Functionalism and Systemism

La pensée sociale d'Émile Durkheim et Pierre Bourdieu ● Aux origines de la chute de la République de Weimar ● La pensée sociale de Max Weber et Vilfredo Pareto ● La notion de « concept » en sciences-sociales ● Histoire de la discipline de la science politique : théories et conceptions ● Marxisme et Structuralisme ● Fonctionnalisme et Systémisme ● Interactionnisme et Constructivisme ● Les théories de l’anthropologie politique ● Le débat des trois I : intérêts, institutions et idées ● La théorie du choix rationnel et l'analyse des intérêts en science politique ● Approche analytique des institutions en science politique ● L'étude des idées et idéologies dans la science politique ● Les théories de la guerre en science politique ● La Guerre : conceptions et évolutions ● La raison d’État ● État, souveraineté, mondialisation, gouvernance multiniveaux ● Les théories de la violence en science politique ● Welfare State et biopouvoir ● Analyse des régimes démocratiques et des processus de démocratisation ● Systèmes Électoraux : Mécanismes, Enjeux et Conséquences ● Le système de gouvernement des démocraties ● Morphologie des contestations ● L’action dans la théorie politique ● Introduction à la politique suisse ● Introduction au comportement politique ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : définition et cycle d'une politique publique ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : mise à l'agenda et formulation ● Analyse des Politiques Publiques : mise en œuvre et évaluation ● Introduction à la sous-discipline des relations internationales

Functionalism and systemism are two theoretical approaches in political science that attempt to understand the relationships, structures and processes within political systems.

- Functionalism: This concept focuses on the roles and functions that various elements of the political system play in maintaining the stability and equilibrium of the system as a whole. It examines how each part contributes to the stability of the overall system. In political science, functionalism can be used to analyse how different institutions (such as the legislature, the executive, the judiciary, etc.) contribute to the stability and functioning of the political system as a whole.

- Systemism: Systemism, or systems theory, is an approach that views political phenomena as part of a larger system. It focuses on the interactions between the different parts of the system and how these interactions influence the system as a whole. Systemism attempts to understand the political system as a whole rather than focusing solely on its individual parts.

Both theories can be used to understand power relationships, the interactions between different parts of a political system and how these contribute to stability or change in the political system.

Functionalism

Just as each organ in the human body has a specific function and contributes to the proper functioning of the organism as a whole, each institution or structure within a society has a specific function and contributes to the stability and well-being of society as a whole. Functionalism is based on the idea that society is a complex system whose different parts work together to promote solidarity and stability. In political science, this approach is used to analyse how different institutions or structures, such as government, the economy, education, the media, etc., contribute to the stability and functioning of society as a whole.

Society or politics is therefore interpreted as a living body. This anthropomorphic approach, which compares society to a living organism, helps us to understand how the different parts of society interact to create a functional whole. In this analogy, the different social and political institutions are compared to the organs of a body. For example, the government could be seen as the brain, providing directives and decisions for the rest of the body. The economy could be compared to the circulatory system, distributing resources (like blood and oxygen in a body) throughout society. Schools and universities could be seen as the nervous system, providing the education and information (analogous to nerve signals) that enable society to function. Just as the body needs all its organs to function properly, society needs all its institutions to maintain balance and stability. Moreover, just as the body's organs interact and depend on each other, social and political institutions are also interdependent and their interactions have an impact on the overall functioning of society.

Functionalism became a dominant theory in sociology and political science from the 1930s to the 1960s, particularly in the English-speaking world. Sociologists such as Talcott Parsons and Robert K. Merton played a crucial role in the development of functionalist theory. Talcott Parsons, in particular, is often regarded as one of the main contributors to functionalist theory. His theory of social action, which emphasises the interdependence of the parts of a social system and the role of norms and values in social stability, had a major influence on functionalism. Robert K. Merton introduced the notion of manifest and latent functions. Manifest functions are the expected and intended effects of social actions, while latent functions are the unintended and often unrecognised effects.

In the 1960s, functionalism was criticised for its emphasis on stability and social order, and for its failure to take account of social change and conflict. In response to these criticisms, new theories such as structural conflict and symbolic interactionism began to emerge. However, functionalism remains an important approach in sociology and political science, and its concepts continue to influence the way we think about societies and political systems.

From this perspective, each element of society, whether tangible or intangible, has a role to play in keeping the whole system in balance. The stability and smooth running of society are ensured by the interaction and interdependence of these various elements, each fulfilling its respective functions. For example, in a society, the production of goods and services is an essential function that enables the material needs of society's members to be met. Family and social structures ensure the reproduction and socialisation of new members, thus contributing to the continuity of society. Political and legal institutions protect and maintain order, thereby contributing to the stability and security of society. Similarly, every belief, value and social norm has a role to play. For example, religious beliefs can contribute to social cohesion by providing a framework of shared meaning and values. Social norms regulate the behaviour of individuals and promote cooperation and harmony within society.

According to functionalist theory, although every society must fulfil certain universal functions (such as the production of goods and services, reproduction and the protection of its members), the way in which these functions are fulfilled may vary from one society to another depending on its specific cultural and social institutions. This is where the concept of 'functional equivalents' comes in. Different cultural institutions or practices may fulfil the same function in different ways. For example, socialisation - the process by which individuals learn and integrate the norms and values of their society - can take place in different ways in different societies. In some societies, it may take place primarily through imitation, where individuals learn social norms by observing and imitating others. In other societies, it may be through fusion, where individuals are immersed in a social group and adopt its norms and values. In still other societies, socialisation can take place through transmission, where norms and values are explicitly taught and passed down from generation to generation. These different methods of socialisation are 'functional equivalents' in the sense that they all perform the same function - the socialisation of individuals - but in different ways. This illustrates the flexibility and variability of societies in the way they perform universal functions.

Functionalism originated in anthropology and has been influenced by several important thinkers:

- Bronisław Malinowski: A Polish-British anthropologist, Malinowski is often regarded as the founder of British social anthropology and one of the pioneers of functionalism. He introduced the idea that to understand a culture, we need to examine how its different parts work together to meet basic human needs. Malinowski also emphasised the importance of fieldwork and participant observation in the study of societies.

- Alfred Radcliffe-Brown: Another British anthropologist, Radcliffe-Brown, developed what he called "structural-functionalism". He saw society as an organic system, where each part has a specific function that contributes to the survival of the system as a whole. Radcliffe-Brown focused on the study of social relations as a structural system.

- Talcott Parsons: An American sociologist, Parsons developed a complex version of functionalism known as "social action theory". He saw society as an interconnected system of parts that work together to maintain a balance. Parsons emphasised the role of social norms and cultural values in maintaining social stability and argued that any social change must be gradual to preserve this balance.

- Robert K. Merton: Merton, also an American sociologist, made several important modifications to functionalist theory. Unlike Parsons, Merton did not believe that everything in society contributed to its stability and well-being. He introduced the concepts of manifest and latent functions, distinguishing between the expected and the unexpected or unrecognised effects of social actions. Merton also recognised the existence of dysfunctions, or the negative effects of social structures on society.

