Marxism and Structuralism

La pensée sociale d'Émile Durkheim et Pierre Bourdieu ● Aux origines de la chute de la République de Weimar ● La pensée sociale de Max Weber et Vilfredo Pareto ● La notion de « concept » en sciences-sociales ● Histoire de la discipline de la science politique : théories et conceptions ● Marxisme et Structuralisme ● Fonctionnalisme et Systémisme ● Interactionnisme et Constructivisme ● Les théories de l’anthropologie politique ● Le débat des trois I : intérêts, institutions et idées ● La théorie du choix rationnel et l'analyse des intérêts en science politique ● Approche analytique des institutions en science politique ● L'étude des idées et idéologies dans la science politique ● Les théories de la guerre en science politique ● La Guerre : conceptions et évolutions ● La raison d’État ● État, souveraineté, mondialisation, gouvernance multiniveaux ● Les théories de la violence en science politique ● Welfare State et biopouvoir ● Analyse des régimes démocratiques et des processus de démocratisation ● Systèmes Électoraux : Mécanismes, Enjeux et Conséquences ● Le système de gouvernement des démocraties ● Morphologie des contestations ● L’action dans la théorie politique ● Introduction à la politique suisse ● Introduction au comportement politique ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : définition et cycle d'une politique publique ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : mise à l'agenda et formulation ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : mise en œuvre et évaluation ● Introduction à la sous-discipline des relations internationales

Marxism is a socio-economic theory and a method of socio-political analysis based on the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. It is mainly critical of capitalism and aims to replace it with communism, a classless society. Marxism asserts that all societies progress through class struggle, a confrontation between the ruling class and the oppressed classes. Structuralism, on the other hand, is a theoretical approach mainly used in the social sciences, the humanities, psychology, anthropology and linguistics. It focuses on understanding the underlying structures that determine or shape human behaviour, perception and meaning. Structuralists argue that reality can only be understood by examining the wider systems that shape individuals and events. Structuralo-Marxism is a school of thought that attempts to fuse the ideas of Marxism and structuralism. The aim is to understand how social and economic structures determine the behaviour and perceptions of individuals, while keeping in mind the class struggle and the role of capitalism in structuring these systems. Structural Marxists argue that capitalism is a structure in itself that shapes people's behaviour and perceptions.

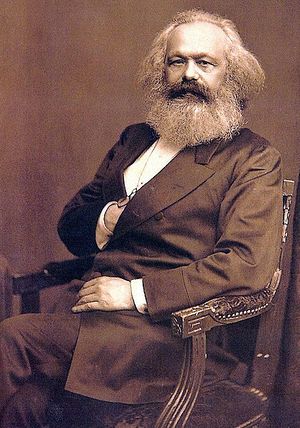

To structure our discussion, we will begin with an examination of Marxism, focusing on the contributions of its founder, Karl Marx. We then turn to structuralism, exploring in depth the work of the celebrated anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. Finally, we conclude by assessing the lasting influence of Marxist thought on the political sphere.

Marxism

Karl Marx : 1818 - 1883

Marx is a key personality of the 19th century. He will cross it, confronting the exceptional mutation of this century marked by the industrial revolution which goes beyond all the social, political and cultural frameworks of the old regime. We're being thrown into an upheaval that Marx is going to want to echo.

Born into a family of Jewish lawyers converted to Protestantism, he grew up in an easy and favorable environment that was not revolutionary, but conducive to intellectual development. He will combine three subjects: the law which enables him to understand that it is a science of the structuring of societies by its normative dimension which imprints society by its mode of functioning and regulation; history which offers a field of long duration to interpret events and phenomena. Rapidly, it will be marked by the readings of the first socialists. He then completed his studies in philosophy at the major universities of the time, Bohn and Berlin.

In 1841, Marx defended a doctoral thesis on Epicure[1]. Between 1841 and 1845, he began to absorb the first revolutionary doctrines that appeared and were already based on a revolutionary socialism that took into consideration a very hard world for work combined with a rise in power of capitalism called the "first capitalism". It is a capitalism of exploitation without social consideration of labour.

He lives in an environment that will quickly make him aware of political protest. Thus, from 1840, he became pre-revolutionary, being driven back from Prussia and France. In Germany, he became editor of the Rhineland Gazette, which got him into trouble, and as an opposition newspaper with a democratic and revolutionary tendency, as editor-in-chief he participated in the German revolutionary effervescence.

The history of Marx is the constitution of the revolutionary international. The emergence of the capitalist society sees the emergence of a diaspora of intellectuals and thinkers scattered in the great capitals that organize themselves, allowing the development of revolutionary thought.

In Paris, he met Engels, who was campaigning and reflecting on a number of reforms to be introduced. Thus, Marx will develop a revolutionary proletarian socialist theory that legitimizes violence; violence is an element of combat; the question of social violence is legitimate. The only way to transform society is to propose revolution. He is brought to justice and goes to Belgium from where he will also be expelled.

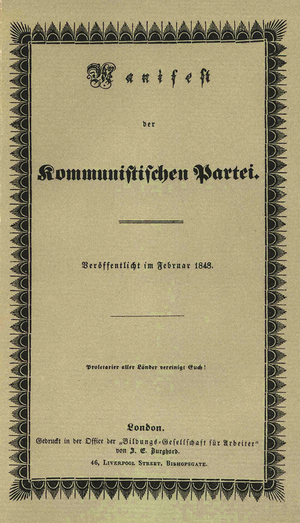

Starting from the Communist Party Manifesto in 1867, he began to question one of the major components of capitalism, as Weber had understood in his book on Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism, that in order to understand capitalism, one must integrate the question of capital.

For many years Marx wrote Le Capital until its publication in 1867. It revolves around a new specific vocabulary which is the concept of political economy. Economics is not outside politics, it conforms to and describes a political system. In other words, the economy is not outside society, but it is the basic premise that the economy is an integral part of society. Political economy links economic issues to the systems that regulate them.

Marx was delighted with the revolution of 1848 in France and the social conflicts that were born, all signs of the transformation of society through revolution.

