Marxism and Structuralism

| Faculté | Faculté des sciences de la société |

|---|---|

| Département | Département de science politique et relations internationales |

| Professeur(s) | Rémi Baudoui |

| Cours | Introduction to Political Science |

Lectures

- From Durkheim to Bourdieu

- The origins of the fall of the Weimar Republic

- Max Weber and Vilfredo Pareto

- The notion of "concept" in social sciences

- Marxism and Structuralism

- Functionalism and Systemism

- Interactionism and Constructivism

- Interests

- The institutions

- Ideas

- The theories of political anthropology

- What is War?

- The War: Concepts and Evolutions

- The reason of State

- State, sovereignty, globalization and multi-level governance

- What is Violence?

- Welfare State and Biopower

- Political regimes and democratisation

- Electoral systems

- Governments and Parliaments

- Morphology of contestations

- Régimes politiques, démocratisation

- Action in Political Theory

- Introduction to Swiss politics

- Introduction to political behaviour

- Public Policy Analysis: Definition and cycle of public policy

- Public Policy Analysis: agenda setting and formulation

- Public Policy Analysis: Implementation and Evaluation

- Introduction to the sub-discipline of international relations

- Introduction to Political Theory

Marxism is a socio-economic theory and a method of socio-political analysis based on the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. It is primarily critical of capitalism and aims to replace it with communism, a classless society. Marxism states that all societies progress through class struggle, a confrontation between the ruling class and the oppressed classes. Structuralism, on the other hand, is a theoretical approach mainly used in the social sciences, humanities, psychology, anthropology and linguistics. It focuses on understanding the underlying structures that determine or shape human behaviour, perception and meaning. Structuralists argue that reality can only be understood by examining the larger systems that shape individuals and events. Structuralo-Marxism is a school of thought that attempts to merge the ideas of Marxism and structuralism. It seeks to understand how social and economic structures determine the behaviour and perception of individuals, while keeping in mind the class struggle and the role of capitalism in structuring these systems. Structural Marxists argue that capitalism is a structure in itself that shapes the behaviour and perception of individuals.

To structure our discussion, we will begin with an examination of Marxism, focusing on the contributions of its founder, Karl Marx. Then we turn to structuralism, exploring in depth the work of the famous anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. Finally, we conclude by assessing the lasting influence of Marxist thought on the political sphere.

Marxism

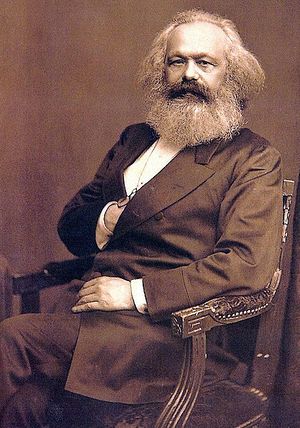

Karl Marx : 1818 - 1883

Marx is a key personality of the 19th century. He will cross it, confronting the exceptional mutation of this century marked by the industrial revolution which goes beyond all the social, political and cultural frameworks of the old regime. We're being thrown into an upheaval that Marx is going to want to echo.

Born into a family of Jewish lawyers converted to Protestantism, he grew up in an easy and favorable environment that was not revolutionary, but conducive to intellectual development. He will combine three subjects: the law which enables him to understand that it is a science of the structuring of societies by its normative dimension which imprints society by its mode of functioning and regulation; history which offers a field of long duration to interpret events and phenomena. Rapidly, it will be marked by the readings of the first socialists. He then completed his studies in philosophy at the major universities of the time, Bohn and Berlin.

In 1841, Marx defended a doctoral thesis on Epicure[1]. Between 1841 and 1845, he began to absorb the first revolutionary doctrines that appeared and were already based on a revolutionary socialism that took into consideration a very hard world for work combined with a rise in power of capitalism called the "first capitalism". It is a capitalism of exploitation without social consideration of labour.

He lives in an environment that will quickly make him aware of political protest. Thus, from 1840, he became pre-revolutionary, being driven back from Prussia and France. In Germany, he became editor of the Rhineland Gazette, which got him into trouble, and as an opposition newspaper with a democratic and revolutionary tendency, as editor-in-chief he participated in the German revolutionary effervescence.

The history of Marx is the constitution of the revolutionary international. The emergence of the capitalist society sees the emergence of a diaspora of intellectuals and thinkers scattered in the great capitals that organize themselves, allowing the development of revolutionary thought.