Bronislaw Malinovski (1884 - 1942): Anthropological functionalism or absolute functionalism

Bronisław Malinowski is one of the most important figures in twentieth-century anthropology. Born in Poland, Malinowski began his university studies at Kraków's Jagiellonian University, where he studied philosophy and physics. However, he soon became interested in anthropology and decided to continue his studies in this field. He then moved to London, where he began studying at the London School of Economics (LSE). At the LSE, he worked under the anthropologist C.G. Seligman and obtained his doctorate in 1916. His thesis, based on his fieldwork in Melanesia, laid the foundations for his functionalist approach to anthropology. He embarked on extensive fieldwork in Melanesia, a region of the South Pacific that includes many islands, including Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia and others. His fieldwork laid the foundations for the method of participant observation, which remains a central method in anthropology today. This approach involves living in the community being studied for an extended period of time, learning the local language and participating as much as possible in the daily life of the community.

His most famous book, "The Argonauts of the Western Pacific", is a detailed study of the Kula, a complex system of trade between the various islands of Melanesia. In this work, Malinowski not only described the Kula system in detail, but also sought to understand how it functioned in the wider context of Melanesian society, including its role in politics, religion and social life. Malinowski's contribution to functionalist theory rests on his idea that every aspect of a culture - including its rituals, myths, economic and social systems - has a specific function that contributes to the satisfaction of the basic needs of the people in that culture. This approach had a lasting influence on anthropology and also contributed to the emergence of functionalist theory in sociology and political science.

Bronisław Malinowski is famous for spending several years on the Trobriand Islands (now known as the Kiriwina Islands in Papua New Guinea) from 1915 to 1918. During this period, he lived among the local population and took part in their daily activities, a method of field study known as participant observation. One of Malinowski's most important observations during his time on the Trobriand Islands was the trading system known as Kula. This complex system of trade between different islands involved the exchange of red shell necklaces and white shell bracelets, which were traded in opposite directions around a circle of islands. Malinowski argued that the Kula system was not only a form of economic exchange, but also a means for individuals to establish and maintain social and political relationships.

Malinowski's approach was revolutionary at the time and greatly influenced the development of anthropology. He showed that a complete and accurate understanding of a culture can only be obtained by living within that culture and participating in its daily activities. This provided an insider's perspective on how the different parts of the culture - economy, politics, religion, etc. - work together to meet the needs of the population.

The Kula system, observed by Bronisław Malinowski in the Trobriand Islands, is a system of ritual exchange in which precious objects are given without expectation of immediate payment, but with the implicit obligation that they will eventually be returned. There are two main types of object exchanged in the Kula: necklaces of red shells, called soulava, which circulate clockwise around a circle of trading partners, and bracelets of white shells, called mwali, which circulate anti-clockwise. These objects have no utilitarian value in themselves, but are precious because of their history and symbolic significance. Individuals taking part in the Kula sometimes travel long distances to exchange these objects. When an object is received, it is kept for a certain period of time and then given to another trading partner in a subsequent exchange. By participating in the Kula, individuals establish and strengthen social and political ties, acquire prestige and navigate complex relationships of reciprocity and obligation. Malinowski's work on the Kula has been highly influential and has helped to shape our understanding of economics, politics and culture in non-Western societies. He also played a key role in the development of functionalist theory in anthropology, which sees the different parts of a culture as interconnected and working together to meet the needs of society.

The Kula is a ritual system of exchange that does not correspond to traditional Western economic models. The objects exchanged in the Kula - soulava shell necklaces and mwali shell bracelets - have no intrinsic value as material goods, but acquire great symbolic and social importance in the context of the Kula. What is particularly interesting about the Kula is that it is not a one-off exchange, but a continuous system of exchange. An object received under the Kula is not kept permanently, but must be given to another trading partner in a subsequent exchange. In this way, Kula objects are constantly on the move, circulating from one individual to another and from one island to another. Moreover, Kula exchanges are accompanied by complex rituals and ceremonies, and participation in the Kula confers prestige and social status. The Kula is therefore much more than a simple system of economic exchange: it is a complex social and cultural phenomenon that strengthens social ties, establishes reciprocal relationships and structures the political and social life of the Trobriand Islands. In studying the Kula, Malinowski demonstrated that to truly understand a social or cultural phenomenon, it is necessary to study it in context and understand how it fits into the overall functioning of society. This is one of the fundamental principles of anthropology and functionalist theory.

The Kula is a system of exchange which, although not involving financial elements in the traditional sense of the term, is of crucial importance for social cohesion and for maintaining links between the different communities on the islands. The objects exchanged in the Kula are symbolic goods that serve to strengthen relationships between people and maintain a certain form of stability and continuity in society. The Kula is also a highly ritualised and regulated process. There are specific rules about who can participate in the Kula, what objects can be exchanged and how they should be exchanged. What's more, Kula exchanges are often accompanied by magical and religious rituals, further underlining their social and cultural significance.

Malinowski's approach of analysing cultural practices in terms of their functions within society is a key feature of functionalist theory. In the case of the Kula, Malinowski showed that what may appear to be a simple system for exchanging goods is in fact a crucial element in the social and political structure of the Trobriand Islands.

Bronisław Malinowski's functionalist view sees cultural practices and institutions not as isolated elements, but as integral parts of a wider social system that functions to meet the needs of society. In the case of the Kula, the function of this system of exchange is not primarily economic, but rather social and political. The Kula serves to strengthen social ties between individuals and communities, to establish and maintain reciprocal relationships, and to structure social and political relations. By forcing people to meet and exchange ideas on a regular basis, the Kula fosters peace and cooperation between the different communities of the Trobriand Islands.

This functionalist view has important implications for the way we understand and analyse political and social systems. It suggests that to fully understand a cultural institution or practice, we need to examine its function in the context of society as a whole. This approach can help us to understand how different institutions and practices contribute to social cohesion, political stability, and other aspects of the functioning of society.

Alfred Radcliffe-Brown: 1881 - 1955

Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, a British anthropologist, played a fundamental role in the development of structuralism and functionalism in the field of anthropology. He is best known for his studies of Aboriginal societies in Australia.

Radcliffe-Brown proposed the idea that societies can be understood as structured systems of social interaction, where each part of the society has a specific function that contributes to the stability and survival of the whole. He compared society to a biological organism, where each organ has a specific function that contributes to the well-being of the whole body. In his book Structure and Function in Primitive Society, Radcliffe-Brown explored these ideas in detail. He argued that primitive societies, such as those of the Australian Aborigines, have complex social, political and spatial structures that are largely invisible to the untrained eye, but can be revealed by careful analysis. Radcliffe-Brown also emphasised the importance of rituals and myths in these societies, which he saw as key tools for maintaining social order and ensuring group cohesion. For him, these cultural elements are not mere superstitions, but essential functional elements of society.

Radcliffe-Brown's contribution to anthropology and functionalist theory has been hugely influential. His work laid the foundations for many subsequent studies of social structure and political systems in a variety of cultural contexts.

Radcliffe-Brown merged the ideas of structuralism and functionalism to create structural-functional theory.