From 1864 onwards, he was part of the International Socialist Workers' Party of which he was an eminent member. This movement will organize the pre-revolutionary socialist movements.

After Le Capital, he will ask himself about the commune. Finally, he will examine the relations between social classes and capital as well as the challenge of a collective struggle at the level of the European peoples.

Classes and class struggles

[[Fichier:Pyramid of Capitalist System.png|thumb|« Pyramid of Capitalist System », early 20th century.]

]Marx was a very versatile thinker. His work spanned many fields, including philosophy, sociology, economics and politics. His critique of capitalism, as set out in works such as "Capital", is still influential and relevant today. We must first start with an apriori from the Manifesto, saying that "the history of all society up to the present day has been the history of class struggles". This quote is from the "Manifesto of the Communist Party", co-authored by Marx and Friedrich Engels. It is one of Marx's most famous statements, which sums up his view of history as a series of class conflicts. According to him, all society is structured around the relations of production - the relations between those who own the means of production (the bourgeoisie) and those who sell their labour power (the proletariat). This dynamic creates an inherent conflict, a class struggle, which is the engine of social and historical change.

Marxism, as a theory, is therefore deeply concerned with questions of power, control and conflict in the economic context. For Marx, the economy is not a separate sphere from social and political life, but is intrinsically linked to it. Capitalism, as an economic system, shapes and is shaped by social and political structures. This understanding of the interconnectedness of economics, politics and society makes Marx not only an economist or political philosopher, but also a revolutionary social theorist.

For Marx, a class is defined not only by its relation to the means of production, but also by its class consciousness - a shared understanding of its position in the capitalist system of production and its interests in opposition to those of other classes. This class consciousness is not automatic or natural, but is the product of lived experience and struggle. In "Capital", Marx talks about the process by which workers, who are initially in competition with each other in the labour market, begin to recognise that they share a common position and common interests in opposition to those of the bourgeoisie. This process of awareness and solidarity formation allows for the formation of a class as a political force. However, Marx also pointed out that the bourgeoisie uses various strategies to prevent working class consciousness, such as dividing workers along racial, ethnic or gender lines, or spreading ideologies that justify and naturalise class inequality. This idea was later developed by Marxist theorists such as Antonio Gramsci, who spoke of the cultural hegemony of the bourgeoisie. Thus, for Marx, the class struggle is not only an economic struggle, but also an ideological and cultural struggle. It is a struggle for class consciousness, for the recognition of common interests and for collective organisation for social change.

Marx argued that different classes have fundamentally divergent economic interests in a capitalist society that lead to antagonistic goals. For example, the bourgeoisie, which owns the means of production, seeks to maximise its profits. This can be achieved by reducing the costs of production, which often includes reducing wages or extending working hours for the working class. On the other hand, the proletariat, which sells its labour power, has a direct interest in raising wages and improving working conditions. These divergent interests are intrinsic to the capitalist system and lead to a constant struggle between the classes. These class antagonisms limit the possible actions of each class. For example, the working class is limited in its actions by the need to sell its labour power in order to survive, while the bourgeoisie is limited by the need to maximise profits to remain competitive in the capitalist market. Furthermore, these class antagonisms also shape the political field. According to Marx, the state under capitalism generally acts in the interests of the bourgeoisie and seeks to maintain the existing class order. This means that attempts by the working class to change the system are often met with resistance from the state and the ruling class. For Marx, class struggle is not only a characteristic of capitalism, but also a barrier to action, as it reflects divergent and antagonistic interests between different social classes.

For Marx, class struggle is the motor of history and social evolution. Society is not a harmonious collection of individuals with convergent interests, but rather is marked by fundamental conflicts and class antagonisms. Class struggle is not only an economic reality, but also a social and political reality. It shapes people's consciousness, their identity and their understanding of the world. By confronting exploitation and class oppression, individuals begin to develop a class consciousness - an understanding of their common position and common interests as a class. This class consciousness can lead to collective organisation and resistance, and ultimately to the transformation of society. However, class society does not simply disappear with the announcement of formal freedom or equal rights. On the contrary, class society persists and continues to structure social, economic and political life, even in modern societies that present themselves as free and equal. For Marx, class struggle is both the product of class society and the means by which that society can be transformed. It is a profoundly conflictual and dynamic worldview, which emphasises the role of struggle, resistance and change in human history.

"Modern bourgeois society (...) has not abolished class antagonisms. It has merely substituted new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle for those of the past. This quote comes from Marx and Engels' "Manifesto of the Communist Party", and it summarises an important part of their analysis. According to them, the bourgeois revolution - that is, the transition from feudalism to capitalism that took place in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries - did not abolish class antagonisms, but rather transformed their nature. In feudal society, the main classes were nobles and serfs. With the advent of capitalism, these classes were replaced by the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The bourgeoisie, as the class that owns the means of production, became the new dominant class, while the proletariat, which sells its labour power to the bourgeoisie, became the new oppressed class. However, even though the precise nature of class oppression and domination changed, Marx and Engels argued that the fundamental antagonism between classes remained. Capitalism, like feudalism, is based on the exploitation of the working class by the ruling class. Moreover, Marx and Engels argued that capitalism has in fact exacerbated class antagonisms. Capitalism is characterised by extreme class inequality and inherent instability, with recurrent economic crises exacerbating the class struggle. This is why they argued that capitalism would eventually be replaced by communism, a classless society where the means of production would be collectively controlled.

Capital and salaried labour

The movement of capital

For Marx, the bourgeoisie is defined by its relationship to the means of production - it owns and controls the factories, machines, land and other means of production that are needed to produce goods and services. The working class, on the other hand, does not own these means of production and therefore has to sell its labour power to the bourgeoisie in exchange for a wage. According to Marx, the main goal of the bourgeoisie is the accumulation of capital. This means that it constantly seeks to increase its wealth by maximising profits and minimising costs. One of the main ways to achieve this is to exploit the labour power of the working class. Workers are paid less than the full value of what they produce, and the difference (what Marx calls 'surplus value') is retained by the bourgeoisie in the form of profits. From this perspective, the bourgeoisie has no particular interest in the welfare of the working class, except insofar as it affects its ability to produce surplus-value. Consequently, there can be a constant tension between the bourgeoisie and the working class, as the former seeks to maximise its profits while the latter seeks to improve its wages and working conditions. It is this tension, this class struggle, which is at the heart of Marx's view of capitalism. For him, capitalism is a system of exploitation that creates inherent inequalities and class conflicts. And it is this class struggle that, according to him, would ultimately be the motor of social transformation and the transition to a classless society.