In Paris, he met Engels, who was campaigning and reflecting on a number of reforms to be introduced. Thus, Marx will develop a revolutionary proletarian socialist theory that legitimizes violence; violence is an element of combat; the question of social violence is legitimate. The only way to transform society is to propose revolution. He is brought to justice and goes to Belgium from where he will also be expelled.

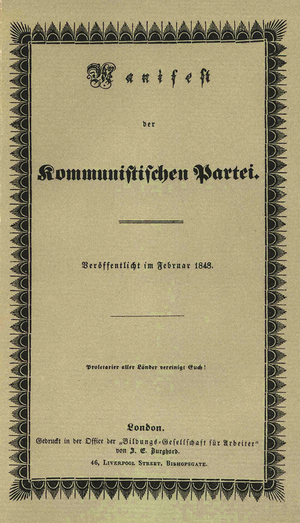

Starting from the Communist Party Manifesto in 1867, he began to question one of the major components of capitalism, as Weber had understood in his book on Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism, that in order to understand capitalism, one must integrate the question of capital.

For many years Marx wrote Le Capital until its publication in 1867. It revolves around a new specific vocabulary which is the concept of political economy. Economics is not outside politics, it conforms to and describes a political system. In other words, the economy is not outside society, but it is the basic premise that the economy is an integral part of society. Political economy links economic issues to the systems that regulate them.

Marx was delighted with the revolution of 1848 in France and the social conflicts that were born, all signs of the transformation of society through revolution.

From 1864 onwards, he was part of the International Socialist Workers' Party of which he was an eminent member. This movement will organize the pre-revolutionary socialist movements.

After Le Capital, he will ask himself about the commune. Finally, he will examine the relations between social classes and capital as well as the challenge of a collective struggle at the level of the European peoples.

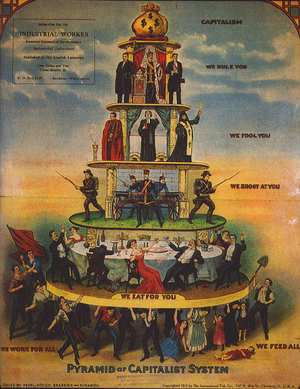

Classes and class struggles

Marx was a very versatile thinker. His work spanned many fields, including philosophy, sociology, economics and politics. His critique of capitalism, as set out in works such as "Capital", is still influential and relevant today. We must first start with an apriori from the Manifesto, saying that "the history of all society up to the present day has been the history of class struggles". This quote is from the "Manifesto of the Communist Party", co-authored by Marx and Friedrich Engels. It is one of Marx's most famous statements, which sums up his view of history as a series of class conflicts. According to him, all society is structured around the relations of production - the relations between those who own the means of production (the bourgeoisie) and those who sell their labour power (the proletariat). This dynamic creates an inherent conflict, a class struggle, which is the engine of social and historical change.

Marxism, as a theory, is therefore deeply concerned with questions of power, control and conflict in the economic context. For Marx, the economy is not a separate sphere from social and political life, but is intrinsically linked to it. Capitalism, as an economic system, shapes and is shaped by social and political structures. It is this understanding of the interconnectedness of economics, politics and society that makes Marx not only an economist or political philosopher, but also a revolutionary social theorist.

For Marx, a class is defined not only by its relation to the means of production, but also by its class consciousness - a shared understanding of its position in the capitalist system of production and its interests in opposition to those of other classes. This class consciousness is not automatic or natural, but is the product of lived experience and struggle. In "Capital", Marx talks about the process by which workers, who are initially in competition with each other in the labour market, begin to recognise that they share a common position and common interests in opposition to those of the bourgeoisie. It is this process of awareness and solidarity formation that allows for the formation of a class as a political force. However, Marx also pointed out that the bourgeoisie uses various strategies to prevent working class consciousness, such as dividing workers along racial, ethnic or gender lines, or spreading ideologies that justify and naturalise class inequality. This idea was later developed by Marxist theorists such as Antonio Gramsci, who spoke of the cultural hegemony of the bourgeoisie. Thus, for Marx, the class struggle is not only an economic struggle, but also an ideological and cultural struggle. It is a struggle for class consciousness, for the recognition of common interests and for collective organisation for social change.

