:29

根据 Aline Helg 的演讲改编[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

美洲独立前夕 ● 美国的独立 ● 美国宪法和 19 世纪早期社会 ● 海地革命及其对美洲的影响 ● 拉丁美洲国家的独立 ● 1850年前后的拉丁美洲:社会、经济、政策 ● 1850年前后的美国南北部:移民与奴隶制 ● 美国内战和重建:1861-1877 年 ● 美国(重建):1877 - 1900年 ● 拉丁美洲的秩序与进步:1875 - 1910年 ● 墨西哥革命:1910 - 1940年 ● 20世纪20年代的美国社会 ● 大萧条与新政:1929 - 1940年 ● 从大棒政策到睦邻政策 ● 政变与拉丁美洲的民粹主义 ● 美国与第二次世界大战 ● 第二次世界大战期间的拉丁美洲 ● 美国战后社会:冷战与富裕社会 ● 拉丁美洲冷战与古巴革命 ● 美国的民权运动

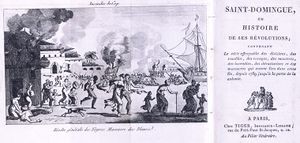

海地革命往往被历史章节所忽略,但它却是世界历史上最激进、最成功的革命之一。本课程旨在阐明这场具有重大意义的起义运动,不仅因为它能够彻底推翻既有秩序,还因为它对拿破仑时期法国在美洲的命运、拉丁美洲和加勒比地区的独立运动以及跨大西洋奴隶贸易和奴隶制本身的终结产生了重大影响。

对海地革命的研究揭示出,重大的历史动荡既可能源于结构性原因--如人口的突然增长,也可能源于外部影响--如对法国大革命平等和自由理想的吸收。正如拿破仑和图森-卢维杜尔等人物的发展轨迹所证明的那样,这些事件重新定义了权力的动态,即使是最有权势的人也会发现自己被革命运动的力量所压倒。事实上,海地今天在世界舞台上的地位在很大程度上是其在 1804 年宣布独立后遭到世界列强排斥和孤立的结果。

从 1804 年开始,这场革命体现了美洲每个奴隶主最阴暗的恐惧。它所灌输的恐怖将在今后许多年里影响奴隶主国家的政策。它不仅仅是一次简单的起义,它象征着从加勒比地区最有利可图的奴隶主殖民地之一过渡到一个为自己的独立而自豪的黑人主权共和国。

1789 年的圣多明各社会

1789 年,圣多明各不仅是法国的殖民地,还因其非凡的盈利能力而成为法国殖民皇冠上的明珠。圣多明各所在的伊斯帕尼奥拉岛被两个殖民国家瓜分。法国控制的西部三分之一是圣多明各,而东部的三分之二则是西班牙的殖民地圣多明各。

圣多明各的经济繁荣主要来自其广阔的种植园,这里种植着蔗糖、咖啡、棉花和蓝靛。这些商品在国际市场上备受青睐,使该殖民地成为整个殖民时期最赚钱的地方。然而,这些财富是以高昂的人力成本为代价的。种植园对劳动力的无限需求导致大量非洲奴隶涌入。事实上,被奴役的非洲人占人口的绝大多数,人数远远超过白人定居者和有色人种的自由人。

圣多明各的社会结构复杂而分层。在这个阶层的顶端,白人精英--通常被称为 "大白人"--拥有大部分土地并控制着大部分经济。接下来是 "小白人"、手工业者、店主和雇员。自由有色人种 "或 "黑白混血儿 "往往是白人定居者与奴隶或获得自由的非洲人之间关系的产物,他们处于中间地位,享有某些权利,但始终面临歧视。最后,处于最底层的是非洲裔奴隶,他们被剥夺了一切权利,任凭主人的胡作非为和残暴对待。

来自法国的自由和平等的革命理想加剧了这些群体之间的紧张关系,为革命铺平了道路。

人口

1789 年,作为法国殖民地的一颗明珠,圣多明各的人口状况既令人印象深刻,又因跨大西洋贩卖奴隶的现实而充满悲剧色彩。在 50 万左右的人口中,有不少于 88%,即 44 万人是被奴役的非洲人。这些数字本身就说明了圣多明各经济对强迫劳动的巨大依赖。这些奴隶中的大多数并不是在岛上出生的。相反,他们是作为跨大西洋贩卖奴隶行为的受害者,被迫离开非洲家园的。在非人的条件下,他们被挤在船舱里,许多人没能在渡海过程中幸存下来。那些幸存下来的人在圣多明各的奴隶市场上被当作动产出售,被迫在条件往往十分恶劣的糖、咖啡和其他经济作物种植园工作。这种人口结构造成了严重的社会后果。绝大多数被奴役人口拥有不同的传统、文化和宗教,对海地文化和社会产生了不可磨灭的影响。与此同时,奴隶与少数自由白人定居者和有色人种在数量上的反差造成了持续的紧张气氛,对奴隶起义的恐惧更是火上浇油。面对这一现实,该岛成为一个火药桶,等待着火花的爆发。自法国大革命以来横跨大西洋的自由和平等思想最终带来了这一火花,引发了海地革命,并最终建立了世界上第一个黑人共和国。

克里奥尔奴隶与非洲新来奴隶之间的区别是圣多明各奴隶社会的一个关键因素。每个群体都有自己的经历、文化和观点,这影响了他们在这个复杂社会中的地位。克里奥尔人是在殖民地出生的奴隶。他们在圣多明各出生和长大,往往更适应当地的气候和农业条件,对殖民社会的结构和期望也有一定的了解。更重要的是,这些克里奥尔奴隶往往从小就接触到法国主人的语言、宗教和风俗习惯,这往往使他们会说两种语言,或者至少能够与白人进行有效的沟通。相比之下,从非洲新来的奴隶(有时被称为 "bossales")则面临着完全的文化冲击。他们往往在横渡大西洋时受到创伤,带着自己的语言、信仰和传统来到这里。许多人从未接触过欧洲文化或加勒比种植园的大规模农业。因此,奴隶主普遍认为克里奥尔奴隶 "更可靠 "或 "不太可能 "造反。这是因为他们熟悉种植园的日常事务,而且接触欧洲统治的时间较长。另一方面,驼背奴隶则常常受到怀疑,因为他们缺乏同化和对非洲传统的依恋,被认为有可能反抗或叛乱。然而,必须指出的是,这些不同奴隶群体之间的团结在海地革命中发挥了至关重要的作用。虽然他们的经历和出身可能各不相同,但他们对自由的共同渴望和对奴隶制的反对将这些群体团结在一起,为争取解放而斗争。

圣多明各奴隶的人口构成和作用问题是复杂和多方面的。在法国殖民地圣多明各,使用非洲奴隶是其高利润经济的基石。1789 年,非洲奴隶占总人口的 58%,这表明该殖民地对跨大西洋奴隶贸易的严重依赖。但必须指出的是,奴隶的性别分布在不同时期和不同地区有所不同。女奴的经济价值以一种特殊的方式得到了认可。她们不仅被迫在甘蔗地、咖啡地、棉花地和蓝靛地从事繁重的劳动,而且还被视为奴隶劳动力 "繁衍 "的必要条件。奴隶子女的出生增加了奴隶主的资产,而无需从非洲进口昂贵的奴隶。对女奴的剥削不仅限于农业劳动。她们的身体经常受到奴隶主和监工欲望的支配,她们经常受到性虐待。女奴在漫长的工作之余还要承担照顾家庭的重任,确保非洲传统和文化在恶劣的环境中得以生存和传承。通过生育来繁衍后代和增加奴隶劳动力的压力反映了奴隶社会的不人道,在那里,个人被贬低到其经济价值,繁衍后代不是个人的选择,而是为殖民地经济利益服务的义务。随后发生的海地革命,部分原因就是这些深刻的不平等和对男女奴隶的系统性压迫。他们争取自由的斗争最终导致圣多明各废除奴隶制,海地共和国诞生。

法国殖民地圣多明各繁荣经济的核心是大片的甘蔗、咖啡和蓝靛种植园,而奴隶们无休止的劳动为这些种植园提供了动力。甘蔗种植需要在无情的烈日下长时间劳作,尤其辛苦。收获后,几乎没有时间将甘蔗运到磨坊,在那里榨汁生产糖和朗姆酒。咖啡种植虽然没有甘蔗种植那么紧张,但要求也不低。每一粒咖啡豆都要手工采摘,在变成欧洲人喜爱的饮料之前,需要对细节一丝不苟。靛蓝则为殖民地带来了鲜艳的色彩,使植物成为纺织业的珍贵染料。然而,奴隶制的影响远远超出了田野。圣多明各的港口城市,例如勒卡普和太子港,热闹非凡。在高雅的住宅中,家奴们照顾着从烹饪到家务的每一个细节,确保主人生活舒适。在街上,你可以看到奴隶工匠--木匠、铁匠和裁缝--他们的技艺代代相传,为殖民地的文化和经济财富添砖加瓦。港口尤其重要,因为它们是进出货物的过境点,奴隶们忙着装卸船只或修理船体。圣多明各的每个角落都浸透着奴隶们的汗水和辛劳。但是,无论他们的角色如何,他们都生活在殖民统治的枷锁之下,生活的特点是持续的监视、严格的纪律和无处不在的暴力。殖民地拥有耀眼的财富,却建立在对自由和人类尊严的无情压制之上。