For Marx, capital is not simply a sum of money or a stock of goods. Instead, he defines it as "value in process" or "self-increasing value". In the capitalist system, capital is invested in the purchase of means of production (machinery, raw materials, etc.) and labour power. These elements are then used to produce goods or services which are sold on the market. The value of these goods or services is greater than the sum of the value of the means of production and labour power initially purchased. This difference is what Marx calls "surplus value", and it is the source of capitalist profit. In this process, there is a clear division between the owners of capital (the bourgeoisie) and those who sell their labour power (the proletariat). The bourgeoisie uses its capital to generate more value, while the proletariat is paid a value (in the form of wages) that is less than the value it produces. It is this extraction of surplus value from the working class that, according to Marx, constitutes the exploitation at the heart of capitalism. Thus, for Marx, the ultimate goal of capital and its owners is not simply the production of goods or services, but the accumulation of more value. This is what motivates the capitalist system and is also the source of its contradictions and crises.

The origin of the surplus value

For Marx, the objective of the capitalist is not simply to produce goods or services, but to generate surplus value. This surplus value is the difference between the total value of the goods or services produced and the value of the inputs used for their production, including labour power. In the capitalist system, this surplus value is constantly reinvested to generate even more value. This is what Marx calls capital accumulation. It is a never-ending process, where money is invested to generate more money. This dynamic of perpetual accumulation is at the heart of the capitalist system. It leads to constant economic growth, but also to increasing inequality, as surplus value is appropriated by the capitalists rather than by the workers who produce it. Moreover, this dynamic of perpetual accumulation can also lead to economic crises, as the constant search for surplus value can lead to overproduction and economic instability. For Marx, capital is not simply a sum of money or a stock of goods. It is a social relation based on exploitation, where surplus value is extracted from workers' labour and reinvested to produce even more value.

In the capitalist system, surplus value - that is, the value created by labour beyond what is necessary to sustain the worker - is appropriated by the capitalist rather than redistributed to the workers. The capitalist then reinvests this surplus value to generate even more capital, in a process Marx calls "capitalist accumulation". This accumulation of capital leads to an increasing concentration of wealth in the hands of a small elite of capitalists, while the majority of workers remain relatively poor. This creates ever greater inequality in society. Moreover, this accumulation of capital does not necessarily benefit society as a whole. For example, it can lead to overproduction of goods, economic crises, and increased exploitation of workers. For Marx, the capitalist system is inherently unequal and unstable. He argued that the only way to solve these problems would be to replace capitalism with communism, a system in which the means of production are controlled collectively by the workers themselves.

Work and overwork

It is possible to highlight two key concepts in Marxist economics: constant and variable capital, and the two forms of surplus value - absolute and relative surplus value.

Constant capital, as you mentioned, includes the non-human means of production such as machines, factories and raw materials. This capital does not create new value in itself, but transfers its own value to the finished products.

Variable capital, on the other hand, is the part of capital used to pay for labour. This capital is called 'variable' because it is capable of producing new value beyond its own value. That is, workers are able to produce more value than they receive in the form of wages.

Absolute surplus value is generated by extending the working day. If a worker can produce enough to cover his wage in five hours, but works ten hours, then the extra five hours of unpaid work generates absolute surplus value for the capitalist.

Relative surplus-value, on the other hand, is generated by reducing the labour time needed to produce a commodity, usually through technological innovation or improved efficiency. If a worker can produce a commodity in two hours rather than four, then the value of that commodity falls and the capitalist's relative surplus value rises.

Finally, Marx sees these processes as having limits. There is a limit to the length of the working day and to a worker's capacity to work. Similarly, there is a limit to the amount of relative surplus-value that can be generated through improved efficiency. These limits, according to Marx, are sources of tension and conflict in the capitalist system.

Accumulation

There are two major results of capital accumulation according to Marx: the concentration of capital and the creation of an overpopulation of workers.

- Concentration of capital: According to Marx, the process of capital accumulation inevitably leads to an increasing concentration of wealth and economic power. In other words, more and more capital ends up in the hands of fewer and fewer capitalists. This creates a fundamental contradiction in the capitalist system, because although capitalism is based on the idea of competition, its functioning tends to destroy this competition by favouring the formation of monopolies.

- The creation of an overpopulation of workers: Marx also argues that the process of capital accumulation leads to the creation of an "industrial reserve army" of unemployed workers. This is due to the constant improvement of technology and efficiency, which allows capitalists to produce more with fewer workers. This overpopulation of workers serves to keep wages down, as there is always a reserve of workers ready to take the place of those who demand higher wages.

Ultimately, Marx sees these tendencies as leading to an intensification of class conflict and, ultimately, to revolution. He argues that the proletariat, which is both oppressed by capitalism and vital to its functioning, has both the interest and the power to overthrow the capitalist system and replace it with communism.

The contradictions of capitalism

Marx soutient que le capitalisme contient des contradictions inhérentes qui, selon lui, mèneront finalement à sa propre déconstruction. Ces contradictions sont principalement le résultat de la dichotomie entre le capital et le travail dans une économie capitaliste. Voici comment il voit ces contradictions :

- Contradiction entre le capital et le travail : Le capitalisme repose sur la relation entre les capitalistes, qui possèdent les moyens de production, et les travailleurs, qui vendent leur force de travail en échange d'un salaire. Selon Marx, cette relation est fondamentalement conflictuelle car les intérêts des capitalistes et des travailleurs sont diamétralement opposés. Les capitalistes cherchent à maximiser les profits en minimisant les salaires et en maximisant le temps de travail, tandis que les travailleurs cherchent à maximiser leurs salaires et à minimiser leur temps de travail.