From this perspective, a society is seen as a system of interconnected structures, each with a specific function that contributes to the stability and integrity of the system as a whole. These structures are the result of social practices and interactions, not of biological or arbitrary factors. They are the product of human activity, but they exist outside individuals and influence them. Structuralism stresses the need to examine societies as a whole and to understand how the different parts fit together to form a coherent whole. Functionalism, on the other hand, focuses on analysing the specific functions that each part of a society fulfils in the context of the wider social system.

Structural-functionalism combines these two approaches by focusing both on how social structures are created by specific social functions and on how these structures contribute to the stability and cohesion of society as a whole. This approach has been widely used in anthropology and sociology to analyse a wide variety of societies and cultures.

In structural-functionalism, the structures of society are seen not simply as rigid, immutable entities, but as dynamic, interactive elements that play an active role in the organisation of social life. These structures can take many forms, such as social institutions, cultural norms, belief systems, rituals and even forms of communication. Each structure fulfils a specific function that contributes to the stability and order of society. For example, an institution such as marriage may have the function of regulating sexual relations, providing a framework for the upbringing of children, and defining the roles and responsibilities of men and women in society. These structures also function as regulatory mechanisms that help maintain social balance and prevent chaos or disorder. They promote cooperation and harmony between individuals and groups by establishing rules and common standards of behaviour. In short, in the structural-functionalist perspective, the structures of society are seen as essential elements that enable people to live together in an orderly and functional way.

Structural-functionalism recognises that societies are not static, but dynamic and capable of adapting and evolving in response to various factors. This adaptability can manifest itself at several levels:

- Ecological: Societies can adapt to their physical and ecological environment by changing their livelihoods, technologies or environmental practices in response to changes in their environment.

- Institutional: Social, political and economic institutions can change and adapt in response to internal or external factors. For example, a society may reform its political institutions in response to social pressure for greater democracy or social justice.

- Cultural: A society's values, norms and beliefs can also evolve and adapt over time. For example, a society may change its attitudes towards certain behaviours or social groups in response to wider cultural or ideological changes.

These different levels of adaptability can interact and reinforce each other, leading to profound transformations in the structure and function of society. However, even in the context of these changes, structural-functionalism suggests that societies will maintain a certain coherence and stability, because the new structures and functions that emerge will serve to maintain social order and cohesion.

With the concept of social system in the structuralo-functionalist perspective. Society is seen as a complex organism made up of interdependent elements - individuals, groups, institutions - which are all connected by social relationships. None of these elements exists in isolation; they are all part of a larger whole and contribute to its functionality and stability. In this sense, the 'social system' is not simply a collection of individuals, but an organised entity with its own structures and functions. These structures are not only shaped by the interaction of individuals, but also influence the behaviour and attitudes of individuals. They create a framework of norms, values and rules that guide the behaviour of individuals and help to maintain social order and cohesion. In this sense, collective values play a central role in the social system. They provide a common basis of understanding and identification that binds individuals together and facilitates cooperation and social harmony. These values can be incorporated into the institutions and cultural practices of a society, helping to shape the way individuals interact and behave with each other.AA

he notion of a social system is central to sociology and political science, particularly from structuralist and functionalist perspectives. A social system is an organised set of social interactions structured around shared norms, values and institutions. It is a framework that organises and regulates the behaviour of individuals and groups within society. In a social system, institutions play a crucial role. Institutions are durable structures that establish rules and procedures for social interaction. They include formal organisations such as government, schools and businesses, as well as informal cultural norms and values. Institutions help to structure social behaviour, create predictability and order, and facilitate cooperation and coordination between individuals and groups. By adhering to the norms and values of a social system, individuals contribute to the stability and continuity of that system. However, social systems are also dynamic and can change and evolve in response to internal and external factors. Sociology, as a discipline, is concerned with the study of these social systems - how they are structured, how they function, and how they change and develop over time.

A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, in his structural-functionalist approach, emphasised the concept of adaptability, the capacity of a social system to adjust and change in response to internal and external constraints. According to Radcliffe-Brown, society is an integrated system of institutions, each with a specific function to fulfil in order to maintain the whole. This idea, borrowed from biology, postulates that a society, like an organism, is a system of interdependent elements that work together for the survival and equilibrium of the overall system. Each institution or social structure has a function to fulfil in this system - it must contribute to the stability and cohesion of society. Regarding the link between structure and function, Radcliffe-Brown saw structure as an arrangement of interdependent parts, each with a specific function to perform. He argued that the function of an institution or social practice should be understood in terms of its role in maintaining the overall social structure. As for adaptability, Radcliffe-Brown argued that societies have the capacity to adapt and modify themselves in response to environmental and social change. This may involve changes to social institutions, norms, values, etc., in order to maintain the balance and stability of the social system as a whole. This is how Radcliffe-Brown conceived the dynamic between structure, function and adaptability in a society.

Talcott Parsons: 1902 - 1979

Talcott Parsons is one of the most influential theorists in twentieth-century sociology and social theory. Talcott Parsons began his studies in biology at Amherst College before turning to sociology and economics. He then studied at the London School of Economics, where he was influenced by the work of a number of leading figures in sociology and economics, including Harold Laski, R.H. Tawney, Bronislaw Malinowski and Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse. He subsequently completed a doctorate in sociology and economics at the University of Heidelberg in Germany.

Parsons made a significant contribution to functionalist theory, focusing on how different parts of society contribute to its integration and stability. His work greatly influenced the development of structural functionalism, which views society as a system of interdependent interactions.

In Politics and Social Structure, Parsons explored how social and political structure affects individual and collective actions. He suggested that actions are governed by shared norms and values within society, which are in turn influenced by social and political structure. In 'Social Systems and the Evolution of Action Theory', Parsons developed his theory of action, which centres on the idea that human action is directed and regulated by cultural norms and values. He argued that individual actions are linked to wider social systems and that these systems evolve and change over time. Finally, in 'Action Theory and the Human Condition', Parsons further developed his theory of action, focusing on how actions are influenced by human conditions, such as physiological and psychological needs, cognitive abilities and social relationships.

Talcott Parsons is one of the most important sociologists of the 20th century, not least because of his systemic approach to social action. For him, action is not just an individual act, but is embedded in a system of action. This system of action is an interdependent set of behaviours aimed at achieving a certain objective. We therefore need to understand not only individual action, but also how that action fits into a wider set of social relations and institutions. In this context, government, public policy and institutions are not just the result of the actions of isolated individuals, but form part of a complex system of social interactions. This emphasises the importance of social structure in determining the behaviour of individuals, and how individual actions help to reproduce or transform that structure. For example, government policy can be understood as the product of a system of action comprising politicians, bureaucrats, interest groups and citizens, each acting according to their own motivations, but all contributing to the implementation of policy within the framework of specific social structures. This systemic approach to social action has had a major influence on sociology and political science, particularly in the analysis of institutions, public policy and power.