在圣多明各的种植园里,艰苦的劳动和被迫的共处将来自不同非洲种族和文化的人们聚集在一起。在这种压迫环境下,各种传统和语言融合在一起,成为生存、交流和反抗的手段。海地克里奥尔语就是一个很好的例子:这种语言的诞生是为了超越多种非洲方言和强加的法语进行交流。它深深扎根于非洲语言,但也融入了殖民地主要语言法语的许多元素。除了语言上的融合,精神上的融合也在逐渐形成。奴隶们原有的宗教习俗遭到摧残,天主教强加给他们,为了应对这种情况,奴隶们创造了一种具有顽强生命力和适应性的精神信仰形式:伏都教。这种宗教融合了许多天主教圣人和符号,同时保留了万物有灵论信仰和非洲仪式的深度和丰富性。伏都教中的神灵或 "loas "通常与天主教圣徒相吻合,这是非洲祖先的信仰与基督教教义相融合的体现。这些语言和宗教方面的文化适应并不只是混杂,而是复原和身份认同的工具。在一个他们的人性不断被否定的世界里,这些传统为他们提供了一种声音、一种精神信仰和一个社区。克里奥尔语和伏都教成为抵抗、身份和人类精神不屈不挠能力的有力象征,即使在最恶劣的环境中也能找到表达自己的方式。

除了丰富的精神内涵,伏都教还成为圣多明各被奴役人口的身份认同和反抗的支柱。在残酷的奴隶制背景下,伏都教的习俗远不止是一种简单的崇拜:它是一种反抗行为,是一种坚持自己的非洲血统并谨慎地挑战既定秩序的方式。每晚的火把仪式、萦绕耳边的鼓声和祭祀舞蹈是奴隶们与祖先联系、寻求保护和力量的机会,也是他们面对不断试图否定其人性的制度而坚持自己人性的机会。历史上,伏都教在导致海地独立的叛乱中发挥了关键作用。1791 年的 Bois-Caïman 仪式通常被认为是海地革命的开端,当时奴隶们在精神领袖杜蒂-布克曼(Dutty Boukman)的带领下,通过伏都教仪式招魂,承诺为自由而战。今天,伏都教仍然深深扎根于海地的文化和精神结构之中。尽管伏都教有时在海地国内外受到鄙视和误解,但它象征着海地人民的坚韧、身份认同和文化延续性。对许多海地人来说,无论是在海地还是在海外,伏都教不仅是一种宗教,而且是一种活的遗产,是与祖先的联系,是取之不尽的精神力量源泉。

1789 年,尽管法国殖民地圣多明各为一些人带来了富裕和繁荣,但白人在总人口中只占极少数。事实上,他们仅占总人口的 7%,约 4 万人。这些白人中的大多数以男性为主,男女比例明显失衡。造成这种差异的原因有几个。首先,殖民地被许多欧洲人视为快速致富的地方,主要是通过耕种,然后带着积累的财富返回法国。由于热带疾病和社会政治紧张局势,这种冒险往往充满风险,更多的人是独自或把家人留在法国。此外,殖民地的生活条件、健康挑战和恶劣气候也让许多女性望而却步。然而,少数白人虽然在数量上处于劣势,却对殖民地的政治、经济和社会拥有相当大的影响力,他们精心策划并从残酷的奴隶制中获益,而奴隶制正是圣多明各经济的基石。

在法属殖民地圣多明各,白人人口虽然看似单一,但却按照社会经济和职业分层。处于这一阶层顶端的是大种植园主,通常被称为 "大白人"。这些人拥有巨大的种植园,主要种植甘蔗、咖啡和蓝靛。他们是大片农业庄园的首领,控制着大量奴隶。他们的财富往往相当可观,这使他们不仅在殖民地,而且在法国本土的权力圈中都具有重要的政治和经济影响力。然后是商人和贸易商。这些白人从事贸易,促进殖民地农产品出口到法国,并进口殖民地所需的商品。他们在圣多明各的经济中扮演着至关重要的角色,是殖民地与大都市市场之间的桥梁。王室官员是另一个重要类别。他们由法国国王任命,负责殖民地的行政管理,确保大都市的利益得到保护。他们是法国权力的直接代表,确保法律得到遵守,税收得到征收。最后,还有大量的士兵和水手。这些人确保殖民地的安全,保护法国的利益不受外部威胁,特别是海盗和敌对殖民国的威胁,同时也抵御内部叛乱,特别是奴隶起义。他们的存在对于维护秩序和法国王室对这片偏远殖民地的权威至关重要。尽管他们的职业和经济地位各不相同,但这些群体有着共同的利益:维护和保护奴隶制度,这是圣多明各繁荣背后的驱动力。

小白种人 "是圣多明各白人中一个独特的群体,但往往被忽视。虽然他们与殖民地的白人精英有着相同的肤色,但他们的经历和社会经济地位却大相径庭。他们大多来自法国,许多人来到圣多明各是希望抓住新机遇或攀登社会阶梯。然而,面对大地主和商人阶层的竞争,这些 "小白种人 "往往没有能力大规模投资土地或购买奴隶,他们只能充当工匠、小农或最富有阶层的雇员。他们通常生活在不稳定的环境中,是中下层阶级的代表。尽管他们相对贫穷,但他们决心保持自己的白人身份,以区别于自由混血儿,尤其是黑人奴隶。尽管他们没有经济手段或政治权力,但这种种族区别使他们具有某种社会优越感。矛盾的是,他们的处境十分脆弱。一方面,他们因明显的经济差距而憎恨白人精英,另一方面,他们又害怕奴隶或有色人种的解放运动会威胁到他们本已岌岌可危的地位。小白人"、大地主、有色人种和奴隶之间的紧张关系在圣多明各形成了复杂多变的局面,促成了最终导致海地革命的社会和政治动态。

在圣多明各殖民地,有色人种,尤其是黑白混血儿,构成了这个等级森严的社会中一个复杂多变的社会阶层。黑白混血儿通常由白人(通常是殖民者)和黑人妇女(通常是奴隶)结合而成,他们的父亲通常是白人,这使他们获得了与黑人奴隶不同的社会地位。由于他们的混血出身,他们发现自己跨越了两个世界。虽然他们并不享有与白人相同的特权,但他们中的许多人拥有土地和奴隶,并有机会接受教育,尤其是在法国。这种地位赋予了他们一定的经济影响力,但与此同时,他们也经常面临歧视和法律限制。例如,尽管一些黑白混血儿非常富有,但他们往往无法获得高级行政职务,并被排除在白人精英的某些社会领域之外。他们模棱两可的地位往往使他们处于殖民地社会矛盾的中心。一方面,他们渴望与白人更加平等,寻求废除基于肤色的歧视性法律。另一方面,作为奴隶主,他们享有比奴隶更高的社会地位,他们并不一定主张立即废除奴隶制。有色人种要求与白人享有平等权利,这在海地革命的开端发挥了核心作用。他们争取平等和承认的斗争,加上奴隶们渴望独立的愿望和白人之间的紧张关系,造成了一系列冲突和不断变化的联盟,最终导致了海地的独立。

在圣多明各殖民社会中,有色人种的自由状况充满了一系列矛盾。他们虽然获得了自由,而且往往拥有丰富的物质资源,但却受到一系列歧视性法律和习俗规定的阻碍。殖民社会制定了一套被称为 "黑人法典 "的法规,规定了奴隶和有色人种自由人的生活。这些规定建立了一个名副其实的种族等级制度,白人在上,自由有色人种在下,黑人奴隶在下。这些法律反映了当时的种族偏见,旨在维护既有秩序,防止混血儿和有色人种出现任何形式的社会上层流动。因此,自由有色人种的地位岌岌可危。尽管他们拥有自由身份,但其全面发展的能力却受到诸多限制。他们没有机会担任公职,往往被排除在精英职业之外,他们获取某些物品或完全融入白人社交圈的能力也受到阻碍。这种歧视往往被视为一种极度的不公正,导致这一群体的怨恨与日俱增。然而,尽管存在这些障碍,他们中的一些人还是设法积累了大量财富,特别是通过贸易和土地所有权。这加剧了他们与白人精英之间的裂痕,因为白人精英对他们的经济地位上升不屑一顾。最终,白人、有色人种自由人和黑人奴隶之间潜在的紧张关系导致了殖民地的日益不稳定和海地革命的爆发。这些对平等和正义的要求是革命运动背后的重要推动力,最终导致在 1804 年建立了世界上第一个自由黑人共和国。

圣多明各社会错综复杂,有色人种的自由人不容易被归入一个单一的类别。他们的经历和出身各不相同,甚至在这个群体内部也出现了分层。大多数有色人种是混血儿,由欧洲白人与非洲妇女或其后裔所生。然而,他们在社会阶层中的地位主要取决于他们的个人历史和家庭关系。有些人是女奴隶与白人主人结合所生,一出生就获得了自由,而有些人则是在被奴役多年后,成年后才获得自由。家庭纽带,尤其是白人父亲的认可,可以打开大门。这些后裔通常可以接受正规教育,有些甚至被送往法国学习,这给他们带来了社会经济优势。作为回报,他们通过建立贸易关系、获得土地和奴隶以及加入民兵等官方职位,加强了自己在圣多明各的影响力。然而,他们的肤色使他们处于白人精英的限制圈之外。尽管有些人能够获得可观的财富和影响力,但种族障碍往往使他们无法进入最高级别的社交圈。有色人种的自由妇女也占有特殊的地位。许多人与白人男子保持着非正式的结合关系。这些关系虽然是非正式的,但可以为妇女及其子女提供一些保护和经济利益。总之,在圣多明各,有色人种的自由地位是非常矛盾的。他们被夹在两个世界之间,社会和经济地位不断波动,既给他们带来机会,也给他们带来限制。这些动态因素导致了海地革命期间最终爆发的社会紧张局势。