- Contradiction entre l'accumulation du capital et la surpopulation relative : Comme vous l'avez mentionné précédemment, l'accumulation du capital entraîne une concentration de la richesse et une surpopulation relative de travailleurs. Cela crée une tension car il y a une offre excessive de main-d'œuvre par rapport à la demande, ce qui peut entraîner des salaires plus bas et des conditions de travail plus précaires pour les travailleurs.

- Contradiction entre la production pour l'accumulation et la production pour la satisfaction des besoins : Le capitalisme est motivé par le profit plutôt que par la satisfaction des besoins humains. Cela peut conduire à une surproduction de certaines marchandises et à une sous-production d'autres, créant ainsi des déséquilibres économiques.

Marx croyait que ces contradictions finiraient par mener à des crises économiques et sociales qui mettraient en évidence les failles du capitalisme et stimuleraient la conscience de classe du prolétariat, conduisant à une révolution et à l'établissement du socialisme.

Class struggles and communism

Marx believed that the revolution should be led by the workers themselves, once they had acquired class consciousness. This is a recognition of their common status and interests as an exploited class. This consciousness, he argued, would be stimulated by the contradictions inherent in capitalism, which would make the oppressive and exploitative nature of this system increasingly evident. This class consciousness is fundamental to Marxism, as it is seen as the motor of class struggle and revolution. Marx argued that only a conscious and united proletarian class could overthrow capitalism and establish communism. Communism, as envisaged by Marx, is a classless society where the means of production are held in common and goods are distributed according to the principle of "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need". In other words, he foresees a society where exploitation and class oppression are eliminated, where labour is freed from its capitalist constraints and where the needs of all are met.

For Marx, the transition from capitalism to communism would involve an intermediate phase of proletarian dictatorship, where workers would take control of the state and use it to eliminate the remnants of capitalism and build the foundations for communism. This phase would be characterised by a continuous struggle against the residues of the old social order and would be necessary to ensure the transition to a classless society.

For Marx, revolution was not simply a matter of changing leaders or redistributing existing wealth, but rather a process of radical transformation of the economic and social structure itself. He saw the state under capitalism as an instrument of the ruling class, used to maintain and perpetuate its power and control over economic resources. Consequently, he argued that workers could not simply take control of the existing state and use it for their own ends. Instead, they had to completely destroy this "state machine" and replace it with a new form of social organisation. In Marx's ideal, this new form would be a "dictatorship of the proletariat", a transitional period during which the workers would use the power of the state to eliminate the remnants of the capitalist class and rebuild society on a socialist basis. Ultimately, this dictatorship of the proletariat would lead to the establishment of communism, a classless, stateless society where the means of production are held in common. It is important to note that, for Marx, the ultimate goal was a classless and stateless society. The "dictatorship of the proletariat" was a necessary step towards this goal, but it was not an end in itself. In other words, the goal was not simply to replace one ruling class with another, but to eliminate the class system altogether.

The "Manifesto" Thesis

Marx envisaged a revolution in several stages, where the proletariat, the working class, would take control of the state and use this power to transform society: "The first stage in the workers' revolution is the constitution of the proletariat as the ruling class, the conquest of democracy. The proletariat will use its political domination to wrest all the capital from the bourgeoisie little by little, to centralise all the instruments of production in the hands of the state".

The first step, according to him, would be for the proletariat to organise and constitute itself as a ruling class. This means that the workers must unite, become aware of their common status and interests as an exploited class, and overthrow the bourgeoisie through revolution. Marx believed that this takeover could be achieved democratically, although he recognised that the bourgeoisie might not surrender without a struggle. Once in power, the proletariat would use its political dominance to begin dismantling the capitalist system. This would involve gradually wresting all capital from the bourgeoisie and centralising all the instruments of production in the hands of the state. In other words, the means of production would be taken out of the hands of the private capitalists and placed under the control of the state, which would then be under the control of the proletariat.

The aim of these measures would be to eliminate capitalist exploitation and create a planned economy where production is directed to meet the needs of all rather than the profit of a few. This is a step towards the establishment of communism, where, according to Marx, the state itself would eventually wither away to make way for a classless, stateless society.

Marx and Engels set out in the Communist Manifesto a list of measures that the proletariat, once in power, should implement to transform capitalist society into a communist society. These included:

- Expropriation of land ownership and application of land rent to state expenditure: This means the end of private ownership of land and the use of the income from it to finance the state.

- A highly progressive tax: This means a tax whose rate increases with income or wealth, which would hit the richest hardest.

- Abolition of inheritance: This would prevent wealth from being passed on from generation to generation and concentrated in a few families.

- Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels: This would eliminate opposition to the new regime.

- Centralization of credit in the hands of the state: This means that the state would control all financial institutions and financial resources.

- Centralisation of transport and communication in the hands of the state: This means that the state would control all means of transport and communication.

- Multiplication of state-owned factories and instruments of production: This means an expansion of production under public control.

- Compulsory work for all: This means that everyone would be required to work and contribute to production.

- Combination of agricultural and industrial labour: This means the abolition of the division between urban and rural labour.

- Free public education for all children: This means that education would be a right for all and not a privilege for a few.

These measures, according to Marx and Engels, would end capitalist exploitation and create a society where production is controlled by the working class and used for the benefit of all.

The ultimate goal of Marxism is to achieve a classless society, where resources are owned and controlled by the community as a whole and where there is no exploitation. This is a vision that has been criticised in many ways. Firstly, some argue that the Marxist view overlooks human nature and individual differences. They argue that people have different ambitions, talents and desires, and that these differences will always result in inequalities of power and wealth. They also argue that people have a natural inclination to own and control private property. Secondly, there are those who argue that the Marxist vision is too idealised and lacks realism. They argue that a classless society is a utopian goal that cannot be achieved in the real world. They argue that even in societies that have attempted to implement Marxism, new classes and new forms of exploitation have emerged. Thirdly, some critics argue that the Marxist view neglects the need for power and authority structures. They argue that in order to organise a society and maintain order, certain forms of hierarchy and power are necessary. They also suggest that without these structures there could be chaos and anarchy.