In Talcott Parsons' thinking, a system of action is a set of interdependent units of action. Each unit of action is guided by norms and values that direct its behaviour towards specific objectives. These units of action may be individuals, but also groups, organisations or entire societies. In this system, the actions of the various units are linked together to form a coherent whole. In this way, individual choices are influenced by the system of actions as a whole, and in turn help to shape that system. For example, in an organisation such as a company, the actions of individual employees are coordinated to achieve the company's objectives. Each employee acts according to their specific role in the organisation, but their actions also contribute to the achievement of the company's overall objectives.

What is important in this perspective is that individual actions are not simply determined by the personal preferences of individuals, but are also influenced by the norms, values and objectives of the action system as a whole. In this way, individual choices are both influenced by and influence the overall system of action.

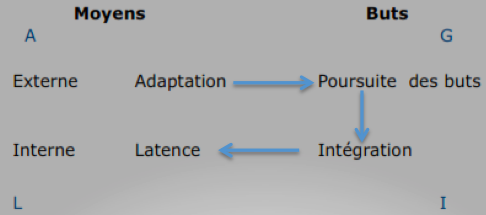

Talcott Parsons conceptualised what he called "action system theory" (or the "AGIL scheme" - Adaptation, Goal attainment, Integration, Latency) to explain how societies (or any social system) attempt to maintain social balance and order. Each of the four functions in this diagram is essential for the survival of a social system. They all work together, and if one of them fails, the system may be in danger.

- Adaptation: This concerns the ability of a social system to gather and use resources from its environment in order to survive and prosper. It is fundamentally the system's relationship with its environment, and how it adapts to it.

- Goal attainment: This refers to the system's ability to define and pursue goals. In a society, this could be seen as the role of government, which sets policy goals and implements policies to achieve them.

- Integration: This function relates to the management of relationships between different parts of the social system to maintain order and avoid conflict. This is the aspect of social cohesion, how the different parts of a system work together to maintain unity.

- Latency: This function concerns the maintenance and renewal of the motivations, values and norms that underpin the system. It is the cultural 'glue' that binds people together and keeps the system running.

These four functions interact with each other and are all necessary for the survival of a social system.

In reality, perfect respect for these four functions is rarely achieved. Social systems are complex and dynamic, and are subject to many internal and external pressures that can disrupt their functioning.

- Adaptation: Social systems can fail to adapt appropriately to changes in their environment. For example, a company may not be able to adapt quickly to a new technology, which could lead to its bankruptcy. Similarly, a company may find it difficult to adapt to rapid changes, such as those brought about by globalisation or climate change.

- Pursuit of goals: Social systems can also fail to define and achieve their goals. For example, a government may fail to achieve its objectives in terms of poverty reduction, unemployment, education, health, etc.

- Integration: Tensions and conflicts can arise within a social system, threatening its integrity. For example, social, ethnic, religious or political divisions can threaten the stability of a society.

- Latency: Finally, social systems may experience difficulties in maintaining and renewing the values, norms and motivations that sustain their existence. For example, a crisis of values can occur when traditional norms are challenged or when people feel disconnected from the dominant values of society.

These problems are often interconnected and can reinforce each other, creating significant challenges for the stability and sustainability of social systems. Therefore, understanding these functions and how they can be supported and strengthened is crucial to the management and resolution of social problems.

Parsons' functional paradigm of the action system is circular and dynamic. Each function, or phase, of the cycle - Adaptation, Goal Pursuit, Integration, Latency - is not only the consequence of the previous phase, but also the condition for the next.

In other words, each function must be performed not only to meet the system's immediate needs, but also to prepare the system to perform the next function. For example, Adaptation (the ability of the system to use the resources of the environment to meet its needs) is necessary not only for the immediate survival of the system, but also to enable it to define and pursue its Goals. Similarly, the achievement of Goals is a prerequisite for Integration (the co-ordination and cohesion of the system), which in turn prepares the system for the Latency phase (the generation and conservation of energy or motivation for action).

In this way, the action system is always in motion, moving from one phase to another in a continuous loop. This dynamic cycle model reflects the complexity and interdependence of social processes in action systems.

Robert King Merton (1910 - 2003): mid-range functionalism

Robert King Merton was a renowned and influential American sociologist. Born on 4 July 1910 and died on 23 February 2003, Merton is best known for developing fundamental concepts in sociology, such as the theory of manifest and latent functions, anomie, self-fulfilling prophecy, the role model and the Matthew effect. Merton also made a significant contribution to the sociology of science with his analysis of the phenomenon of 'priority' in scientific discovery. He also studied the impact of certain social structures on the conduct of science. His work on manifest and latent functions has been particularly influential. Manifest functions are the intended and recognised consequences of a social phenomenon or action, while latent functions are the unintended and often unrecognised consequences. For example, in the case of education, a manifest function would be the acquisition of knowledge and skills, while a latent function might be the socialisation of individuals into certain societal norms and values. His work has profoundly influenced sociology and continues to be widely cited and used in contemporary sociological research.

Robert Merton brought a more nuanced perspective to functionalist theory, recognising that individuals play an active role in society and that social dysfunction is an inherent reality of any social organisation.

- The role of individuals: Merton emphasised that, although social structures exert a strong influence on the behaviour of individuals, the latter are not simply passive in the face of these structures. On the contrary, they are capable of interpreting their social environment and acting in creative and often unpredictable ways. In other words, Merton recognised that individuals are both influenced by the social system and capable of influencing it in return.

- Anomie and social dysfunction: Merton also pointed out that not all parts of a social system always work harmoniously together. He introduced the concept of anomie to describe a state of confusion, disorder or lack of clear rules, which can occur when social structures change rapidly or when cultural expectations conflict. In addition, Merton pointed out that social dysfunction, such as deviance and crime, is often a response to anomie.

Robert Merton was influenced by Émile Durkheim, one of the founding fathers of modern sociology. Durkheim developed functionalist theory, which focuses on how the different elements of a society work together to maintain order and stability. Durkheim's influence on Merton is particularly evident in the concepts of anomie and social dysfunction. Durkheim introduced the concept of anomie to describe a state of social disintegration where individuals no longer feel guided by shared norms and values. He argued that anomie results from a lack of social regulation and can lead to problems such as suicide and crime. Merton took this concept and developed it by analysing the causes and consequences of anomie in the context of American society. He also integrated Durkheim's ideas on social functions and dysfunctions into his own functionalist theory. In short, Merton helped to extend and deepen functionalist theory by building on Durkheim's work and adapting it to new social contexts and problems. Merton's contributions to functionalist theory made the approach more dynamic and better able to account for the complexity of social life.

In Merton's theory of anomie, anomie is seen as a state of disequilibrium caused by the mismatch between cultural goals and the institutionalised means of achieving them. In other words, when a society imposes expectations or aspirations on its members that they cannot achieve by legitimate means, this can lead to anomie, or a sense of alienation and disorientation. Anomie, from this perspective, can manifest itself in a number of ways, for example through deviant behaviour, such as crime or rebellion against established social norms. It can also lead to social disorganisation, conflict and tension within society. It is important to emphasise that for Merton, anomie is not simply an absence of norms, but rather a breakdown or inconsistency in the normative system of society. This may result from rapid and profound changes in society, or from the inability of social institutions to adapt or respond to new conditions or demands. In all cases, anomie represents a form of social dysfunction, where the normal structures and processes of society are disrupted or undermined.