18 世纪末,圣多明各曾是法国殖民地的一颗明珠,是甘蔗、咖啡和蓝靛种植园带来的巨大经济财富的中心。但这些财富是建立在残酷的奴隶制度和僵化的种族等级制度之上的,这种制度以复杂的方式将社会分层。处于等级制度顶端的是白人,特别是掌握经济和政治权力的大种植园主和商人。虽然他们只是少数人,约占人口的 7%,但他们对殖民地的控制是毋庸置疑的。他们拥有土地,控制贸易,并制定法律制度。自由有色人种(通常被称为 "有色人种 "或 "黑白混血儿")的地位十分微妙。他们的自由身份使他们有别于绝大多数被奴役的非洲人,赋予他们一定的法律和经济权利。然而,他们不断被占统治地位的白人社会边缘化,他们的非洲血统掩盖了他们的自由身份。对一些人来说,接受教育、获得财产甚至财富的机会都不足以让他们提升到与白人精英同等的地位。种族障碍根本无法逾越。但最悲惨的边缘群体或许是奴隶。他们从非洲进口到种植园工作,占人口的绝大多数,却没有任何权利。他们的生活受制于主人的意志和特别残酷的奴隶制度。这些群体之间的紧张关系造成了不信任和怨恨的气氛。白人精英时刻担心奴隶叛乱,有色人种的自由人渴望得到承认和完全平等,而奴隶则梦想获得自由。这些紧张关系最终导致了海地革命,这场起义动摇了殖民秩序的基础,并对整个大西洋世界产生了影响。

地区差异

1789 年,圣多明各殖民地的人口差距惊人,绝大多数居民生活在奴隶制的枷锁之下。88%的人口沦为奴隶,殖民地的经济基本上依赖于强迫劳动。广袤的农田反映了圣多明各的经济活力。甘蔗、咖啡、蓝靛和其他经济作物种植园推动了殖民地的经济发展。它们也是奴隶的主要雇主。这些规模庞大的劳动密集型农场需要大量工人来经营。大部分奴隶人口都集中在这些地区。这些从非洲输入的奴隶为种植园提供了劳动力,使殖民地成为西印度群岛的主要经济大国,并为法国本土创造了巨额利润。奴隶集中在经济作物区不仅是经济上的需要,也塑造了殖民地的社会地理。种植园本身就是一个社区,有自己的等级制度和社会动态,其核心是残酷的奴隶制。然而,奴隶高度集中在关键地区也给统治精英带来了风险。奴隶的接近和数量增加了叛乱和暴动的可能性,鉴于殖民地日益紧张的局势和明显的社会不平衡,这种担忧并非毫无根据。这些紧张局势最终爆发,引发了海地革命,这是美洲历史上最重要的革命之一。

圣多明各 "北部平原 "是殖民地经济机器跳动的心脏。这个肥沃的地区沐浴在有利的热带气候中,农业活动十分活跃,主要集中在甘蔗的种植上,甘蔗是殖民地的苦乐财富。甘蔗的利润无与伦比。甘蔗转化为蔗糖和朗姆酒带来了可观的附加值,这促使殖民者对这种作物进行大规模投资。然而,这种盈利能力是以巨大的人力成本为代价的。甘蔗的种植、收割和加工过程既繁重又劳累。这需要大量劳动力,因此该地区奴隶高度集中。北部平原的种植园规模宏大,组织严密。它们包括一眼望不到边的田地、压榨甘蔗的磨坊、蒸煮甘蔗汁和生产蔗糖的烤箱,以及酿造朗姆酒的蒸馏器。但在经济效益的表象背后,却是残酷的现实。这些种植园里的奴隶要在热带烈日下长时间从事艰苦的工作,几乎没有休息时间,而且随时可能受到严厉的惩罚。蔗糖种植的狂热节奏和要求也产生了社会影响。奴隶高度集中在北部平原导致了复杂的社会动态,不同的非洲文化在这里共存、融合,并创造了新的文化表达和抵抗形式。正是在这一地区,渴望自由和正义的奴隶们点燃了海地革命的第一束火花。

圣多明各东南部的土地虽然与北部平原一样肥沃,但主要种植甘蔗以外的作物。可可和蓝靛是这一地区的宝藏。用于生产巧克力的可可是一种珍贵的作物,在欧洲市场上非常抢手。可可豆经过收获、发酵、烘干和烘烤后,被加工成巧克力,这就是后来风靡全球的巧克力。可可种植园的工作条件虽然不如甘蔗园那么紧张,但仍然十分严格,奴隶们负责从种植到收获的所有工作。蓝靛则是一种染料植物。经过发酵和加工,靛蓝的叶子会产生一种受人追捧的蓝色,用来给织物染色。这种蓝色在欧洲备受推崇,圣多明各的蓝靛以其高品质而享有盛誉。与可可一样,靛蓝的生产也需要专门的劳动力,虽然生产过程与甘蔗不同,但仍然需要对奴隶进行劳动密集型的剥削。虽然人们经常强调北部平原在殖民地经济中的突出作用,但东南部地区及其可可和蓝靛作物也是重要的经济支柱。不同地区的社会互动就像作物本身一样各不相同,但不变的是殖民地对奴隶劳动的依赖,没有奴隶劳动,圣多明各的富裕是不可想象的。

到 18 世纪末,圣多明各的社会和经济结构清楚地反映了殖民制度的需要和要求。殖民地丰富的财富来自种植园,而种植园的位置在很大程度上影响着人口的分布。甘蔗是殖民地的主要经济作物,种植和加工都很密集。从种植到最后加工成糖和朗姆酒,都需要大量工人。因此,甘蔗种植园丰富的北部平原是奴隶最集中的地方。一望无际的甘蔗田每天都是劳作的场景,糖厂里到处都是将甘蔗加工成原糖和朗姆酒的奴隶。在东南部,虽然奴隶的数量相对较少,但他们对靛蓝和可可的种植至关重要。这一地区的种植园也需要专门的劳动力。奴隶们日出而作,日落而息,负责种植、收割、发酵和加工这些珍贵的作物。在农业区之外,奴隶集中在开普敦和太子港等城市地区,他们在那里充当佣人、工匠,或在码头和仓库工作。因此,圣多明各的人文地理与其经济地理密切相关。哪里对某种作物有需求,哪里就会有大量的奴隶来满足这种需求。这种结构遗留下来的悲哀是,尽管圣多明各是世界上最富有、最多产的殖民地之一,但这种繁荣是建立在被奴役、被剥夺权利和自由的人民的基础之上的。

圣多明各残酷的剥削制度为反抗和起义提供了肥沃的土壤。北部平原和东南部尽管表面上富庶,但背后却是社会的火药桶。对比十分鲜明。一方面,富裕的种植园主和商人生活相对奢侈,享受着强迫劳动的成果。另一方面,奴隶们却忍受着难以想象的痛苦,生活条件恶劣,如果辜负了主人的期望,就会受到残酷的惩罚。奴隶因简单的违法行为而受到严厉惩罚是司空见惯的事,基本权利的缺失更加剧了他们的绝望。家庭支离破碎,文化和传统遭到残酷压制,任何反抗或抗议的企图都会受到严厉惩罚。然而,在这种压迫的阴影下,开始出现了一些微妙的反抗形式。奴隶们利用宗教,特别是伏都教,不仅寻求精神慰藉,还将其作为团结社区的工具。伏都教仪式成为奴隶们远离主人视线、聚集和组织起来的场所。随着时间的推移,日益增长的不满情绪和集体意识催生了采取行动的愿望。有关法国大革命以及平等、自由和博爱理想的信息在奴隶中传播,给他们带来了希望和鼓舞。1791 年的海地革命将这些紧张局势推向了高潮。北部平原成为这场革命的中心,成千上万的奴隶在图森-奥维杜尔等标志性人物的领导下,拿起武器反抗压迫者。这场始于奴隶起义的革命很快演变成一场全面的革命,最终于 1793 年废除了奴隶制,海地最终于 1804 年获得独立。因此,这片曾经是奴隶制残暴象征的土地成为了世界上第一个自由黑人共和国的诞生地,也是历史上最成功的奴隶制革命的发源地。

奴隶集中在圣多明各最繁华的地区,如北部平原和东南部,这不仅仅是人口上的巧合,而是对起义的动力起了至关重要的作用。地理上的接近使奴隶们能够建立联系、交流信息,并在面对压迫时形成共同的团结。来自不同非洲文化背景的被奴役者之间的持续互动产生了一种共同的身份认同,这种认同虽然各不相同,但却被对自由的渴望凝聚在一起。工人高度集中的种植园成了抗议的温床。谣言、歌曲、伏都教仪式和其他形式的交流迅速流传,使奴隶们能够秘密地组织起来。这些经常性的交流在很大程度上推动了反抗文化的发展,使协调大规模的抗议和反抗运动成为可能。法国大革命以自由、平等和博爱为理想,在激励奴隶方面也发挥了重要作用。法国动乱的消息传到圣多明各海岸,带来了人权观念,这些观念很快被采纳并适应了被奴役人口的需要。1791 年海地革命爆发时,这些奴隶人口稠密的地区最先陷入火海。叛乱很快演变成一场全面战争,奴隶、有色人种的自由人,甚至一些白人,都在与殖民军和试图维护既定秩序的欧洲君主国作战。1804 年的最终胜利见证了奴隶制的废除和一个新国家--海地的诞生,它证明了集体组织的力量、人民决心打破枷锁的决心和不屈不挠的精神。北部平原等地区的人口密度不仅为起义提供了便利,也让这股革命火焰得以绽放,燃烧得更加猛烈。