Marxist thought accepts that all class struggle is inherently a political struggle, and it recognises that a revolution, necessary to overthrow the existing class structure, may involve a certain amount of destruction and violence. This perspective is indeed in line with certain aspects of Machiavelli's political thought. Machiavelli, an Italian political philosopher of the Renaissance, wrote about the dynamics of power and the means necessary to acquire and retain it. He argued that politics is essentially a realm of conflict and struggle, and that rulers must be prepared to use any means necessary, including violence, to maintain their power. Similarly, Marx saw the class struggle as a struggle for political power, where the proletariat must overthrow the bourgeoisie through revolution to establish a new social structure. This may involve a certain amount of destruction, especially of the existing economic infrastructure, and violence. However, unlike Machiavelli, Marx's ultimate goal is not the retention of power for any individual or group, but rather the creation of a classless society where power is shared equally.

The question of whether there can be an 'administration of things' without politics is at the heart of the debate on the nature and role of politics in society. In the Marxist view, the final phase of communism is a classless society in which the state, as a tool of class domination, would fade away and be replaced by a more egalitarian form of social organisation. Marx and Engels used the term "administration of things" to describe this society. In this vision, social and economic affairs are managed rationally for the benefit of all, without the need for political struggle for resources and power. However, this vision has been criticised. Some argue that politics is inevitable because societies are always faced with decisions about the distribution of resources and social priorities. These decisions inevitably involve conflicts of interest and disagreement, requiring some form of politics to resolve them. Furthermore, some point out that even if a society can eliminate economic classes, other forms of hierarchy and social differentiation may remain, creating new forms of political conflict. Finally, others question the idea that the administration of things can be totally neutral or rational, arguing that all decisions involve values and choices that are inherently political.

In Marxist theory, the structure of society is defined by the relations of production and the conflicts that arise from them. Marx argued that the economic system (the mode of production) determines the social structure, including the relations between classes. These relations are marked by inherent conflicts and power struggles. In simple terms, Marx argued that every society is structured around its economic system. For example, a feudal society is structured around the relations between lords and serfs, while a capitalist society is structured around the relations between the bourgeoisie (those who own the means of production) and the proletariat (those who sell their labour). The concept of 'conflict' is central to this perspective. Marx argued that conflict between classes is a driving force of social and historical change. These conflicts are inherent in the economic structure of society and can ultimately lead to radical changes in the structure of society - for example, through a revolution where the working class overthrows the bourgeoisie and establishes a new form of society.

Marx postulated that class conflict is a universal feature of human societies, although the specific forms of this conflict may vary according to historical and cultural circumstances. In primitive societies, Marx and Engels suggested that there was a 'primitive' form of communism, where resources were shared and there were no distinct classes. However, they also suggested that the development of private property and agriculture led to the emergence of social classes and the domination of one class over another, leading to class conflict. Marx's central point is that these class structures are often hidden or 'naturalised' in society, so that they appear to be natural and inevitable features of human life rather than social constructions that can be changed. It is here that the link with structuralism becomes apparent: like the structuralists, Marx sought to reveal the underlying structures that shape social life, even if they are not immediately apparent or recognised by those who live within them.

Structuralism

Claude Lévi-Strauss : 1908 - 2009

Claude Lévi-Strauss brought a unique perspective to sociology and anthropology with his structuralist approach. Structuralism, as a theory, proposes that human phenomena can only be understood as parts of a larger system, or structures. According to Lévi-Strauss, these structures are universal and can be revealed through the analysis of myths, rites, customs and other cultural aspects. His work on the indigenous tribes of the Amazon provided an important basis for the development of his theories. Lévi-Strauss argued that, even in these apparently simple and remote societies, there are complex structures of thought that inform their behaviour and culture. Far from being 'primitive', these societies possess a complexity and intellectual sophistication that the West has often overlooked or misunderstood. Lévi-Strauss adopted a comparative and cross-cultural approach to research, looking for similarities and differences between different cultures in order to understand the universal structures underlying human thought and behaviour. By going 'deeper', he was able to analyse the deepest elements of human culture and thought, often hidden or ignored in modern Western societies.

Claude Lévi-Strauss is famous for his studies of Indian tribes in the Amazon conducted between 1935 and 1938. He used an ethnographic approach to understand these cultures, living among them and observing their daily practices and beliefs. His famous quote, "the further I go, the more I can analyse what I experience", sums up his research philosophy: he believed that to truly understand a culture, one had to immerse oneself completely in it, live like its members and observe from the inside. Through this approach, Lévi-Strauss was able to explore and document in depth the customs, beliefs and social practices of these tribes, providing valuable insight into their ways of life. He also used these experiences to develop his structuralist theories, arguing that all cultures share certain underlying structures, despite their superficial differences. These experiences in Brazil had a major influence on his later work and helped establish his reputation as one of the most influential thinkers in 20th century anthropology. His work profoundly influenced not only anthropology, but also sociology, philosophy, history, psychology and other disciplines related to the humanities.

During the war, he went to the United States and began his thesis, which he presented in 1949. In this thesis, entitled "Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté", Lévi-Strauss approached the study of kinship systems in primitive and advanced societies from a structuralist perspective. According to him, kinship is not simply a matter of biology or blood relations, but is also determined by cultural norms and rules. These rules govern not only who is considered a relative, but also the behaviours and obligations that are expected from these relationships. Lévi-Strauss developed the idea that these kinship systems are structures, in the sense that they are composed of fixed and organised relationships that are maintained over time. He argues that these structures are universal, in the sense that they are present in all societies, even though the specific details of these structures may vary from culture to culture. According to Lévi-Strauss, these kinship structures are fundamental to the functioning of societies. They determine important aspects of social life, such as who can marry whom, how property is passed on from one generation to the next, and what the obligations and responsibilities of everyone in society are. Therefore, understanding these kinship structures is essential for understanding society itself.