The concept of anomie reflects a situation in which the social norms that govern the behaviour of individuals are weakened or confused. This can occur when society is undergoing rapid and profound change, or when there is a significant mismatch between the cultural aspirations of a society and the legitimate means available to achieve those aspirations. In this context, anomie can be seen as a kind of 'grey zone' between an old social order and a new order that has not yet been clearly defined or accepted. It is a potentially problematic period of transition, during which individuals may feel lost, disorientated or uncertain about how to behave. Anomie is described not only as a social structure that no longer functions, but also as individuals who are waiting for a lost meaning and who, in the expectation of this lost meaning, may redefine specific behaviours, particularly violent or deviant behaviours. Deviance is behaviour that no longer corresponds to the behaviour and aspirations of society. Deviance occurs when there is a disproportion between the cultural flows considered valid and the legitimate means to which individuals can have access to achieve these goals. It should also be noted that Merton uses the concept of anomie to explain deviance and crime in society. According to him, when individuals cannot achieve their goals by legitimate means (for example, because of poverty or discrimination), they may be tempted to resort to illegitimate means, which can lead to deviant or criminal behaviour.

Selon Merton, la déviance est un symptôme d'un dysfonctionnement ou d'une désorganisation au sein d'un système social. Quand il y a un écart entre les objectifs culturellement valorisés dans une société et les moyens socialement acceptés pour atteindre ces objectifs, cela crée une tension ou une pression qui peut conduire à la déviance. Dans le cadre de la mafia, si une société valorise la richesse et le succès économique, mais que les moyens légitimes pour atteindre ces objectifs (par exemple, l'éducation, le travail acharné, l'entrepreneuriat) sont inaccessibles à certains groupes de personnes (en raison de la pauvreté, de la discrimination, etc.), alors ces personnes peuvent être tentées de recourir à des moyens illégitimes (comme le crime organisé) pour atteindre ces objectifs. En ce sens, la déviance peut être vue non seulement comme un symptôme d'un dysfonctionnement social, mais aussi comme une réponse créative ou adaptative à ce dysfonctionnement. Cependant, cette réponse peut en elle-même créer de nouveaux problèmes et défis, comme la criminalité, la violence et l'instabilité sociale.

In "Contemporary Social Problems: An Introduction to the Sociology of Deviant Behavior and Social Disorganization", Merton and Nisbet analyse how social and cultural structures can produce both compliant and deviant behaviour. Merton developed a theory called 'structural deviance theory', which analyses how the social and cultural structure of a society can lead to deviance. According to this theory, when the social structure of a society establishes cultural goals, but does not provide all its members with the legitimate means to achieve these goals, some individuals may resort to deviance in order to achieve these goals. In addition, Merton also introduced the concept of 'social disorganisation' to describe a situation where social norms and rules of behaviour are weak or non-existent, which can lead to a high level of deviant behaviour. Merton's theory has had a considerable influence on the sociology of deviance and remains a major reference in the field.

In their analysis of social disorganisation, Merton and Nisbet identified several key factors that can contribute to the disorganisation of a social system:

- Institutional conflicts: These occur when the institutions of a society come into conflict with each other. For example, in a society where economic values take precedence over family values, an individual may be torn between the need to work long hours to achieve economic success and the desire to spend time with his or her family. These types of conflicts can create stress, confusion and disorganisation within society.

- Social mobility: Excessive or insufficient social mobility can also contribute to social disorganisation. For example, in a society where social mobility is very low, individuals can feel trapped and frustrated, which can lead to deviance and social disorganisation. Conversely, in a society where social mobility is very high, individuals may feel disconnected from their community and roots, which can also lead to social disorganisation.

- Anomie: Anomie, a concept Merton borrowed from Durkheim, refers to a situation in which social norms are weak or confused, which can lead to deviance and social disorganisation. In an anomic society, individuals can feel lost and disorientated, not knowing how to behave or what goals they should be pursuing.

Functionalism is an approach that examines the functions of social phenomena and how they contribute to the stability and continuity of society as a whole. Functionalism focuses on the interdependence of different parts of society and how they fit together to form a coherent whole. The Kula is an excellent example of this kind of phenomenon. The Kula is a complex system of ritual exchanges practised by the inhabitants of the Trobriand Islands in Papua New Guinea. Although these exchanges involve objects of value, their true function, according to anthropologists such as Bronislaw Malinowski, is not economic but social. The Kula system creates links between different communities, fosters cooperation, reinforces social status and prevents conflict. In this way, it contributes to the stability and order of society as a whole. So while individual exchanges may seem irrational or inefficient from an economic point of view, they are in fact functional for society as a system. It is this aspect of functionalism - the idea that social institutions and practices can have important social functions, even if they are not immediately obvious - that has been particularly influential in sociology and anthropology.

From a functionalist perspective, individuals are seen as integral parts of a larger social system. Their behaviour, values and norms are expected to support the overall functioning and stability of that system. This is often referred to as social integration - the process by which individuals are led to accept and adhere to the norms and values of the social system in which they live. However, there can be variations in the degree to which individuals integrate. Some may adhere closely to the dominant norms and values, while others may deviate from them. These deviations from the norm are often referred to as 'deviations'. Deviance is not necessarily negative or destructive to the social system. Sometimes it can be a driving force for change and evolution. For example, deviant behaviour may challenge existing norms and values, leading to their re-evaluation and change. In other cases, deviance can reinforce norms and values by providing an example of what not to do. However, excessive or destructive deviance can threaten the stability of the social system. This is where social control mechanisms come in, designed to discourage deviance and encourage conformity to the norms and values of the system. These mechanisms can take many forms, ranging from formal sanctions (such as legal punishment) to informal sanctions (such as social disapproval). In short, from a functionalist perspective, individuals are both products and producers of the social system. Their behaviour can support or challenge the system, and the system, in turn, seeks to regulate their behaviour in order to maintain its own equilibrium and stability.

La théorie systémique

La théorie systémique, est une façon d'aborder l'action sociale ou humaine qui tient compte de différents niveaux ou systèmes d'interaction. Ces systèmes peuvent être compris comme suit :

- Système biologique : Il s'agit du niveau le plus élémentaire de l'action humaine, qui comprend les besoins et motivations physiques de base d'un individu, tels que la faim, la soif, le sommeil et l'évitement de la douleur. Ce système est généralement influencé par la génétique et la biologie de l'individu.

- Système de la personnalité : Ce système se réfère à la structure psychologique de l'individu, y compris ses traits de personnalité, ses attitudes, ses valeurs et ses motivations plus complexes. Ce système est influencé par les expériences individuelles de la personne, y compris son apprentissage, son socialisation et ses expériences de vie.

- Système social : Ce système englobe les interactions et relations de l'individu avec d'autres personnes et avec les institutions sociales. Il comprend les structures sociales comme la famille, l'école, le lieu de travail, les communautés et la société dans son ensemble.