18 世纪,加勒比海地区的局势必然错综复杂,每个殖民地都有自己的特点。尽管大多数殖民地都是围绕种植园经济和奴隶制度建立起来的,但各殖民地之间还是存在着显著的差异。圣多明各是最富裕、人口最多的殖民地,奴隶密度特别高,这有利于他们之间的沟通和协调,使大规模起义成为可能。与此同时,法国大革命的冲击波横扫大西洋,特别是圣多明各。自由、平等和博爱的革命理想不仅得到了奴隶的广泛拥护,也得到了自由有色人种的拥护,从而激发了人们对自由的渴望。尽管牙买加和巴巴多斯等岛屿与圣多明各有许多相似之处,但它们也有自己的特点。例如,尽管牙买加曾发生过多次奴隶起义,但殖民者的反应往往是残酷的,使这些运动无法达到圣多明各的规模。这些殖民地的经济结构也发挥了作用。圣多明各的经济主要以甘蔗为中心,需要大量劳动力。这种依赖性加上残酷的工作条件,造成了比其他经济更多样化的殖民地更有利于叛乱的氛围。此外,其他地区的殖民国家在目睹了圣多明各发生的戏剧性事件后,也加强了安全措施,希望将类似的运动扼杀在萌芽状态。然而,尽管存在分歧,殖民国家也做出了努力,但叛乱精神一旦被点燃,就很难熄灭。随着时间的推移,废除奴隶制和争取平等权利的运动日益壮大,深刻影响了整个加勒比地区的发展轨迹。

在加勒比的中心地带,圣多明各奴隶文化的异质性矛盾地促成了他们之间更大的凝聚力。他们来自非洲各地,带来了各种语言、信仰和传统。这些差异非但没有阻碍他们团结起来,反而成为沟通的桥梁,促进了统一的克里奥尔文化的形成。更重要的是,这些传统的融合催生了新的表现形式和反抗方式,比如伏都教,它已成为许多人的文化和精神支柱。相比之下,牙买加和巴巴多斯的奴隶人口虽然具有多样性,但却更加单一。从理论上讲,这种同质性可能有助于统一,但也可能限制了思想和战略的相互交流,而这正是圣多明各抵抗运动的特点。同质化的人口有时在战术上会缺乏创新,依赖于既有的传统和做法。还应注意的是,每个殖民地都有自己的政治、经济和社会背景。圣多明各不同阶级之间的紧张关系,包括 "grands blancs"(富有的种植园主)和 "petits blancs"(贫穷的白人)之间的纠纷,以及白人和有色人种自由人之间的纠纷,都造成了裂痕,奴隶们可以利用这些裂痕来推动自己的事业。牙买加和巴巴多斯的具体动态尽管有某些相似之处,但与圣多明各的动态截然不同,从而影响了这两个殖民地各自的反抗轨迹。

圣多明各是法属西印度群岛皇冠上的明珠,其盈利能力远远超过其他殖民地,成为法国经济上的一大挑战。圣多明各的农业生产,尤其是蔗糖和咖啡,为王国的国库提供了充足的资金,因此控制其奴隶人口对于维持这笔意外之财至关重要。相比之下,虽然牙买加和巴巴多斯是英国的重要殖民地,但它们的生产和盈利水平都没有达到圣多明各的水平。它们的奴隶密度较低,加上农业生产利润较少,因此英国王室对它们的管理并不那么迫切。更重要的是,英国拥有庞大的殖民帝国,因此可以使收入来源多样化。这种轻重缓急的不同直接影响到每个殖民国家管理其领土的方式。在圣多明各,最大限度提高产量的巨大压力可能加剧了对奴隶的残暴行为,造成了有利于叛乱的更加紧张的气氛。在牙买加和巴巴多斯,虽然条件远非理想,但不那么紧迫的经济需要可能会稍微缓和虐待行为,尽管奴隶制与其他地方一样,本质上是残酷的。

圣多明各的社会结构是一个复杂的网状结构,远比牙买加和巴巴多斯等英国殖民地的社会结构更加微妙。在圣多明各的社会版图中,有色人种--通常是白人和黑人混血关系的后代--处于矛盾的地位。虽然他们享有一定程度的自由,但他们的权利仍然受到限制,因为他们被挤压在占统治地位的白人和被奴役的奴隶之间。他们的存在和相对成功是紧张局势的根源,因为他们藐视白人精英制定的种族规范,有时还拥有奴隶并参与商业事务。这个在经济上有影响力但在社会上被边缘化的中产阶级的存在无疑加剧了圣多明各本已存在的紧张局势。他们对社会平等的渴望以及对白人精英施加的限制的不满,促成了革命前的政治和社会动荡。相比之下,英国殖民地虽然也有有色人种的自由居民,但没有像圣多明各那样的成熟阶层或有影响力的阶层,因此由这一特殊动态引发的社会紧张局势较少。正是在这种情况下,圣多明各的有色人种自由人虽然与白人疏远,但也能够成为奴隶与白人精英之间的桥梁,在动员和策划革命方面发挥了关键作用,这场革命震撼了殖民地,并最终导致海地成为世界上第一个独立的黑人共和国。

法国大革命的动荡在圣多明各引起了强烈反响,凸显了自由、平等和博爱的理想,而这些理想与奴隶制是公然对立的。殖民地所有社会阶层,包括奴隶、有色人种自由人和白人精英,都听到了这些革命原则的回声。1789 年颁布的人权和公民权利的消息传到圣多明各有色人种自由人的耳中时,燃起了他们与白人完全平等的希望。有色人种自由人争取这些权利的尝试最初遭到白人精英的强烈抵制,但压力越来越大,白人之间出现分歧,一些人支持平等,另一些人则强烈反对,最终导致了让步。与此同时,法国的革命动荡引发了关于奴隶制未来的激烈辩论。黑夜之友协会等废奴团体主张结束奴隶制。这些辩论间接鼓励圣多明各的奴隶们考虑自己的解放问题。1794 年,当法国大革命公约废除奴隶制的消息传到圣多明各时,人们既抱有希望,又持怀疑态度。虽然这一消息鼓舞了被奴役的人民,但这一决定的实际执行却受到政治和军事障碍的阻碍,包括殖民势力的反对和外国干涉。法国不断变化的政治气候与圣多明各独特的地方动态相结合,为革命创造了肥沃的环境。法国大革命的理想不仅激励海地人为自己的自由而战,还提供了一个政治和意识形态框架,最终导致海地成为一个独立国家。

革命的起因

The Haitian Revolution is a monumental example of the ability of an oppressed people to overthrow the powers that be and establish a new nation based on the principles of equality and freedom. The context of this revolution is rich and complex, shaped by the global and local dynamics of the eighteenth century. The mid-18th century was marked by an intensification of the transatlantic slave trade. Saint-Domingue, the pearl of the West Indies, became the beating heart of this slave-based economy, with a constant demand for African slaves to support its unprecedented production of sugar, coffee and indigo. These African slaves brought with them a diversity of languages, cultures and traditions, creating a complex, multicultural colonial society. However, beneath this façade of economic prosperity, tension simmered. The overwhelming majority of enslaved Africans were subjected to inhumane living conditions, working long hours under the scorching sun and often suffering brutal corporal punishment. What's more, the caste system based on skin colour created deep divisions, with a dominant white elite, a middle class of free coloureds and an enslaved majority. It was against this backdrop that the ideals of the Enlightenment began to permeate the colony. European philosophers preached liberty, equality and fraternity, and these concepts soon found an echo among those deprived of their fundamental rights. When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, advocating these ideals, it served as a catalyst for protest in Saint-Domingue. Toussaint L'Ouverture, despite starting life as a slave, embodied these Enlightenment principles. Thanks to his enlightened leadership, he was able to unite various rebel groups and lead a revolution against French colonial oppression. His ability to negotiate with foreign powers, to fight effectively against French, British and Spanish troops, and to introduce reforms laid the foundations for Haiti's independence. In 1804, after years of bitter struggle, Haiti became the first black republic in the world and the first nation to definitively abolish slavery. This triumph was not only a victory for the Haitians, but sent a powerful message to colonies around the world about the power of human resilience and the unshakeable desire for freedom.

The history of Haiti at the end of the 18th century is marked by an explosive dynamic in which economic, social and political forces collided, paving the way for a revolution unprecedented in the annals of the liberation of peoples. The core of this dynamic was the massive arrival of African slaves, who, despite their enslaved status, ended up playing a decisive role in the colony's destiny. Saint-Domingue, as Haiti was then known, became the epicentre of the French colonial economy in America, fuelled by the sweat and blood of these slaves. As plantations expanded and demand for labour increased, so did the number of imported African slaves. This policy had the effect of exacerbating the demographic imbalance. The slaves, who were predominantly young and African, quickly became the vast majority of the population, while the white settlers and the mestizo class, although enjoying a privileged position, were in the minority. This numerical disproportion, however, was far from the only source of tension. The brutality of working conditions, the flagrant disregard for human life and dignity, and the total absence of civil rights for slaves fuelled deep resentment. The oppression was not only physical, but also psychological. African traditions, languages and religions were systematically repressed, creating a deep sense of alienation. The irony, however, is that these same slaves, brought together from various parts of Africa, ended up creating a syncretic culture in Santo Domingo, mixing elements of their diverse origins with those of their European masters. This culture, with its new forms of solidarity and clandestine modes of communication, was to prove crucial in the preparation and conduct of the revolution. When the first sparks of rebellion flew, the white colonisers, despite their power and resources, found themselves faced with a rising tide of resistance, led by slaves determined to break their chains. The overpopulation of slaves in Saint-Domingue, although initially seen as a guarantee of economic wealth for the colony, became one of the key elements that led to its revolutionary upheaval. And in this melee, Haiti was born, carrying with it the hope and promise of a world where freedom is not a privilege, but an inalienable right.