Marx argued that in a capitalist society, different classes have fundamentally divergent economic interests that lead to antagonistic goals. For example, the bourgeoisie, which owns the means of production, seeks to maximise its profits. This can be achieved by reducing the costs of production, which often includes reducing wages or extending working hours for the working class. On the other hand, the proletariat, which sells its labour power, has a direct interest in raising wages and improving working conditions. These divergent interests are intrinsic to the capitalist system and lead to a constant struggle between the classes. These class antagonisms limit the possible actions of each class. For example, the working class is limited in its actions by the need to sell its labour power in order to survive, while the bourgeoisie is limited by the need to maximise profits to remain competitive in the capitalist market. Furthermore, these class antagonisms also shape the political field. According to Marx, the state under capitalism generally acts in the interests of the bourgeoisie and seeks to maintain the existing class order. This means that attempts by the working class to change the system are often met with resistance from the state and the ruling class. For Marx, class struggle is not only a characteristic of capitalism, but also a barrier to action, as it reflects divergent and antagonistic interests between different social classes.

For Marx, class struggle is the motor of history and social evolution. Society is not a harmonious collection of individuals with convergent interests, but rather is marked by fundamental conflicts and class antagonisms. Class struggle is not only an economic reality, but also a social and political reality. It shapes people's consciousness, their identity and their understanding of the world. By confronting exploitation and class oppression, individuals begin to develop a class consciousness - an understanding of their common position and common interests as a class. This class consciousness can lead to collective organisation and resistance, and ultimately to the transformation of society. However, class society does not simply disappear with the announcement of formal freedom or equal rights. On the contrary, class society persists and continues to structure social, economic and political life, even in modern societies that present themselves as free and equal. For Marx, class struggle is both the product of class society and the means by which that society can be transformed. It is a profoundly conflictual and dynamic worldview, which emphasises the role of struggle, resistance and change in human history.

"Modern bourgeois society (...) has not abolished class antagonisms. It has merely substituted new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle for those of the past. This quote comes from Marx and Engels' "Manifesto of the Communist Party", and it summarises an important part of their analysis. According to them, the bourgeois revolution - that is, the transition from feudalism to capitalism that took place in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries - did not abolish class antagonisms, but rather transformed their nature. In feudal society, the main classes were nobles and serfs. With the advent of capitalism, these classes were replaced by the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The bourgeoisie, as the class that owns the means of production, became the new dominant class, while the proletariat, which sells its labour power to the bourgeoisie, became the new oppressed class. However, even though the precise nature of class oppression and domination changed, Marx and Engels argued that the fundamental antagonism between classes remained. Capitalism, like feudalism, is based on the exploitation of the working class by the ruling class. Moreover, Marx and Engels argued that capitalism has in fact exacerbated class antagonisms. Capitalism is characterised by extreme class inequality and inherent instability, with recurrent economic crises exacerbating the class struggle. This is why they argued that capitalism would eventually be replaced by communism, a classless society where the means of production would be collectively controlled.

Capital and salaried labour

The movement of capital

For Marx, the bourgeoisie is defined by its relationship to the means of production - it owns and controls the factories, machines, land and other means of production that are needed to produce goods and services. The working class, on the other hand, does not own these means of production and therefore has to sell its labour power to the bourgeoisie in exchange for a wage. According to Marx, the main goal of the bourgeoisie is the accumulation of capital. This means that it constantly seeks to increase its wealth by maximising profits and minimising costs. One of the main ways to achieve this is to exploit the labour power of the working class. Workers are paid less than the full value of what they produce, and the difference (what Marx calls 'surplus value') is retained by the bourgeoisie in the form of profits. From this perspective, the bourgeoisie has no particular interest in the welfare of the working class, except insofar as it affects its ability to produce surplus-value. Consequently, there can be a constant tension between the bourgeoisie and the working class, as the former seeks to maximise its profits while the latter seeks to improve its wages and working conditions. It is this tension, this class struggle, which is at the heart of Marx's view of capitalism. For him, capitalism is a system of exploitation that creates inherent inequalities and class conflicts. And it is this class struggle that, according to him, would ultimately be the motor of social transformation and the transition to a classless society.