- Système culturel : Ce système comprend l'ensemble des valeurs, normes, croyances et symboles qui sont partagés par un groupe ou une société. La culture influence la façon dont les individus perçoivent et interprètent le monde autour d'eux, et elle fournit un cadre pour comprendre et donner un sens à leur comportement.

Dans cette perspective, l'action humaine est vue comme le produit d'une interaction complexe entre ces différents systèmes. Chaque système influence et est influencé par les autres, créant un réseau dynamique et interdépendant d'influences qui façonnent le comportement humain.

Quelle est la différence entre une approche de politique traditionnelle et une approche systémique ?

L'approche systémique de l'analyse politique diffère de l'approche traditionnelle de plusieurs façons importantes.

Dans l'approche traditionnelle, l'accent est souvent mis sur les acteurs individuels et leurs décisions. Les politiciens, les partis politiques, les bureaucrates, les électeurs, les groupes d'intérêt, etc., sont analysés comme des entités distinctes qui prennent des décisions en fonction de leurs intérêts, de leurs idéologies ou de leurs motivations personnelles.

En revanche, l'approche systémique met l'accent sur les interactions entre ces acteurs et la façon dont ils sont influencés par les structures plus larges du système politique. Les acteurs sont vus non pas comme des entités isolées, mais comme des parties d'un système interconnecté qui agissent en fonction des contraintes et des opportunités offertes par le système. Dans cette perspective, les ressources, la puissance et les avantages sociaux ne sont pas simplement possédés par des acteurs individuels, mais sont distribués et négociés à travers le système. Les acteurs acquièrent leur puissance et leurs avantages non seulement grâce à leurs propres actions, mais aussi grâce à leurs relations avec d'autres acteurs et à leur position dans le système. En outre, l'approche systémique tient compte des conflits et des compétitions entre les acteurs. Au lieu de supposer que tous les acteurs partagent les mêmes intérêts ou objectifs, cette approche reconnaît que les acteurs peuvent avoir des intérêts divergents et peuvent entrer en conflit les uns avec les autres pour obtenir des ressources ou du pouvoir.

En somme, l'analyse systémique offre une perspective plus holistique et dynamique de la politique, qui met l'accent sur les interconnexions, les relations de pouvoir et les processus de changement.

Dans l'analyse systémique, le système est considéré comme un tout cohérent, même si ce dernier est composé de nombreux sous-systèmes et acteurs individuels. Chaque élément du système est considéré en relation avec les autres et non de manière isolée. L'accent est mis sur la cohérence du système dans son ensemble, plutôt que sur les actions ou les caractéristiques de ses composants individuels. La notion de rétroaction est également essentielle dans l'analyse systémique. Les systèmes sont vus comme des entités dynamiques qui sont constamment en train de changer et de s'ajuster en réponse à diverses forces internes et externes. Ce processus d'ajustement implique une forme de rétroaction, où les résultats des actions antérieures influencent les actions futures.

Dans ce contexte, la prise de décision n'est pas perçue comme un processus linéaire, mais plutôt comme un processus cyclique et récursif. Les décisions sont prises, mises en œuvre, évaluées, puis révisées en fonction de leur efficacité. Cela peut conduire à des changements dans les objectifs, les stratégies, les politiques, etc. C'est ce qu'on appelle souvent une "causalité non linéaire", où les effets ne sont pas simplement proportionnels aux causes, mais peuvent être influencés par une variété de facteurs interdépendants. Cela rend l'analyse systémique particulièrement utile pour étudier des situations complexes et dynamiques où il y a de nombreuses variables en jeu.

David Easton (1917 - 2014) : la théorie systémique en sciences politiques

David Easton est un politologue canadien reconnu pour sa contribution à la théorie politique et à la méthodologie de la recherche en sciences politiques. Né en 1917 et décédé en 2014, Easton a été l'un des pionniers de l'approche systémique en sciences politiques.

Dans son œuvre "A Framework for Political Analysis" (1965), Easton a proposé un modèle de système politique qui est devenu fondamental dans la théorie politique. Son approche systémique a défini le système politique comme une entité complexe qui reçoit des intrants (inputs) de la société environnante, les transforme à travers un "processus de conversion politique" et produit des extrants (outputs) sous forme de politiques publiques. Selon Easton, les intrants dans le système politique incluent les demandes et les soutiens de la part des citoyens et d'autres acteurs de la société. Ces intrants sont transformés par le système politique à travers une série de processus, notamment la formulation des politiques, la prise de décision, la mise en œuvre des politiques et l'évaluation des politiques. Les extrants du système politique sont les politiques publiques et les actions qui en résultent. Ces extrants ont un impact sur la société et peuvent à leur tour générer de nouvelles demandes et soutiens, créant ainsi une boucle de rétroaction. La théorie des systèmes politiques d'Easton a été largement influente dans le domaine des sciences politiques et a fourni un cadre conceptuel pour l'étude de la politique comme un système complexe d'interactions entre divers acteurs et processus.

David Easton est connu pour avoir appliqué la théorie des systèmes à l'étude de la politique. Dans cette perspective, il a conceptualisé le système politique comme un processus d'entrées (inputs), de conversions et de sorties (outputs). Les entrées comprennent les demandes et les soutiens. Les demandes proviennent des individus, des groupes et des institutions de la société qui veulent que le système politique agisse d'une certaine manière. Les soutiens sont les ressources que les individus, les groupes et les institutions sont prêts à donner au système politique pour qu'il fonctionne. Les conversions représentent le processus politique lui-même - comment le système politique traite les demandes et les soutiens, prend des décisions et crée des politiques. Les sorties sont les décisions et actions du système politique qui affectent la société. Selon Easton, il y a également des boucles de rétroaction dans ce système. Les sorties du système politique affectent les entrées, car les actions du système politique peuvent modifier les demandes et les soutiens. Cela crée un cycle continu d'entrées, de conversions et de sorties. Cette approche systémique a permis à Easton de considérer la politique comme un ensemble interconnecté d'activités plutôt que comme une série d'événements isolés. Cela a permis une analyse plus complexe et nuancée du fonctionnement du politique.

Dans son ouvrage The Political System publié en 1953 David Easton a adopté une perspective universelle dans son approche de la politique. Selon lui, tous les systèmes politiques, qu'ils soient démocratiques, autoritaires, totalitaires ou autres, partagent des caractéristiques communes qui permettent de les étudier de manière comparative. L'approche d'Easton se distingue de celle de l'anthropologie, qui met souvent l'accent sur la diversité et la singularité des cultures et des systèmes politiques. L'anthropologie tend à adopter une perspective relativiste, affirmant qu'il n'y a pas de normes universelles par lesquelles évaluer les cultures et les systèmes politiques, mais que chaque culture ou système doit être compris dans son propre contexte. Cependant, Easton considérait que son approche systémique offrait une base pour l'analyse comparative. Il soutenait que, bien que les systèmes politiques puissent différer en surface, ils partagent tous des processus fondamentaux similaires d'entrées, de conversions et de sorties. En se concentrant sur ces processus communs, Easton croyait qu'il était possible de tirer des conclusions générales sur le fonctionnement de la politique. Cela ne signifie pas que l'approche d'Easton négligeait les différences entre les systèmes politiques. Au contraire, il reconnaissait que la manière dont ces processus se déroulent peut varier considérablement d'un système à l'autre. Cependant, il estimait que ces variations pouvaient être comprises à travers le prisme de sa théorie systémique.