The dynamics of race and class in Santo Domingo on the eve of the Haitian Revolution were deeply complicated. Free people of colour, or affranchis, formed an intermediate class between colonial whites and black slaves. Many were the product of relationships between white masters and their slaves, and as a result, some freedmen owned plantations and slaves themselves. Despite this relative prosperity, their position in colonial society was precarious due to racial prejudice. Freedmen were often educated, cultured and well-travelled. They were familiar with the philosophies of the Enlightenment, which advocated equality, liberty and fraternity. These ideas, radical in themselves, took on an even deeper meaning in the context of Santo Domingo, where people of colour were openly discriminated against and denied civil rights, despite their free status. Jean-Baptiste Belley is a perfect example of the complexity of this era. As Saint-Domingue's representative at the National Assembly in Paris, he embodied the fusion of the freedmen's worlds: both European in his culture and education, and Caribbean in his life experience. His role in the abolition of slavery in France was a decisive moment, not only for Haiti, but for all French colonial territories. The American War of Independence, with its rhetoric of freedom and rejection of oppression, also had a profound impact on the free people of colour who fought for France. For these soldiers, the idea of fighting for a nation's freedom, while being oppressed themselves, was a poignant contradiction. So while freedmen had economic interests that often aligned them with the white ruling class, their personal experiences of injustice, combined with their familiarity with Enlightenment ideals, made them sympathetic to the cause of slave emancipation. The convergence of these factors made this class an important, if not decisive, force in the Haitian revolution that was to follow.

The French Revolution, with its vast array of progressive ideas and its desire to redefine the social contract, had a domino effect on its colonies, particularly Saint-Domingue. The epicentre of these upheavals was in France, but their repercussions were felt thousands of miles away, in the rich Caribbean sugar colony. With the promulgation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789, France proclaimed that "men are born and remain free and equal in rights". Although this declaration was initially addressed only to French citizens, the universality of its message was clear. In a colony where the majority of the population was shackled by slavery, these words were both a promise of hope and a provocation. The weakening of French authority in Saint-Domingue, combined with the spread of the ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity, created a situation conducive to revolt. Slaves, freedmen and even some white settlers saw an opportunity to reshape society along the lines of the French revolutionary model. The power vacuum created by the unrest in France offered a unique opportunity to change the established order in Saint-Domingue. The spread of these revolutionary ideals was facilitated by free people of colour and freedmen who had links with France. Some had been educated in France, others had fought for France in various conflicts. These individuals played a crucial role in transmitting revolutionary ideals to the wider population of Saint-Domingue. So, as the French Revolution tackled inequality and absolutism at home, its ideas and institutional chaos provided the fuel needed to ignite the flame of revolt in its colonies. The Haitian Revolution, which followed, is a powerful testament not only to the will of a people to free themselves from their chains, but also to the global influence of the ideals of the French Revolution.

The French Revolution, which broke out in 1789, not only shook the foundations of Europe, it also sent shockwaves across the Atlantic, reaching the shores of its distant colonies, most notably Saint-Domingue, now known as Haiti. The impact of this revolution on Saint-Domingue was colossal, as it challenged the fundamental structures of power and society. The ideals emanating from France, such as liberty, equality and fraternity, resonated deeply with slaves and free people of colour in Saint-Domingue. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which asserted that all men are born free and equal in rights, was in stark contrast to the daily reality of the slaves. It was a contradiction that the oppressed in the colony were not prepared to ignore. The weakening of French control over the colony, due to the turbulence of the revolution, also opened a door. Slaves, freedmen and free people of colour saw a space to challenge the established order and claim the rights they had been denied for so long. This aspiration for freedom and equality, fuelled by the revolution in France, provided the impetus for the Haitian Revolution. Led by iconic figures such as Toussaint L'Ouverture, this revolution was marked by fierce battles, shifting alliances and unwavering determination. It culminated in the proclamation of Haiti's independence in 1804, making Haiti the first independent black republic in the world and the second independent country in the Americas after the United States. The impact of the French Revolution extended far beyond its borders, playing a decisive role in the end of slavery and the emergence of a new nation in the Caribbean. The Haitian Revolution is not only a testament to the power of the ideals of freedom and equality, but also proof of their universal relevance.

The colonies, and Saint-Domingue in particular, were the jewel in the crown of the French Empire. They were not only a major source of wealth through the export of raw materials, but also a symbol of national power and grandeur. When the winds of change of the French Revolution began to blow, Paris initially had no intention of significantly altering the status of these distant territories. After all, the sugar, coffee and cotton of Saint-Domingue filled the coffers of the French treasury, fuelling the economic engine of the metropole. However, the very principles that the French revolutionaries sought to establish in Europe - those of liberty, equality and fraternity - resonated with the slaves and free people of colour of Saint-Domingue. As the French revolutionaries fought for their rights in France, the oppressed of the colony saw an opportunity, a glimmer of hope for them too. Inspired by these ideals, they launched their own revolution, hoping that France would recognise their legitimate claims. But Paris, although overwhelmed by its own revolution, was reluctant to lose control of this lucrative source of revenue. What followed was an intense struggle, a delicate dance of diplomacy, betrayal and brutal battles. Despite desperate attempts by the French government to quell the revolt, the combined forces of the revolting slaves and their allies finally triumphed. In 1804, Haiti declared its independence, marking not only the birth of the first free nation in Latin America and the Caribbean, but also the first and only time in modern history that a slave revolt led to the formation of an independent nation. The impact of this victory on the French Revolution was profound. France, which preached freedom and equality, was confronted with a mirror reflecting its own contradictions. The brutal reality of slavery and colonisation clashed head-on with the revolutionary ideals, exposing the hypocrisies of the time. In this way, the Haitian Revolution not only redefined the future of a nation, but also called into question the very meaning of the principles that France claimed to defend.

The five stages of the revolution

1790 - 1791: Coloured freemen against whites

The Haitian Revolution, which began in 1790, was a major turning point in the history of the anti-colonial struggle. Although this uprising was initially initiated by the white elite of Saint-Domingue, who wanted to assert their authority over the colony in the light of the ideals of the French Revolution, it quickly took on a scope and dimension that were far different from what this elite had imagined. The white elite of Saint-Domingue, made up mainly of planters, merchants and lawyers, was deeply influenced by the world revolutions of the time. The ideas of the American Revolution, with its principles of autonomy, inalienable rights and democracy, resonated with these white settlers. However, they sought to take advantage of them to extend their own power, without necessarily considering liberating the enslaved black majority. For them, the revolution was a means of throwing off the shackles of the French metropolis and consolidating their hold on Saint-Domingue. What they did not foresee, however, was how quickly the ideals of freedom and equality would be embraced by enslaved Africans and people of colour. These groups, who had suffered centuries of oppression and slavery, seized upon revolutionary principles to claim their own freedom. The initial aspirations of the white elite were overwhelmed by a massive wave of resistance and demands from these oppressed groups. Emerging leaders like Toussaint L'Ouverture played a crucial role in channelling this revolutionary energy. Under their leadership, what had begun as a struggle for political power was transformed into a quest for total emancipation and independence. In 1804, after years of bitter struggle, Haiti became the world's first free black republic, delivering a powerful message about the strength and determination of oppressed peoples to determine their own destiny.

Free people of colour, often born of relationships between European settlers and African or Creole women, occupied a special position in the colonial society of Saint-Domingue. Despite their free status and, in many cases, their wealth and education, they were still discriminated against because of their mixed ancestry. They did not enjoy the same rights as white settlers, although they contributed significantly to the colony's culture, economy and society. The French Revolution, with its radical ideals of equality and liberty, offered people of colour a vision of a future in which they could be treated as equals. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted in 1789, affirmed that all men are born free and equal in rights. Although it was written with metropolitan France in mind, its principles resonated deeply with people of colour in Saint-Domingue. When tensions began to rise in the colony, these free people of colour saw an opportunity. Hoping to put an end to institutionalised discrimination and claim an equal place in society, they formed military units and took up the fight. Led by notable figures such as Vincent Ogé, they fought determinedly for their rights. The contribution of people of colour to the Haitian Revolution is essential to understanding the scale and complexity of the uprising. They acted as a bridge between the white elite and African slaves, navigating the complex waters of alliances and betrayals. Their role was essential in ensuring that the revolution was not just about a change of power, but a movement towards true equality and lasting independence.

The revolt led by Vincent Ogé was a key event in the rise of the Haitian Revolution. Although Ogé's rebellion was short-lived and ultimately failed, its importance lies in the message it sent and the tensions it exposed. When Vincent Ogé returned from France, where he had been exposed to revolutionary ideals, he tried to use peaceful means to advocate civil rights for coloured people. After being frustrated by the refusal of white elites to recognise these rights, he took up arms. The brutality of the repression of this rebellion by colonial forces shocked many people in the colony. Ogé and his allies were captured, tortured and executed in exemplary fashion. It was a shocking demonstration of the extent of racial divisions and hostility between coloured people and the white elite. Although Ogé's rebellion was put down, it nevertheless lit the fuse of resistance. The brutality of his end galvanised other people of colour and, more broadly, the enslaved population, strengthening their determination to fight against colonial domination. Ogé's revolt demonstrated the vulnerability of the colonial regime and signalled the beginning of a series of events that would intensify and culminate in the Haitian Revolution. The memory of Ogé and his struggle for equality has remained vivid, symbolising the sacrifice and aspiration for freedom of the Haitian people.

The reaction of the French metropolis to events in Saint-Domingue, and particularly to Ogé's rebellion, reflects the complexity and contradictions of the revolutionary period. The French Revolution proclaimed universal ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity, but its ability to apply these ideals to the colonies was limited, not least because of France's economic dependence on its colonies and the desire of colonial elites to maintain the status quo. The National Assembly's decision to grant civil rights to freedmen of colour born of free parents was a partial recognition of these ideals, but it was also very limited in scope. Moreover, it was widely interpreted by the colony's white elites as a direct intervention in their affairs and a challenge to their authority. On the other hand, for many freedmen, this measure was insufficient and they aspired to more extensive rights and, ultimately, the total abolition of slavery. The situation in Saint-Domingue before the Haitian Revolution was therefore a powder keg. Racial tensions, political rivalries and contradictions between revolutionary ideals and colonial realities created a climate of instability. The reaction of the metropolis to the rebellions in the colony, and its attempt to navigate between the contradictory demands of different social groups, only served to exacerbate these tensions. In the end, the Haitian Revolution became a powerful symbol of the struggles for freedom and equality, and demonstrated the limitations and contradictions of the French Revolution itself when it came to applying its ideals to the colonies.