For Marx, capital is not simply a sum of money or a stock of goods. Instead, he defines it as "value in process" or "self-increasing value". In the capitalist system, capital is invested in the purchase of means of production (machinery, raw materials, etc.) and labour power. These elements are then used to produce goods or services which are sold on the market. The value of these goods or services is greater than the sum of the value of the means of production and labour power initially purchased. This difference is what Marx calls "surplus value", and it is the source of capitalist profit. In this process, there is a clear division between the owners of capital (the bourgeoisie) and those who sell their labour power (the proletariat). The bourgeoisie uses its capital to generate more value, while the proletariat is paid a value (in the form of wages) that is less than the value it produces. It is this extraction of surplus value from the working class that, according to Marx, constitutes the exploitation at the heart of capitalism. Thus, for Marx, the ultimate goal of capital and its owners is not simply the production of goods or services, but the accumulation of more value. This is what motivates the capitalist system and is also the source of its contradictions and crises.

The origin of the surplus value

For Marx, the objective of the capitalist is not simply to produce goods or services, but to generate surplus value. This surplus value is the difference between the total value of the goods or services produced and the value of the inputs used for their production, including labour power. In the capitalist system, this surplus value is constantly reinvested to generate even more value. This is what Marx calls capital accumulation. It is a never-ending process, where money is invested to generate more money. This dynamic of perpetual accumulation is at the heart of the capitalist system. It leads to constant economic growth, but also to increasing inequality, as surplus value is appropriated by the capitalists rather than by the workers who produce it. Moreover, this dynamic of perpetual accumulation can also lead to economic crises, as the constant search for surplus value can lead to overproduction and economic instability. For Marx, capital is not simply a sum of money or a stock of goods. It is a social relation based on exploitation, where surplus value is extracted from workers' labour and reinvested to produce even more value.

In the capitalist system, surplus value - that is, the value created by labour beyond what is necessary to sustain the worker - is appropriated by the capitalist rather than redistributed to the workers. The capitalist then reinvests this surplus value to generate even more capital, in a process Marx calls "capitalist accumulation". This accumulation of capital leads to an increasing concentration of wealth in the hands of a small elite of capitalists, while the majority of workers remain relatively poor. This creates ever greater inequality in society. Moreover, this accumulation of capital does not necessarily benefit society as a whole. For example, it can lead to overproduction of goods, economic crises, and increased exploitation of workers. For Marx, the capitalist system is inherently unequal and unstable. He argued that the only way to solve these problems would be to replace capitalism with communism, a system in which the means of production are controlled collectively by the workers themselves.

Work and overwork

It is possible to highlight two key concepts in Marxist economics: constant and variable capital, and the two forms of surplus value - absolute and relative surplus value.

Constant capital, as you mentioned, includes the non-human means of production such as machines, factories and raw materials. This capital does not create new value in itself, but transfers its own value to the finished products.

Variable capital, on the other hand, is the part of capital used to pay for labour. This capital is called 'variable' because it is capable of producing new value beyond its own value. That is, workers are able to produce more value than they receive in the form of wages.

Absolute surplus value is generated by extending the working day. If a worker can produce enough to cover his wage in five hours, but works ten hours, then the extra five hours of unpaid work generates absolute surplus value for the capitalist.

Relative surplus-value, on the other hand, is generated by reducing the labour time needed to produce a commodity, usually through technological innovation or improved efficiency. If a worker can produce a commodity in two hours rather than four, then the value of that commodity falls and the capitalist's relative surplus value rises.

Finally, Marx sees these processes as having limits. There is a limit to the length of the working day and to a worker's capacity to work. Similarly, there is a limit to the amount of relative surplus-value that can be generated through improved efficiency. These limits, according to Marx, are sources of tension and conflict in the capitalist system.

Accumulation

There are two major results of capital accumulation according to Marx: the concentration of capital and the creation of an overpopulation of workers.

- Concentration of capital: According to Marx, the process of capital accumulation inevitably leads to an increasing concentration of wealth and economic power. In other words, more and more capital ends up in the hands of fewer and fewer capitalists. This creates a fundamental contradiction in the capitalist system, because although capitalism is based on the idea of competition, its functioning tends to destroy this competition by favouring the formation of monopolies.

- The creation of an overpopulation of workers: Marx also argues that the process of capital accumulation leads to the creation of an "industrial reserve army" of unemployed workers. This is due to the constant improvement of technology and efficiency, which allows capitalists to produce more with fewer workers. This overpopulation of workers serves to keep wages down, as there is always a reserve of workers ready to take the place of those who demand higher wages.

Ultimately, Marx sees these tendencies as leading to an intensification of class conflict and, ultimately, to revolution. He argues that the proletariat, which is both oppressed by capitalism and vital to its functioning, has both the interest and the power to overthrow the capitalist system and replace it with communism.