Claude Lévi-Strauss pioneered the structuralist approach in anthropology, applying the method to a variety of social and cultural subjects. This approach assumes that each element of a society (e.g. rituals, customs, institutions, kinship rules, etc.) only makes sense in the context of the larger structure in which it is embedded. In the case of kinship systems, for example, Lévi-Strauss argued that specific rules and individual relationships can only be fully understood by situating them within the larger kinship structure of society. This structure, he argued, is based on exchange and reciprocity, and aims to promote cooperation and social harmony. Thus, for Lévi-Strauss, structure is fundamental at all levels of social and cultural organisation. It is what gives form and meaning to social relations and activities. It is also what allows anthropologists to understand and explain the similarities and differences between different cultures. He acquired considerable influence and became the theorist of structuralism. Returning to France, he brought together researchers from different fields, and in 1949 he became director of the Ecole Pratique des Etudes en Sciences Sociales with a chair in comparative religions. He was put in a position where he could work on the construction of structures.

For Claude Lévi-Strauss, myths are a form of symbolic communication deeply rooted in the human mental structure. They are fundamental elements of culture that provide models of thought and action, allowing people to make sense of the world and their place in it. Lévi-Strauss developed a distinctive approach to the analysis of myths, known as 'mythological structuralism'. According to this approach, all myths can be broken down into a set of smaller myths, or 'myths', which are the basic units of myth. These myths are organised in pairs of binary oppositions, reflecting the fundamental tensions and contradictions of social and cultural life. By collecting and comparing myths from different cultures, Lévi-Strauss sought to reveal the universal structures of human thought. He argued that, although the specific details of myths may vary from culture to culture, the underlying structures are remarkably similar, reflecting universal patterns of thought. In other words, for Levi-Strauss, myths are not simply stories that people tell for entertainment or to explain the world. They are essential tools that allow people to understand, navigate and make sense of their social and cultural reality.

Lévi-Strauss' Structural Anthropology

In his book "Structural Anthropology" (1958), Claude Lévi-Strauss proposes a revolutionary approach to anthropology based on the idea that all societies, regardless of their level of technology or specific cultural history, share common underlying structures of thought. He uses this approach to examine a range of cultural phenomena, from kinship systems to myths and rituals, and argues that these phenomena can be better understood by analysing them in terms of their underlying structures rather than by focusing on their manifest contents. For Lévi-Strauss, myths are particularly important because they express in a symbolic way the fundamental mental structures of a culture. Myths are not simply invented stories, but symbolic representations of the fundamental problems and concerns of a society. In "Structural Anthropology", Lévi-Strauss illustrates his approach with a detailed analysis of various myths from cultures around the world. He demonstrates that, despite their apparent diversity, these myths share common thought structures, thus revealing the existence of universal patterns of human thought. This approach had a profound impact on anthropology and other social science disciplines, and led to the emergence of the structuralist movement, which dominated much of social and cultural theory in the 1960s and 1970s.

Claude Lévi-Strauss emphasised the importance of structure over particularity in the study of human societies. He criticised the way ethnology and ethnography traditionally focused on the cultural and historical specificities of different societies, and argued that this approach neglected the common underlying structures that shape all human societies.

Ethnology, according to Lévi-Strauss, focuses on the documentation and analysis of the specific characteristics of different human groups. It is a discipline that collects information about the customs, traditions and social practices of different groups and presents them in a descriptive way. On the other hand, ethnography is a research method involving direct and participatory observation of cultural practices within a specific society.

Lévi-Strauss argued that both disciplines, while important, were limited by their emphasis on particularity. Instead, he advocated a structuralist approach, which sought to identify and analyse the universal structures of human thought that underlie all societies. He argued that it is by understanding these universal structures that we can truly understand the nature of human culture and society.

Linguistics and sociology were two disciplines that strongly influenced Claude Lévi-Strauss' thinking and the development of structuralism. According to Lévi-Strauss, these disciplines can work together to provide a deeper understanding of the structure of human societies.

- Linguistics: Lévi-Strauss was strongly influenced by structural linguistics, in particular by the work of Ferdinand de Saussure. For Saussure, language is not a set of words corresponding to things, but a system of signs in which each sign derives its meaning from its relationship with other signs. Lévi-Strauss applied this concept to anthropology, suggesting that elements of culture (e.g. rules of kinship, myths, rituals) can be understood as signs in a structured cultural system.

- Sociology: Lévi-Strauss was also influenced by Emile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, who emphasised the importance of social structures in the formation of culture and society. Lévi-Strauss used sociological concepts to analyse kinship structures, marriage rules and taboos in different societies, demonstrating how these social structures shape cultural life.

For Lévi-Strauss, linguistics and sociology are thus two complementary tools in the study of the structures underlying human culture and society.

Role of structural linguistics in Lévi-Strauss' structural anthropology

Claude Lévi-Strauss drew heavily on structural linguistics, particularly the work of Ferdinand de Saussure, to develop his approach to structural anthropology. According to Saussure, the meaning of a linguistic sign (a word, for example) depends on its system of relations with other signs within the overall structure of language, and not on its direct correspondence with an external reality. Lévi-Strauss applied this approach to anthropology. For him, the elements of a culture - be it myths, rituals, rules of kinship, etc. - are like linguistic signs. - Their meaning depends on the way they are used. Their meaning depends on how they relate to each other within the overall system of the culture, not on their direct correspondence with an external reality. In this sense, Lévi-Strauss sees language as a kind of "structure of structures". It serves as a model for understanding how other elements of culture are structured and interconnected. For example, just as the sounds of language are organised into words, words into sentences, and sentences into discourse, the elements of culture are organised into increasingly complex structures. It is for this reason that Lévi-Strauss sees linguistics as a key discipline for anthropology. The methods of structural linguistics - the analysis of systems of relations between signs - can be used to analyse the structures of culture.

Claude Lévi-Strauss challenged the idea that there is a linear hierarchy of cultures, from "primitive" to "advanced".