1791 - 1793: Massive slave revolt, freemen of colour against whites and slaves

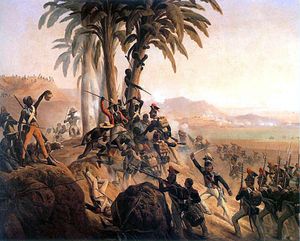

The Haitian Revolution, which took place against the tumultuous backdrop of the late 18th century, was profoundly influenced by the winds of change blowing in from Europe, particularly revolutionary France. In the rich French colony of Saint-Domingue, tensions were palpable long before the explosion of 1791. Society was stratified, with clear distinctions between the large white planters, the small whites, the freedmen (or people of colour) and the overwhelming majority of African slaves. It was a social powder keg ready to explode. On 21 August 1791, this explosion took the form of a massive slave revolt near Cap-Français, catalysed by a mystical voodoo ceremony at Bois-Caïman. This rebellion, which initially had no centralised leadership, spread rapidly, engulfing the colony in flames and chaos. The plantations, which were the economic heart of the island, were on fire, while the slaves used guerrilla tactics to confront their oppressors. In the midst of this tumult, several leaders emerged, but it was Toussaint l'Ouverture, a freed former slave with exceptional military skills, who emerged as the dominant figure. His rise to power coincided with a period when the colony became the focus of an international conflict involving not only local factions, but also the colonial powers of France, Great Britain and Spain. In 1793, to win the loyalty of the freedmen and counter the British, the French offered freedom to the slaves of Saint-Domingue. This promise was made official by the Convention in France the following year, extending emancipation to all the French colonies. These actions laid the foundations for what was to become the world's first independent black republic. The Haitian Revolution, though shaped by outside influences, ultimately became a powerful affirmation of humanity's ability to fight for freedom against all odds.

The slave insurrection in Santo Domingo is a remarkable chapter in the history of the struggle for freedom. In the wake of the French Revolution, news of the upheavals in Paris crossed the Atlantic, fuelling hope and a desire for equality among enslaved Africans. It was the 'elite slaves', often engaged in specialised work and possessing a degree of mobility, who played a pivotal role in transmitting this news and in the agitation that followed. These men, although still enslaved, had the relative privilege of interacting regularly with the ports, being in contact with sailors and merchants, and thus having access to crucial information. Tales of France, with its talk of equality, liberty and fraternity, ignited their desire to break the shackles of slavery. Armed mainly with machetes and the fervour of their cause, they launched a large-scale insurrection, burning the sugar cane fields that had symbolised their servitude and destroying the plantations that had been theatres of their oppression. Toussaint L'Ouverture, once a slave himself, quickly rose to power as a military strategist and charismatic leader. Under his leadership, what had begun as a series of scattered revolts turned into an organised revolution. He led his troops with a combination of tactical astuteness and fervent idealism, always seeking to establish the principles of equality and justice in Haiti. In the end, after years of fierce fighting, shifting alliances and betrayal, Haiti became the first colony to gain its independence through a slave revolt in 1804, and Toussaint, although he died before this victory, remains an emblematic figure of perseverance and triumph against oppression.

The rebellion quickly spread throughout the colony and tens of thousands of enslaved Africans took part. The enslaved Africans were able to destroy many plantations and kill or capture many white planters. In one month, more than a thousand plantations out of a total of 8,000 were burnt down and hundreds of whites were massacred. The rebellion gained momentum thanks to the leadership of figures such as Toussaint L'Ouverture, and the high level of organisation and coordination among the slave population. The rebellion also succeeded in defeating the French colonial forces and making Haiti an independent nation in 1804, becoming the first black nation in the world. The rebellion in Saint-Domingue, which began as isolated sparks of resistance, quickly turned into a consuming fire that engulfed the entire colony. In a remarkably short space of time, tens of thousands of African slaves rose up in a unified act of defiance against their colonial oppressors. With a speed and intensity that took the French authorities by surprise, the rebels devastated the plantations. In just one month, the economic landscape of the colony was radically transformed: more than a thousand of the 8,000 plantations were reduced to ashes. Hundreds of whites, living symbols of oppression, were killed in these assaults, sending a clear message about the determination and intensity of the rebellion. This impressive uprising cannot be attributed to the will to resist alone. It was reinforced by extraordinary leadership and meticulous organisation. At the heart of this revolution was Toussaint L'Ouverture. Once a slave, he rose to become a central figure in the insurrection, not only because of his strategic prowess, but also because of his ability to unite and galvanise the slaves towards a common goal. His leadership, combined with the unprecedented unity of the slave population, was a crucial factor in the successful challenge against the well-equipped colonial forces. Finally, after an intense struggle and years of confrontation, Haiti proclaimed its independence in 1804. The triumph of this small colony over a great colonial power was unprecedented. Haiti had not only become an independent republic; it was the first black nation in the world, a beacon of hope and opportunity for all those still living under the yoke of oppression.

The Haitian rebellion was a complex tapestry of motivations, aspirations and beliefs, interwoven in the tumult of the late 18th century. The French Revolution, with its declarations of human rights, certainly laid the foundations for protest in Saint-Domingue. However, not all the slaves who rebelled were necessarily imbued with the ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity promulgated by revolutionary France. Indeed, many enslaved Africans, particularly those freshly landed from African shores, were not fully informed or concerned by the political details of the European metropolis. Many of them believed, according to rumours spreading among them, that a benevolent king had already proclaimed their freedom, but that this decision had been concealed and withheld by the white planters and colonial administrators. In this spirit, their rebellion was not so much an act of revolution in the political sense, but rather a reclamation of a right that they believed had already been granted to them. This gave the revolt a unique nuance. It was not simply a struggle against the injustice of slavery per se, but also an insurrection against local authorities perceived as defying the will of a distant king. This perspective lent additional moral legitimacy to their cause, strengthening their resolve to fight not only the white masters, but also any colonial authority that perpetuated their servitude. It was in this complex context that figures like Toussaint L'Ouverture emerged, gradually fusing the different aspirations into a more cohesive movement for independence. Under such leaders, the Haitian rebellion grew in strength and organisation, finally culminating in victory in 1804 and the proclamation of Haiti as the world's first independent black nation, a resounding testament both to the strength of will of oppressed peoples and to the complexity of human motivations.

The outbreak of revolt in Saint-Domingue in the early 1790s was far from a simple confrontation between slaves and masters. It was a chaotic melee involving several factions, each with its own agendas, aspirations and grievances. The picture was complex: enslaved Africans thirsting for freedom, free people of colour seeking civil rights, and white planters determined to retain their power and social status. As the slave insurrection spread like wildfire across the plantations, the freemen of colour, who were often slave owners themselves, found themselves in a precarious position. Although discriminated against by the white elite, they were also feared and distrusted by the revolting slaves. Conflicts erupted, turning the colony into a chaotic battlefield where each group committed acts of unspeakable brutality against the others. French attempts to intervene and restore order only added fuel to the fire. The troops dispatched from France were ill-prepared for the tropical climate of the colony, and yellow fever claimed many of them before they could even engage in combat. In addition, the French forces also had to navigate the complex maze of shifting alliances and inter-group conflicts. The situation could have continued indefinitely without the charismatic leadership and strategic vision of figures such as Toussaint L'Ouverture. Although he initially fought for the Spanish, Toussaint eventually joined the French revolutionary forces when he became convinced that France, inspired by its own Revolution, was more likely to abolish slavery. Under his leadership, the rebel forces became more organised and disciplined, and eventually consolidated their control over the island. After years of fierce fighting, reversals of alliances and betrayals, the Haitian revolt triumphed. In 1804, Haiti became the first nation in the world to emerge from a successful slave rebellion, a beacon of freedom and determination in the Caribbean.

The arrival of Léger-Félicité Sonthonax in Saint-Domingue in 1792, mandated by the French National Assembly, marked a crucial stage in the complexity of the colonial conflict. Sonthonax, a fervent abolitionist, was the bearer of a decree granting equality to free men of colour, a revolutionary idea that ran counter to the age-old traditions of colonial society. Although this decision was eminently progressive and in line with the ideals of the French Revolution, it proved to be a source of additional tension in the colony, which was already in turmoil. The white planters, who had enjoyed unchallenged power and authority for centuries, saw Sonthonax and his policies as a direct threat to their hegemony. Their hostility towards him was palpable, and they saw his actions as a betrayal of French interests. Conversely, the free people of colour, who had long aspired to official recognition of their rights, saw him as an ally and supported his efforts to reform the colonial administration. But far from pacifying the situation, Sonthonax's actions exacerbated the divisions. The colony was already a powder keg because of earlier tensions between slaves, freemen of colour and whites. With civil war breaking out between the free coloureds and the white planters, the situation became even more precarious. It was against this backdrop that Toussaint L'Ouverture, initially an ally of Sonthonax, emerged as a powerful and unifying force. Despite his complex beginnings, initially fighting on behalf of the Spanish, he eventually embraced the French cause, particularly after Sonthonax abolished slavery in 1793. Over time, thanks to his charismatic leadership and military strategy, Toussaint consolidated his control over the island, even surpassing Sonthonax's authority. The road to Haiti's independence was not a linear one. The years that followed were marked by political intrigue, reversals of alliances and foreign intervention, particularly by Napoleonic France. However, in 1804, after years of bitter fighting, Haiti became the world's first black republic, a powerful symbol of resistance to oppression and the unshakeable will to be free.