David Easton a proposé une approche systémique pour étudier la politique, suggérant que les phénomènes politiques pourraient être mieux compris si on les analysait comme des systèmes interconnectés. Il croyait que la société contemporaine, bien que complexe, pouvait être organisée et comprise en termes de systèmes. Selon Easton, un système politique comprend un ensemble d'interactions qui convertissent les entrées (demandes et soutiens de la part des citoyens) en sorties (décisions et actions politiques). Ces sorties ont ensuite des effets sur la société, qui produisent de nouvelles entrées, créant ainsi un cycle continu. Easton a également souligné l'importance de l'environnement d'un système politique, qui comprend d'autres systèmes sociaux, tels que l'économie, la culture, le système juridique, etc. Il a reconnu que ces systèmes peuvent influencer et être influencés par le système politique. Ainsi, l'approche d'Easton a cherché à fournir une vision globale de la politique, qui prend en compte à la fois les processus internes des systèmes politiques et leurs interactions avec d'autres systèmes sociaux. Cette perspective systémique a été influente dans le domaine des sciences politiques et continue d'être utilisée par de nombreux chercheurs aujourd'hui.

David Easton a souligné l'importance de ces fonctions dans l'élaboration d'une théorie politique. Expliquons un peu plus en détail :

- Proposer des critères pour identifier les variables à analyser : cela signifie déterminer quels éléments ou caractéristiques d'un système politique sont les plus importants à étudier. Cela pourrait inclure des choses comme les structures de gouvernance, les processus décisionnels, les politiques publiques, etc.

- Établir des relations entre ces variables : une fois que les variables pertinentes ont été identifiées, la prochaine étape est de comprendre comment elles sont liées les unes aux autres. Par exemple, comment les structures de gouvernance influencent-elles les processus décisionnels ? Comment les processus décisionnels influencent-ils les politiques publiques ?

- Expliquer ces relations : après avoir identifié les relations entre les variables, la prochaine étape est d'expliquer pourquoi ces relations existent. Quels mécanismes ou facteurs sous-jacents expliquent ces relations ?

- Élaborer un réseau de généralisation : cela implique de tirer des conclusions générales à partir des données et des analyses spécifiques. Par exemple, si une certaine relation entre les variables a été observée dans plusieurs systèmes politiques différents, il peut être possible de généraliser cette relation à tous les systèmes politiques.

- Découvrir de nouveaux phénomènes : enfin, l'élaboration d'une théorie politique peut aussi impliquer la découverte de nouveaux phénomènes ou tendances au sein des systèmes politiques. Cela pourrait être le résultat d'une analyse approfondie des données, ou cela pourrait découler de l'application de la théorie à de nouveaux contextes ou situations.

Ces fonctions forment ensemble un cadre pour l'élaboration de théories politiques robustes et utiles. Easton a soutenu que l'application de ce cadre pourrait aider à organiser et à clarifier notre compréhension des systèmes politiques.

La théorie systémique, telle que présentée par David Easton, propose une approche globale pour analyser les systèmes politiques. Elle ne se limite pas à l'étude des institutions politiques ou des comportements individuels, mais cherche plutôt à comprendre les systèmes politiques comme des ensembles interconnectés de structures, de processus et de relations. Les différentes composantes d'un système politique - telles que le gouvernement, les groupes d'intérêt, les citoyens, etc. - sont considérées comme faisant partie d'un même système global. Ces composantes sont interdépendantes et interagissent les unes avec les autres de manière complexe. De plus, la théorie systémique peut également être utilisée pour comparer et classifier les différents types de régimes politiques. Par exemple, on pourrait utiliser cette approche pour distinguer entre les démocraties libérales, les régimes autoritaires, les monarchies constitutionnelles, etc., en fonction de la manière dont leurs différents sous-systèmes sont organisés et interagissent. La théorie systémique offre un cadre analytique puissant pour étudier les systèmes politiques. Elle permet une compréhension plus nuancée et intégrée de la complexité et de la dynamique des systèmes politiques.

Jean-William Lapierre (1921 - 2007)

Jean-William Lapierre était un sociologue et politologue français. Il est connu pour ses travaux sur la théorie politique et la sociologie du pouvoir. Au cours de sa carrière, il a également occupé plusieurs postes universitaires, notamment à l'Université Paris 8 et à l'Institut d'études politiques de Paris.

Lapierre a développé une approche unique de la théorie politique, qu'il a appelée "analyse stratégique". Selon cette approche, le pouvoir est considéré comme un phénomène relationnel et stratégique, qui implique des interactions complexes entre différents acteurs sociaux. Cette perspective s'écarte de certaines approches plus traditionnelles de la théorie politique, qui tendent à concevoir le pouvoir comme une propriété ou une ressource détenue par certains acteurs. Dans ses travaux, Lapierre a également mis l'accent sur l'importance des conflits sociaux et des luttes pour le pouvoir dans la formation et le fonctionnement des sociétés politiques. Il a souligné le rôle de la domination, de la résistance et de la négociation dans ces processus. Lapierre a eu une influence considérable dans le domaine des sciences politiques et sociales, et ses idées continuent d'être discutées et débattues aujourd'hui.

Jean-William Lapierre soutenait que tous les systèmes politiques, quels que soient leur culture ou leur contexte historique, peuvent être analysés en utilisant une approche systémique. Selon lui, tous les systèmes politiques partagent certaines caractéristiques fondamentales et fonctionnent selon des principes communs, malgré leurs différences apparentes. L'approche systémique de Lapierre implique l'observation et l'analyse des relations et interactions entre les différentes parties d'un système politique, ainsi que la manière dont ces parties contribuent à la fonction globale du système. Il a insisté sur le fait que l'analyse systémique doit prendre en compte non seulement les structures et les processus politiques, mais aussi les comportements et les attitudes des acteurs au sein du système. Dans son livre "L'analyse des systèmes politiques", Lapierre a développé cette approche en détail, expliquant comment elle peut être utilisée pour comprendre une variété de phénomènes politiques, y compris le pouvoir, la résistance, la domination, et la négociation. Il a également souligné l'importance de la prise en compte des conflits et des tensions au sein des systèmes politiques, qui jouent un rôle clé dans leur dynamique et leur évolution.

Jean-William Lapierre envisageait les systèmes politiques comme des systèmes de transformation d'informations, une idée centrale dans l'approche systémique. Cette transformation d'informations se déroule en deux étapes principales : l'input (entrée) et l'output (sortie).

- Input : Cette étape concerne le recueil et le traitement des informations et des demandes provenant de la société. Cela peut comprendre les opinions publiques, les demandes des citoyens, les problèmes sociaux, les défis économiques, etc. Ces informations sont recueillies par divers moyens, tels que les sondages d'opinion, les consultations publiques, les protestations, les groupes de pression, etc.