Claude Lévi-Strauss challenged the idea that there is a linear hierarchy of cultures, from "primitive" to "advanced". For him, all cultures are complex systems of meaning, and each must be understood in terms of its own internal logic, not by comparison with others. This perspective marked a major break with earlier anthropological approaches, which tended to judge non-Western cultures according to Western criteria. Lévi-Strauss emphasised that what are commonly referred to as 'primitive peoples' have complex and structured social and political systems. He rejected the idea that these societies are 'without history' simply because they have no written tradition. Instead, he argued that their history can be decoded from their myths, rituals and kinship systems, all of which carry historical meaning. Furthermore, Lévi-Strauss criticised the Eurocentric view that development and progress are a one-way street leading to Western modernity. He emphasised that each culture has its own developmental trajectory, which is shaped by its particular conditions and its own internal logics. This perspective helped to challenge ethnocentrism in anthropological studies and to promote a more equitable and respectful appreciation of cultural diversities.

Claude Lévi-Strauss was sceptical of the notion of archaism, as it implies a linear and progressive view of history, where 'archaic' societies are seen as lagging behind 'modern' ones. He criticised this perspective as Eurocentric and distorting. Instead, Lévi-Strauss proposed a structuralist approach, which seeks to understand each culture in terms of its own internal structures of meaning. Rather than judging societies according to a linear scale of development, he sought to identify the underlying systems of thought and meaning that shape social and cultural life. Consequently, Lévi-Strauss emphasised the importance of developing new theoretical and methodological tools to understand the complexity and diversity of human cultures. He argued that we must be able to recognise and respect the different internal logics that structure different societies, rather than judging them by our own cultural standards.

The importance of magic, myth and ritual in societies

In his work, Claude Lévi-Strauss has indeed emphasised the importance of magic, myth and ritual in societies, including modern ones. Far from considering them as irrational or primitive forms of thought, he argued that they play a crucial role in structuring social and cultural life.

Lévi-Strauss studied myths and rituals as forms of symbolic language. For him, these forms of communication are similar to language in that they are based on sign systems that are used to express ideas and feelings. Like language, they are structured by rules and conventions that allow individuals to share common meanings.

In his analysis of magic, Lévi-Strauss argued that magic, like science, is a form of knowledge that is based on logical systems of thought. He argued that magic is effective not because it involves supernatural forces, but because it allows individuals to structure their understanding of the world and act accordingly. In this sense, magic plays a crucial role in social and cultural life, helping individuals to make sense of their experience and navigate the world around them.

Lévi-Strauss's approach is consistent with that of René Girard in that both see the figure of the sorcerer as a structuring element of society. For Lévi-Strauss, the sorcerer, like myth or ritual, participates in the construction of the social structure by offering a framework for understanding and interpreting the world. The rites and beliefs associated with the figure of the sorcerer provide a kind of symbolic language through which individuals can make sense of their experience and navigate the world. René Girard, on the other hand, has developed a theory of mimetic desire to explain human behaviour and the functioning of societies. According to Girard, the sorcerer plays a key role in managing the tensions and conflicts that can arise in society as a result of this mimetic desire. The sorcerer, as an authority figure, can help to channel these tensions and maintain social order. Thus, as for Lévi-Strauss, the sorcerer is for Girard an essential structural element in the functioning of society.

Myth and politics

For Claude Lévi-Strauss, myths are stories that offer a symbolic and structured interpretation of the world. They are constitutive elements of cultures and societies, and serve to explain origins, values, beliefs, social structures and natural phenomena. Lévi-Strauss argued that all myths, whether from traditional or modern societies, share a common structure. He used an approach called structuralism to analyse myths. According to this approach, myths are built around pairs of binary oppositions (e.g. life/death, culture/nature), and these oppositions help to organise and make sense of human experience. Furthermore, Lévi-Strauss argued that myths are timeless: they are constantly reinterpreted and adapted to meet the current concerns of a society, but their basic structure remains the same. Thus, although the specific details of a myth may change over time, its structural framework and its role as a means of interpreting the world remain constant.

The idea that the political requires a certain dimension of the sacred can be understood in several ways.

- The political as sacred: Here, 'sacred' can be interpreted as something that is of ultimate importance, worthy of respect and veneration. From this perspective, political institutions, laws and values (such as democracy, justice, equality, etc.) can be considered sacred. They are essential for the functioning of society and the promotion of common welfare.

- Politics requiring the sacred: On the other hand, some might argue that politics needs a dimension of the sacred to legitimise its power and inspire allegiance and obedience from citizens. This could take the form of symbols, rituals and traditions that reinforce the authority of the state and national identity.

- The disappearance of the sacred and its impact on politics: In the absence of a sense of the sacred, some argue that politics can become purely technocratic, focused on efficiency and effectiveness rather than on values and principles. This could lead to political disillusionment and disaffection, and eventually the disintegration of the social fabric.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, as one of the founders of the structuralist approach in anthropology and the social sciences, emphasised the importance of underlying structures in understanding human societies. He used the idea of structures to analyse different aspects of human cultures, from kinship systems to myths, rituals and customs.

According to Lévi-Strauss, structures are not always immediately visible or obvious. They are often hidden beneath the surface, but they can be revealed by careful and rigorous analysis. In this spirit, the work of a structuralist anthropologist is much like that of a cryptographer decoding a secret message: he or she seeks to decipher the hidden structures that govern the way human societies function and develop.

Lévi-Strauss' structuralist approach has been influential and has led to new ways of thinking about human societies. However, like any theory, it has also been subject to criticism. Some people have questioned the idea that structures are so omnipresent and all-powerful, and have emphasised the role of individual agency and historical change. Others have criticised structuralism for its emphasis on duality and opposition, and for its sometimes too abstract and decontextualised approach to human cultures.

Marxist structuralism in the field of politics: Nicos Poulantzas (1936 - 1979)

Nicos Poulantzas was a Greek sociologist and political theorist who tried to reconcile structuralism and Marxism in his work. He is best known for his theory of the state, which has had a major influence on Western Marxism.

Poulantzas sought to integrate structuralism, in particular the ideas of Louis Althusser, into a Marxist analysis of society. Like Althusser, he emphasised the importance of overlying structures that shape and determine human actions and relations. However, he also insisted on the need for a materialist and class analysis of these structures.