In the last decade of the eighteenth century, Saint-Domingue was the scene of profound upheaval. As the rebellion led by Toussaint L'Ouverture grew in strength and influence, the resistance of the slaves against their colonial oppressors began to weaken, a sign of the rise of a new ruling class: the free people of colour. These freemen of colour, although oppressed by white supremacy, often had better education and resources than the majority of slaves. With the crumbling power of the white planters, these men and women of colour found themselves in a unique position to take the reins of power. Many whites, fearing for their lives and property in the face of this rise in power of former slaves and free people of colour, chose to go into exile, seeking refuge in Cuba, the United States, particularly Louisiana, or other parts of the Caribbean. Under the enlightened leadership of Toussaint L'Ouverture, a former slave who became a military and political leader, the free people of colour succeeded in forging a coalition with the slaves in revolt. This alliance, though fragile at times, became an unstoppable force that eventually dislodged the French colonial forces. In 1804, after a decade of fierce fighting, political intrigue and sacrifice, Haiti's declaration of independence was proclaimed. This victory was historic in many ways. Not only did Haiti become the first black republic in the world, it was also the result of a slave rebellion that succeeded in overthrowing its masters. The last vestiges of the old colonial order, the remaining whites, were eliminated or driven out, meaning that power was now firmly in the hands of the former slaves and the free people of colour. This period, while marked by triumphs, was also fraught with challenges. Establishing a fledgling nation from the ashes of a conflict-torn colony was no mean feat. Yet the legacy of the Haitian Revolution endures as a powerful testament to human resilience and the relentless quest for freedom.

In 1793, revolutionary France was in the throes of internal upheaval, but it also faced external challenges. The European monarchies of England and Spain, worried about the rise of radicalism in France, declared war on the young republic. The conflict quickly spread to the Caribbean, where these three great powers had major colonies. In Santo Domingo, the French colonial jewel in the Caribbean, the situation was particularly tense. With a slave revolt in full swing and an open war front with the British, France had to act quickly to hold on to this precious territory. It was against this backdrop that Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, the French commissioner stationed in Saint-Domingue, took a bold decision. Recognising that the support of the slaves would be crucial in repelling a British invasion, he proclaimed the abolition of slavery in August 1793. This move, although pragmatic, was extremely controversial. White planters, who derived their wealth from slavery, and even some freemen of colour who owned slaves themselves, saw the decision as a direct threat to their interests. However, by promising freedom to the slaves, Sonthonax created a formidable force of newly freed Africans, ready to defend the colony against any outside invasion. But it was Toussaint L'Ouverture, a former slave himself, who consolidated this decision. After repelling French colonial forces and taking control of Saint-Domingue, L'Ouverture ratified the abolition of slavery, laying the foundations for a new era for the colony. Not only did this secure the support of former slaves in defending the colony against foreign invasion, it also paved the way for Haiti's proclamation of independence in 1804, creating the world's first black republic.

1793-1798: Mobilisation of freed slaves and rise of Toussaint Louverture

In 1793, Saint-Domingue, the jewel in the crown of the French Caribbean colonies, was the scene of unprecedented unrest. The flame of the French Revolution had crossed the Atlantic Ocean, igniting the spirits of enslaved people yearning for freedom. Toussaint Louverture, himself a freed slave, emerged as one of the most charismatic figures of this revolt. Under his leadership, freed slaves began to push back the powerful white planters, overturning the established hierarchy and putting an end to centuries of white supremacy on the island. But the struggle for freedom in Saint-Domingue was not simply an internal revolt; it was part of a wider geopolitical context. The European powers, particularly England and Spain, saw the turmoil in the colony as an opportunity to extend their influence. These monarchies, concerned about the growing threat of the French Revolution, began to occupy parts of Saint-Domingue. Alliances were fluid and changing. While some freed slaves defended the French revolutionary ideal of equality and fraternity, others were attracted by tempting offers from the British and Spanish. The decision by Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, the French commissioner in Saint-Domingue, to abolish slavery in 1793 added another layer of complexity to this already complicated equation. Although the move was intended to win the support of the slaves against foreign forces, it sowed discord among the free people of colour, many of whom were slave owners themselves. They found themselves torn between their desire for equality and their economic interests. Against this tumultuous backdrop, Toussaint Louverture navigated skilfully, consolidating his power, uniting various factions and finally laying the foundations for an independent nation: Haiti, the first free black state in the world.

In the tumultuous context of late 18th-century Santo Domingo, the emergence of communities of maroons - former slaves who had fled the plantations - posed a major challenge to the established order. Determined never to return to the life of a slave, the maroons established bastions of resistance in the mountains and remote regions of the colony. These communities were not just refuges; they were the living symbol of a reconquered freedom, at a time when the abolition of slavery remained uncertain. Toussaint Louverture, with his strategic vision and talent for mobilisation, saw in these maroons an opportunity. By transforming these former slaves into a structured military force, he was able not only to defend the colony against colonial powers such as Great Britain and Spain, but also to promote the revolutionary message of freedom and equality. For his part, the French commissioner Sonthonax understood that allying himself with these maroons was crucial. Not only did they form a powerful military contingent, but their commitment to the ideal of freedom embodied the very principles of the French Revolution. So, rather than seeing them as a threat, Sonthonax saw them as essential allies in preserving French influence in Saint-Domingue. In the end, the alliance between Sonthonax, Louverture and the Maroons played a decisive role in defending the colony against foreign ambitions, and laid the foundations for the creation of Haiti, the first black republic in history.

1800-1802: The reign of Toussaint

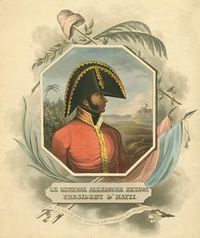

Toussaint Louverture, the emblematic figure of the Haitian Revolution, is a powerful symbol of the struggle for freedom and equality. Born a slave in Saint-Domingue, he transcended his condition to become a charismatic and skilful leader, guiding his people in a revolt against powerful colonial France. Thanks to his mixed background, blending African, Creole and French roots, Toussaint had a unique perspective that helped him navigate the cultural complexity of his native colony. His liberation from slavery at a relatively young age gave him the opportunity to educate himself. Unlike most slaves of his time, he was able to learn to read and write, which undoubtedly opened up new perspectives and strengthened his desire for equality for all. His education, combined with his natural shrewdness, enabled him to understand the political nuances of the time, which was marked by revolutions and social upheaval. Toussaint was not only a warrior; he was also a fine diplomat, manoeuvring skilfully among European powers, local factions and different social groups. He understood that to succeed, the revolution had to unite the different factions of Saint-Domingue under a common banner of freedom and independence. His vision, leadership and determination made him not only a champion of the Haitian cause, but also an inspirational figure for all those fighting oppression around the world. His life and legacy remain a powerful reminder of the power of the individual to change the course of history.

Toussaint Louverture's political and military trajectory during the Haitian Revolution is emblematic of the complex and rapidly changing political landscape of the time. His ability to navigate this shifting landscape, forming and breaking alliances according to what he felt was best for his people, is a testament to his political genius. After joining the French forces, Toussaint gradually increased his power and influence in Saint-Domingue. In 1798, he signed a treaty with the British, who had also tried to take control of the colony, forcing them to withdraw. With the Spanish already defeated, this left Toussaint as the dominant figure in the colony. Although formally allied with France, he operated with a large degree of autonomy. In 1801, he drafted a constitution for Saint-Domingue that granted the colony a great deal of autonomy, while recognising French sovereignty. He declared himself governor for life, further consolidating his power. However, Napoleon Bonaparte's rise to power in France marked a turning point. Napoleon sought to re-establish slavery and regain complete control of the colony. He sent a military expedition in 1802 to achieve these aims. Despite fierce resistance, Toussaint was captured in 1802 and sent to France, where he died in prison in 1803. Despite his capture, the spirit of resistance he embodied lives on. Under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, another leader of the revolution, Haitians continued to fight, culminating in Haiti's declaration of independence on 1 January 1804. Toussaint Louverture's legacy is vast. He was not only one of the main architects of the first and only successful slave revolution in history, but also an emblematic figure in the fight for human rights and freedom.

The alliance between Toussaint Louverture and André Rigaud was a crucial but complex chapter in the Haitian Revolution. Although the two leaders collaborated at one point, their differing visions for the future of the colony eventually led to an open conflict known as the War of the Knives (1799-1800). After jointly repelling the foreign forces, the differences between Toussaint, who primarily represented the island's black majority, and Rigaud, who represented the mulatto elite, became more apparent. These differences were rooted in issues of class, skin colour and vision for the future nation. Rigaud, anxious to preserve the power and privileges of the mulatto class, was less inclined to support total equality between blacks and mulattos. Louverture, for his part, aspired to a unified Haiti where distinctions based on skin colour would be minimised. The tension between the two camps came to a head in 1799, when the War of the Knives broke out between Toussaint's forces and those of Rigaud. This brutal civil war ended in Toussaint's victory in 1800, consolidating his control over most of the colony. Rigaud, after his defeat, went into exile in France before returning to Haiti after Louverture's capture in 1802. Despite their differences, it is essential to understand that both men's actions were guided by their desire to see a free and independent Haiti. However, their differing visions of how to achieve this goal created deep divisions, the impact of which was felt long after the revolution had ended.