The contradictions of capitalism

Marx soutient que le capitalisme contient des contradictions inhérentes qui, selon lui, mèneront finalement à sa propre déconstruction. Ces contradictions sont principalement le résultat de la dichotomie entre le capital et le travail dans une économie capitaliste. Voici comment il voit ces contradictions :

- Contradiction entre le capital et le travail : Le capitalisme repose sur la relation entre les capitalistes, qui possèdent les moyens de production, et les travailleurs, qui vendent leur force de travail en échange d'un salaire. Selon Marx, cette relation est fondamentalement conflictuelle car les intérêts des capitalistes et des travailleurs sont diamétralement opposés. Les capitalistes cherchent à maximiser les profits en minimisant les salaires et en maximisant le temps de travail, tandis que les travailleurs cherchent à maximiser leurs salaires et à minimiser leur temps de travail.

- Contradiction entre l'accumulation du capital et la surpopulation relative : Comme vous l'avez mentionné précédemment, l'accumulation du capital entraîne une concentration de la richesse et une surpopulation relative de travailleurs. Cela crée une tension car il y a une offre excessive de main-d'œuvre par rapport à la demande, ce qui peut entraîner des salaires plus bas et des conditions de travail plus précaires pour les travailleurs.

- Contradiction entre la production pour l'accumulation et la production pour la satisfaction des besoins : Le capitalisme est motivé par le profit plutôt que par la satisfaction des besoins humains. Cela peut conduire à une surproduction de certaines marchandises et à une sous-production d'autres, créant ainsi des déséquilibres économiques.

Marx croyait que ces contradictions finiraient par mener à des crises économiques et sociales qui mettraient en évidence les failles du capitalisme et stimuleraient la conscience de classe du prolétariat, conduisant à une révolution et à l'établissement du socialisme.

Class struggles and communism

Marx believed that the revolution should be led by the workers themselves, once they had acquired class consciousness. This is a recognition of their common status and interests as an exploited class. This consciousness, he argued, would be stimulated by the contradictions inherent in capitalism, which would make the oppressive and exploitative nature of this system increasingly evident. This class consciousness is fundamental to Marxism, as it is seen as the motor of class struggle and revolution. Marx argued that only a conscious and united proletarian class could overthrow capitalism and establish communism. Communism, as envisaged by Marx, is a classless society where the means of production are held in common and goods are distributed according to the principle of "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need". In other words, he foresees a society where exploitation and class oppression are eliminated, where labour is freed from its capitalist constraints and where the needs of all are met.

For Marx, the transition from capitalism to communism would involve an intermediate phase of proletarian dictatorship, where workers would take control of the state and use it to eliminate the remnants of capitalism and build the foundations for communism. This phase would be characterised by a continuous struggle against the residues of the old social order and would be necessary to ensure the transition to a classless society.

For Marx, revolution was not simply a matter of changing leaders or redistributing existing wealth, but rather a process of radical transformation of the economic and social structure itself. He saw the state under capitalism as an instrument of the ruling class, used to maintain and perpetuate its power and control over economic resources. Consequently, he argued that workers could not simply take control of the existing state and use it for their own ends. Instead, they had to completely destroy this "state machine" and replace it with a new form of social organisation. In Marx's ideal, this new form would be a "dictatorship of the proletariat", a transitional period during which the workers would use the power of the state to eliminate the remnants of the capitalist class and rebuild society on a socialist basis. Ultimately, this dictatorship of the proletariat would lead to the establishment of communism, a classless, stateless society where the means of production are held in common. It is important to note that, for Marx, the ultimate goal was a classless and stateless society. The "dictatorship of the proletariat" was a necessary step towards this goal, but it was not an end in itself. In other words, the goal was not simply to replace one ruling class with another, but to eliminate the class system altogether.

The "Manifesto" Thesis

In the Manifesto, he describes the phases of revolution: "The first stage in the workers revolution is the constitution of the proletariat into a ruling class, the conquest of democracy. The proletariat will use its political domination to gradually wrest all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralize all the instruments of production in the hands of the state.

Measures for the State of the Proletariat :

- expropriation of land ownership: expropriation of the rich and possessing

- highly progressive tax

- abolition of inheritance: condemnation of capitalist dynasties

- confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels

- forfeiture of property to the Crown

- centralization of credit in the hands of the state

- multiplication of national factories and production instruments

- compulsory work for all;

- combination of agricultural and industrial work

- free public education for all children. There is a modern awareness of the need for a structured state that structures the social field. Modern elements appear in the analysis of the improvement of the functioning of society:

- the state: at the centre of the political process

- the organization of the proletariat into a dominant class

- transformation of production reports.