In his book "Political Power and Social Classes", Poulantzas proposed a structural analysis of the capitalist state. According to him, the state is not simply an instrument of the ruling class, but an entity that has its own structure and its own role to play in maintaining the capitalist system.

Poulantzas also argued that the class struggle must be understood structurally. Classes are not only defined by their position in the economy, but also by their position in other social structures, such as the political system. This approach has allowed Poulantzas to develop a sophisticated analysis of how power and domination operate in capitalist societies.

Nicos Poulantzas is credited with making a significant contribution to Marxist theory, particularly with regard to the role of the state in capitalist societies. In his work he sought to understand how political and social structures interact with economic forces to maintain and reproduce systems of power and oppression. Poulantzas argued that the state is a relatively autonomous entity within the social structure, which has its own interests and plays an active role in maintaining the capitalist system. He rejected the idea that the state is simply an instrument of the ruling class, and argued instead that it is a "material condensation of a relation of forces between classes and class fractions".

In "Political Power and Social Classes" (1968), Poulantzas attempted to develop a Marxist theory of the state that takes into account its complexity and relative autonomy. He argued that the state, as a component of the social superstructure, is both the product and the producer of social relations of production. It plays an active role in the reproduction of the conditions of capitalist production. Poulantzas also wrote about fascisms and dictatorships, trying to understand their origins and development in the context of the capitalist political economy. He sought to develop an analysis that took into account both structural forces and the actions of individuals and groups.

Poulantzas was a leading figure in Western Marxism in the 1960s and 1970s, and his work had a significant influence on the development of Marxist theory. However, his ideas have also been criticised, particularly for their emphasis on structure at the expense of human agency.

Marxism was a major influence on the development of structuralism in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s. Marxist thought, with its emphasis on class structures and relations of production as the driving forces of history and society, was a perfect fit with the structuralist perspective, which sought to identify the underlying structures that organise and give meaning to social life. In this historical context, structuralism and Marxism were often used together to analyse social and political phenomena. For example, in the field of sociology, thinkers such as Louis Althusser have sought to integrate Marxist and structuralist ideas into a coherent theory of society. Decolonisation has also been a major topic of study for Marxist and structuralist thinkers. Struggles for independence in colonised countries have been interpreted through the prism of class relations and class struggle, while taking into account the specific cultural and political structures of each society. Nicos Poulantzas is an example of a thinker who openly claimed adherence to Marxism while using tools of structuralist analysis. His work on the role of the state in capitalist societies reflects this combination of influences.

Nicos Poulantzas has effectively proposed a structuralist analysis of capitalism and the state, focusing on class relations and institutional structures. According to him, the state is not a mere instrument of the ruling class, but rather a 'material condensation' of the power relations between the different classes. It is a field of struggle where various social, economic and political forces confront and negotiate each other. In this perspective, the state is not only an actor in the reproduction of class relations, but also plays an active role in their formation and transformation. It is both the product and the producer of social, economic and political relations. For Poulantzas, the capitalist state is not simply a reflection of the economic interests of the bourgeoisie, but is also an institution that contributes to the formation and reproduction of class domination. It structures social relations in a way that favours the ruling class and reproduces the conditions of capitalist domination. In this sense, Poulantzas' approach can be described as 'structuro-marxist', as it combines the analytical tools of Marxism and structuralism to analyse the state and capitalism. He was one of the main contributors to Marxist theory of the state, emphasising the role of the state as a site of class struggles and as an actor in the reproduction of class relations.

Nicos Poulantzas has indeed proposed an interesting vision of the crisis of the state. According to him, the crisis of the state is an intrinsic characteristic of the capitalist state, as it is always engaged in a class struggle and the management of the contradictions inherent in the capitalist system. Crisis is not an anomaly, but a normal and necessary aspect of the functioning of the capitalist state. According to Poulantzas, the state is not only a neutral regulator that arbitrates conflicts between different social classes. On the contrary, it plays an active role in the creation and management of these conflicts. It is a central actor in the reproduction of class relations and actively contributes to the formation of the class structure of society. From this perspective, the state is both a product of class conflicts and an actor who actively shapes these conflicts. It is both the theatre and the actor of class struggles. Therefore, the crisis of the state is not simply a consequence of class conflicts, but also a factor that contributes to their exacerbation. This view of the state has important implications for our understanding of political and social dynamics. It invites us to rethink the role of the state in capitalism and to acknowledge its active participation in the reproduction and transformation of class relations.

For Nicos Poulantzas, the state is the embodiment of the dominant forces in society and plays an active role in the reproduction of existing power relations. The state is not simply a neutral instrument, but an actor that actively shapes these power relations. The state, in its Marxist-structuralist conception, is a central actor in the construction and reproduction of class relations. It is not only a tool at the service of the ruling class, but an actor that actively contributes to the construction of the conditions that allow the ruling class to maintain its position. Poulantzas was also convinced that social and political change can only come from the struggle of the subaltern classes. For him, it is through popular mobilisation and class struggle that existing power structures can be challenged and transformed. This implies a vision of politics as a process of constant struggle, where popular forces must organise and mobilise to challenge existing power structures and work towards their transformation. It implies a vision of politics that emphasises collective action and popular mobilisation as the engines of social and political change.

Nicos Poulantzas was indeed aware of the complexities and contradictions inherent in structuralist theory. As a structuralist, he recognised that social structures carry considerable weight and tend to perpetuate themselves. However, as a Marxist, he also believed in the possibility of social and political change through collective action and class struggle. Poulantzas also recognised the potential of the state to exercise violence against the forces of change. He used the term 'preventive counter-revolution' to describe the measures taken by the state to prevent or thwart revolutionary movements. This idea reflects his understanding of the state not as a neutral actor, but as an entity that plays an active role in the defence and reproduction of existing power structures. It is true that these ideas may seem contradictory. On the one hand, Poulantzas recognises the weight of social structures and the tendency of the state to defend the existing order. On the other hand, he believes in the possibility of revolution and social change. However, these contradictions reflect the complexity of the social and political reality that Poulantzas sought to understand.

Annexes

References

- ↑ Differenz der demokritischen und epikureischen Naturphilosophie.