Toussaint Louverture, emerging from the ferment of the late eighteenth century in Santo Domingo, carved his name as one of the most influential figures in Caribbean history. Born a slave, he took advantage of the turmoil of the French Revolution to rise as a brilliant military strategist, fighting first on the side of the Spanish against the French. However, the changing political winds at home, with the abolition of slavery in 1794, saw him ally himself with the French, strengthening their position in the colony by bringing them his army of 22,000 men. As he consolidated his power, Toussaint did more than just secure the abolition of slavery. He ambitiously reshaped the economic and political face of Saint-Domingue. His constitution of 1801, while affirming French sovereignty, nevertheless presented a Saint-Domingue where the freedom of former slaves was set in stone, and where he himself, Toussaint, was envisaged as governor for life. But this constitutional audacity was not without consequences. The metropolis, then under the aegis of Napoleon Bonaparte, saw these actions as a subversive step towards total independence. In an effort to tighten the grip on this lucrative colonial jewel, Napoleon launched a military expedition in 1802, with the hidden intention of restoring slavery. Toussaint, for all his military and political genius, was betrayed and captured, dying in captivity in France in 1803. However, his capture did not extinguish the flame of rebellion. Under the leadership of figures like Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the colony continued to resist, culminating in the historic proclamation of Haiti's independence on 1 January 1804. And so, through the ups and downs of the Haitian revolution, the figure of Toussaint has risen as an immutable symbol of the ideals of freedom and resistance against oppression.

Toussaint Louverture reached a new pinnacle of power in 1796 when the French government elevated him to the prestigious post of vice-governor of Saint-Domingue. This move not only recognised his military and political talents, it also cemented his place as a dominant force in the colony's tumultuous political landscape. With this new authority, Toussaint embarked on a methodical campaign to neutralise those who might challenge his ascendancy. One of his most notable opponents was Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, a fervent abolitionist and French representative. Although Sonthonax played a crucial role in the abolition of slavery in Saint-Domingue, ideological and strategic differences brought him into conflict with Toussaint. The astute expulsion of Sonthonax demonstrated not only Toussaint's political skill, but also his determination to have the last word on the fate of the colony. Despite the continued presence of French officials and troops, Toussaint established himself as the true de facto ruler of Saint-Domingue. While navigating his relations with France with caution, his main objective remained unchanged: to secure lasting freedom for the former slaves and lay the foundations for an autonomous and sovereign Haitian nation.

By the twilight of the eighteenth century, Toussaint Louverture, a determined strategist, had already extended his hold over large swathes of Saint-Domingue. By 1798, his troops had conquered the western and northern regions of the colony, marking rapid and decisive progress towards his goal of uniting the island under a single banner. But a major challenge remained: the east of the island, previously under Spanish control. Having succeeded in taking over this territory, Toussaint turned his attention to the south, still firmly under the grip of André Rigaud, the mulatto leader, and his allies. It was against this backdrop that the redoubtable Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a close ally of Toussaint, was sent to subjugate the south. This initiative triggered a ferocious war, often referred to as the "War of the Knives", between Toussaint's forces and those of Rigaud. The conflict, which was much more than a simple power struggle, took on a particularly dark tone due to the deep-seated animosities between Toussaint's black troops and Rigaud's mulattoes. The level of brutality and violence reached in this war was frightening, reminding us of the atrocity inherent in any conflict where the stakes are as much identity-based as political. Unimaginable acts of cruelty were perpetrated on both sides, fuelling mutual hatred and feelings of revenge. Behind this violent melee, however, Toussaint's main ambition remained clear: to unify the whole of Saint-Domingue and lay the foundations of an autonomous Haiti.

Toussaint Louverture's ascension to the leadership of Saint-Domingue was the result of a skilful interplay of strategy, determination and a clear vision for his country. At the conclusion of the war against André Rigaud's mulatto forces, he established himself as the colony's unshakeable leader, controlling every nook and cranny of the island. Toussaint's power and influence were unrivalled. Not only had he succeeded in freeing Saint-Domingue from the grip of slavery, but he had also laid the foundations of an autonomous Haiti, emancipated from the colonial yoke. The policies he put in place, although sometimes authoritarian, were primarily aimed at consolidating national unity, stimulating the economy devastated by the years of conflict, and building a solid, centralised state infrastructure. It cannot be denied that Toussaint's governance included elements of repression. He recognised the need for a firm hand to maintain order in a fledgling nation marked by deep divisions and a tumultuous history. However, alongside this rigid approach, there were also concrete efforts to propel the nation towards progress. He initiated agricultural reforms to boost production, encouraged trade and endeavoured to establish a solid administration. While skilfully navigating the tumultuous political and social landscape of his time, Toussaint Louverture left a lasting legacy. He laid the foundations for a free and autonomous nation, while laying the foundations for Haiti's future development.

1802-1804: Blacks and mulattos united for independence

The French invasion of Saint-Domingue in 1802 and the Haitian revolution

Napoleon Bonaparte's rise to power in France in 1802 marked a decisive turning point in the history of the colony of Saint-Domingue. The revolutionary ideals of freedom and equality, which had led to the abolition of slavery a few years earlier, were replaced by an imperialist desire to re-establish French control over the colony and reinstate slavery. Saint-Domingue, which had been one of the richest and most productive colonies in the world, represented an invaluable source of wealth and resources for Napoleon. His desire to re-establish slavery was motivated not only by economic considerations, but also by a desire to reassert French authority in the Caribbean and to thwart the ambitions of other European powers in the region. For Toussaint Louverture, who had devoted his life to fighting for Haiti's freedom and autonomy, Napoleon's arrival in power and his intentions for the colony were an existential threat. He had seen the transformation of Saint-Domingue from a land of servitude to a nation on the road to self-determination. He had also worked tirelessly to create a society in which former slaves were free and had rights. Toussaint's resistance to Napoleon's efforts was therefore motivated by a deep conviction that the ideals of liberty and equality had to be defended at all costs. This led to a direct confrontation with the French forces sent to restore order in the colony. The ensuing conflict became a powerful symbol of the struggle for freedom and self-determination, not only in Haiti but throughout the Caribbean region and beyond. Toussaint's opposition to Napoleon and his unwavering defence of the rights and dignity of his people made him a legendary figure and national hero in Haiti. He became a source of inspiration for other liberation movements around the world and continues to be an emblematic figure of resistance and freedom.

The threat posed by Napoleon's intentions in Haiti created a united front between blacks and mulattos, two groups that had previously been in conflict. The need to resist French efforts to re-establish slavery and re-impose colonial control transcended previous divisions and brought diverse forces together in a common cause. Toussaint Louverture played an essential role in this unification. His leadership, vision and unwavering dedication to the cause of freedom inspired and galvanised a broad coalition of resistance forces. He mobilised troops, built alliances and orchestrated a resistance campaign that stood up to one of the most powerful armies in the world. The ensuing conflict was brutal and costly. The French, under the command of General Charles Leclerc, employed ruthless tactics in an attempt to quell the rebellion. They burned villages, killed civilians and used torture in an attempt to break the Haitian resistance. However, the Haitian forces, although fewer in number and less well equipped, showed extraordinary courage and determination. They fought with a fervour that came from a deep conviction in their right to freedom and self-determination. In the end, despite Toussaint's arrest by the French and imprisonment in France, where he died in 1803, the Haitian resistance continued. The fierce struggle led by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a lieutenant of Toussaint, and other Haitian leaders led to Haiti's independence on 1 January 1804. The unification of blacks and mulattos, and their common struggle for independence, is a poignant testament to the power of the ideals of freedom and equality. It remains an important and inspiring chapter in world history and an enduring example of resistance and triumph against oppression.

Despite their differences, Toussaint Louverture and Napoleon Bonaparte shared common characteristics, including fierce ambition and a passion for power. Both believed in the promotion of certain egalitarian rights, even if their understanding and implementation of these rights sometimes differed profoundly. While Toussaint sought to protect the newly won freedom of his people and establish autonomy in the colony, Napoleon sought to re-establish slavery and French control over Haiti, seeing the colony as a valuable source of wealth and power. Their complex relationship culminated in military and political conflict. Toussaint's resistance to Napoleon's attempts to re-impose French control led to his capture. He was imprisoned in France, where he died in difficult circumstances in 1803. However, Toussaint's arrest did not put an end to the fight for Haitian independence. The Haitian resistance continued, inspired by Toussaint's legacy and guided by leaders such as Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Their struggle led to Haiti's independence in 1804, making it the first independent black republic in the world. The story of Toussaint and the Haitian Revolution is a powerful tale of resilience, determination and triumph in the face of adversity. It symbolises the universal struggle for freedom and equality and continues to inspire movements for rights and justice around the world.

Toussaint Louverture faced a complex dilemma when he sought to revive the economy of the colony of Saint-Domingue. The colony's wealth had traditionally been based on its plantation system, mainly in sugar and coffee production, which was based on slavery. After the abolition of slavery, the question of how to maintain the productivity of the plantations without reintroducing slavery was problematic. To solve this problem, Toussaint introduced a system of forced sharecropping. Former slaves were required to work on the plantations, but unlike slavery, they received a share of the harvest as payment. This system was intended to balance the need to revive the economy with the promise of freedom and equality for former slaves. However, the system was not without controversy. Some critics argued that forced sharecropping was too much like slavery, imposing strict constraints on where and how former slaves could work. Freedom of movement was limited, and workers were often tied to the plantations where they had previously been slaves. Toussaint defended this system, arguing that it was necessary to restore prosperity to the colony and ensure economic stability. He believed it would allow former slaves to share in the fruits of their labour and participate in the economy in a way they had previously been denied. The system of forced sharecropping under Toussaint demonstrated the tensions and difficult compromises involved in creating a post-slavery society. It also illustrates the complexity of Toussaint's leadership, which sought to navigate these delicate issues with a combination of pragmatism and idealism. The question of how to combine freedom, equality and economic prosperity remains a challenge in many societies, and Toussaint's experience offers valuable reflection on these universal themes.