Marxism's dream is to achieve a classless society. When the bourgeoisie is eliminated is the reappropriated capital we must be able to arrive at a new society without classes and enemies. The criticism would be to say that Marx was wrong, he acquires a utopian dimension that does not take into account that the divergences, on the other hand the interests cannot necessarily be concordant, the power relations do not evaporate.

Of course, any class struggle is a political struggle. On the other hand, the revolution must be accepted in its capacity to destroy production capacity, but also in the violence it generates. Basically, we are in an interpretation that takes essence in Machiavelli's thought.

If there is no conflict in society, then the essence of politics must be rethought. It is a regulatory instrument that disappears without conflict.

So we can ask ourselves if there can be an administration of things without a policy?

When Marx says that every society has been marked by conflict, he puts forward the concept of structure. He postulates that every society is crossed by conflict.

Marx is a historian of civilizations and long periods, whatever the social, political and cultural nature of societies the problem arises. Marx postulates that there are structures that persist in societies, but are not necessarily visible, they give themselves in societies, but do not give themselves to be read immediately.

Structuralism

Claude Lévi-Strauss : 1908 - 2009

A philosopher, ethnologist and sociologist born in 1908, Claude Lévi-Strauss is a 20th century figure and one of the great founders of structuralist analysis.

He first studied philosophy and then ethnology. He then left for Brazil and in 1935 became professor of sociology at the University of Sao Paulo. Between 1935 and 1938, he studied the Indian tribes of the Amazon. His hypothesis is "the further I go, the more I can analyze what I live.

During the war, he went to the United States and began his thesis which he presented in 1949. This thesis is entitled Les structures élémentaires de la parenté. It is a reflection on the construction of related systems in Amazonian societies. Kinship logics are not random, they are programmed, it is a social organization a field of structure. Hence kinship is not of the order of freedom. The organizational constitution of a company is a kinship structure. All the reproduction of conscious and unconscious rules promotes the functioning of societies.

This is the first structuralist analysis of the social field between kinship and structure. Behind each individual case lies the structure of the sociological organization.

He acquired considerable influence and became the theoretician of structuralism. Returning to France, he brought together researchers from different fields, and in 1949 he became director of the practical school of social science studies at a chair of comparative religions. It is set up in a device where it will be able to work on the construction of the structures.

Behind Lévi-Strauss, there is a very complex stream of writing and structuralist scientific research. It is a reflection on the permanence of structures and their future. After his thesis, he produced a series of books which had a considerable influence on the analysis of myths. Myth is never a gratuitous object, it is a structuring narrative that produces a collective identity and builds a common future. Every society needs myths; from this myth, society produces its structure.

In 1958, he published Anthropologie structurale, in which he deployed all the elements of analysis of the different social fields of social organization and on how the fabrication of myths creates cohesion and coherence.

In the chapter on history and ethnology, he produces a critical vision that does not focus on particularity, but on structure as a form of timelessness. What interests her is that, at one point, it contains structures that can be compared. It produces a critique of ethnology and ethnography:

- Ethnology: observes and analyses human groups considered in their particularity. It establishes documents that can be used by the historian. For him, he is only studying the science of particularity.

- Ethnography: describes and analyses the differences that appear in the way they manifest themselves in different societies. He gathers the facts, and presents them according to requirements that are the same as those of the historian.

Then, he poses what he considers to be a more fundamental science of the origin of structuralism:

- Linguistics: can provide the sociologist, in the study of kinship problems, with assistance that makes it possible to establish links that were not immediately perceptible. Through the structures of language, it allows us to question ourselves about links that were not immediately perceptible.

- Sociology: can provide the linguist of customs with positive rules and prohibitions that make the persistence of certain cultural traits understandable.

Still in his book Anthropologie structurale, in his chapter on linguistics and anthropology, he states language as an architecture structuring the non-neutral social field that defines structural phenomena. Language can be considered as a product of culture; it sets out a structured way of functioning.

The idea is that rigorous methods of linguistics can be applied to social science methods. Since linguistics is the structural linguistics that states the conception of words.

Later, he offers another criticism by approaching the notion of archaism in ethnology. All recent history for a century and colonization have produced an antithetical discourse based on civilization on the one hand and the absence of culture on the other. All the discourse put in place since the 1830s is built around the notion of aid and not domination to bring to the peoples of undeveloped countries the power and culture of developed countries. Thus, Lévi-Strauss shows that it is necessary to revolutionize ideas, because what is called "primitive people" is by no means endowed with primitive behaviour, but on the contrary with structured social and political behaviour; they are not peoples without history, but peoples whose history itself escapes us in part because in many of these societies there is no transmission through the written word.

Thus, it produces a critique of archaism because it is necessary to manufacture new tools that can account for the weight of the structure

He then develops a passage on the sorcerer and his magic. It is no longer a question of thinking our modern societies on the principle of rationality, it is a question of returning to the structural weight that magic has in societies. Lévi-Strauss will work on what makes magic in a society and what its effectiveness is.

Basically, there are behaviours that can be explained by their social function in society. For René Girard, the sorcerer is endowed with an efficiency of rationality, because he is at the service of society and from a corpus of belief allows society to function; the sorcerer is not external to society, but he is fully actor, it is by this very fact an element of structure that makes social order.

For Lévi-Strauss, a myth is a story that presupposes an esoteric interpretation of the world, myths are a conceptualized way of thinking about the world where a structuralist interpretation appears. All traditional societies make myth and our contemporary societies will inherit these myths speaking timelessly of power. The value of a myth is its timelessness as a permanent structuralist narrative. Thus, they have no reason to disappear and reproduce.

If we look at the dimension of politics today, we realize that politics needs a sacred dimension of the function of politics necessary for its functioning. When the sacred is lost, there is no politics.

With Lévi-Strauss, we are in an area where structure is fundamental. The structure is of the decryption order, it does not reveal itself. Structuralist thinking makes it possible to analyse modes of society.

Marxist structuralism in the field of politics: Nicos Poulantzas (1936 - 1979)

As structuralism persists, a certain number of authors have sought to make the link between structuralism and Marxism, including Nico Poulantzas.

Poulantzas was a Marxist thinker and militant of the Greek Communist Party. He will draw heavily on Marx's analysis of fascisms and dictatorships, but also on questions of the link between political power and the state (political power and social classes). He had his hour of glory in the 1960s and 1970s.

Structuralist thinking without Marx could probably not have emerged, for he insists on thinking society and looking at society in a different way.

The thinking of the social sciences in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s was strongly marked by Marxism, because the issue of reflection in the social sciences was not detached from the problems of society, particularly from the paradigm of decolonization. In the 1950s and 1960s, the social sciences interacted with Marxism to understand the birth of these revolutionary struggles. In structuralism, there is a strong inspiration of Marxism without claiming it to the contrary of Poulantzas.

When he seeks to define the capitalist state, he will be interested in the construction of bourgeois domination in the authoritarian state. According to Poulantzas, the capitalist state is a "material condensation of power relations" between classes.

It describes a structuralist system of power organization that persists and is a tactical line of force that lives only by a very strong institutional structure. It will propose a structural-Marxist analysis on the concept of the national social state: the state participates in the constitution of social relations.

What characterizes the state crisis is a permanent crisis that makes the system work in order to make them work militarily. It extends the Marxist analysis, because we are in a mental and cultural pattern in the years 1950 - 1960 that has not changed in terms of structure including the structuring of the State. Thus, the State embodies this structuralist balance of power, the State is therefore no longer a regulator, but on the contrary a creator of divergences.

Although it is the engine of social action, the State only ratifies the social relations conceived by the dominant class. He did not regulate violence, he sought to reconcile Marxism and structuralism.

The state is a concentration of dominant forces. For Poulantzas, the constitution of authoritarian states can only be overthrown by popular struggle through revolution. Popular struggle makes it possible to define a strategic configuration for challenging these structures.

This thought is interesting, for he himself is caught up in his contradictions, for he thinks he can think things through, but the weight of structuralist thought draws on the side of the impossibility of interrupting it. He legitimizes violence as a natural act, even speaks of preventive counter-revolution as a measure of the state to defeat any revolution.

Annexes

- Texte intégral sur Marxist.org

- Fiche de lecture Manifeste du parti communiste

- Manifeste du Parti communiste K. Marx et F. Engels

References

- ↑ Differenz der demokritischen und epikureischen Naturphilosophie.