- Output : Cette étape concerne la réponse du système politique aux informations et aux demandes recueillies lors de l'étape de l'input. Cela peut comprendre l'élaboration de nouvelles politiques, la mise en œuvre de programmes, la modification de lois, la prise de décisions judiciaires, etc. L'output est le résultat visible du fonctionnement du système politique.

Selon cette perspective, l'efficacité d'un système politique peut être mesurée par sa capacité à transformer efficacement les inputs en outputs appropriés. C'est-à-dire, sa capacité à répondre efficacement aux demandes et aux besoins de la société. Il est également à noter que les outputs du système politique peuvent à leur tour influencer les inputs, créant ainsi une boucle de rétroaction. Par exemple, une nouvelle politique (output) peut provoquer des réactions de la part du public (input), ce qui peut à son tour influencer l'élaboration de politiques futures.

L'analyse systémique, telle que développée par des chercheurs comme Jean-William Lapierre, peut nous aider à comprendre des événements historiques comme la Révolution française. Dans ce cas, le système politique de la monarchie absolue a été incapable de traiter efficacement les inputs de la société française, en particulier les signaux de mécontentement croissant et de crise économique.

Louis XIV a construit Versailles dans un but politique : centraliser son pouvoir et affirmer son contrôle sur la noblesse. En invitant les nobles à résider à Versailles, il a pu les garder sous sa surveillance, minimisant ainsi leur capacité à comploter ou à se rebeller contre lui. Cependant, en établissant la cour à Versailles, Louis XIV s'est également éloigné de Paris, le centre politique, économique et culturel de la France. Cela pourrait avoir limité sa capacité à comprendre et à répondre efficacement aux problèmes de la population parisienne et, plus largement, du peuple français. Vesrsailles en tant qu'extraterritorialité est une interprétation possible du concept d'input et d'output dans le contexte de l'analyse systémique. L'input pourrait être considéré comme l'information ou les signaux venant de la société, tandis que l'output est la réponse ou l'action du système politique en réponse à ces signaux. Le roi Louis XVI, comme ses prédécesseurs, s'est éloigné des réalités de la vie de ses sujets, en particulier ceux de Paris. En se retirant à Versailles, il a perdu une partie de sa capacité à recevoir et à comprendre les inputs de la société parisienne. Il n'a pas réussi à comprendre et à répondre aux signaux d'agitation sociale croissante et aux problèmes économiques causés par les mauvaises récoltes et les épidémies. Lorsque la crise a atteint son paroxysme, le système politique de la monarchie a été incapable de produire les outputs nécessaires pour résoudre la crise. La réponse inadéquate du roi à la crise, notamment sa résistance aux réformes, a conduit à un mécontentement encore plus grand et finalement à la révolution. Nous pouvons noter ce bref échange entre Louis XVI et La Rochefoucauld : « -monsieur le roi, il s’est passé quelque chose. –c’est une révolte ?, -non sire, c’est une révolution ! »[1]. Cette analyse souligne l'importance pour un système politique de pouvoir traiter efficacement les inputs de la société et de produire des outputs appropriés. Si un système politique ne peut pas le faire, il peut être confronté à une instabilité et à des bouleversements, comme ce fut le cas pendant la Révolution française.

Dans une perspective systémique, la gestion du politique est perçue comme un équilibre dynamique entre les inputs (informations ou ressources entrantes) et les outputs (actions ou décisions politiques). Les inputs sont les informations, demandes ou ressources que le système politique reçoit de l'environnement social, économique et culturel. Ils peuvent inclure des choses comme les opinions publiques, les attentes sociales, les ressources économiques, etc. En revanche, les outputs sont les réponses ou actions du système politique à ces inputs. Ils peuvent inclure des choses comme les politiques publiques, les lois, les règlements, les décisions judiciaires, etc. L'objectif est de créer des outputs qui répondent aux inputs de manière efficace et appropriée. Cependant, si le système politique ne reçoit pas d'inputs adéquats ou s'ils sont mal interprétés, les outputs peuvent ne pas correspondre aux besoins ou aux attentes de la société. Par exemple, si un gouvernement ne reçoit pas d'informations précises sur les besoins de sa population, il peut prendre des décisions qui sont hors de propos ou inadéquates. C'est pourquoi une gestion efficace des inputs et des outputs est cruciale pour le bon fonctionnement d'un système politique.

Jean-William Lapierre a mis en avant le caractère décisionnel du système politique dans son approche systémique. Il considère que le système politique est un système complexe qui doit constamment prendre des décisions et agir en fonction des informations et des ressources qu'il reçoit de son environnement (les inputs). Lapierre souligne également que même si un système politique peut être guidé par des idéologies ou des principes politiques particuliers, il doit toujours tenir compte de la réalité de la situation et adapter ses décisions en conséquence. En d'autres termes, un système politique ne peut pas se permettre de faire abstraction de la réalité sociale, économique et culturelle dans laquelle il opère. Cela signifie que le système politique doit constamment évaluer et réévaluer ses actions et ses décisions (les outputs) en fonction des informations et des ressources qu'il reçoit (les inputs). C'est ce processus d'évaluation et de réévaluation qui permet au système politique de rester adapté à son environnement et de répondre efficacement aux besoins et aux attentes de la société.

La notion de système décisionnel est centrale : un système politique doit prendre des décisions sur la base des informations dont il dispose, aussi incomplètes ou incertaines soient-elles. C'est ce processus de prise de décision qui donne lieu à des outputs, c'est-à-dire des actions, des politiques ou des règles. Mais un système politique n'est pas simplement un automate qui suit un programme prédéfini. Il doit constamment s'adapter et évoluer en réponse à son environnement. Les inputs (informations, ressources, demandes de la société, etc.) sont constamment en flux, et le système politique doit être capable d'ajuster ses outputs en conséquence. Il est également important de noter que cette théorie met en avant l'idée que le politique est une activité qui ne se réduit pas à la seule prise de décision. Il s'agit aussi de gérer les tensions et les conflits, d'arbitrer entre les différents intérêts, de construire du consensus, etc. En ce sens, la théorie systémique du politique offre une vision très dynamique et complexe de ce qu'est l'activité politique.

La vision de Lapierre concernant le système politique est bien celle d'un système d'action qui fonctionne dans un environnement incertain et avec des informations incomplètes. L'accent est mis sur la nécessité de gérer ces incertitudes et de prendre des décisions malgré elles. Dans ce cadre, un système politique doit constamment évaluer et réévaluer les ressources disponibles (qui peuvent être matérielles, humaines, informationnelles, etc.) et les contraintes (qui peuvent être des règles, des normes, des attentes sociales, etc.) qui s'appliquent à lui. Il doit également être capable d'anticiper les conséquences potentielles de ses actions, bien qu'il ne puisse jamais avoir une certitude absolue à ce sujet. Cela implique une capacité à être flexible et adaptable, à apprendre de l'expérience et à ajuster constamment les actions en fonction des retours d'information (ou feedback). C'est une vision du politique qui est à la fois réaliste et dynamique, et qui met en avant l'importance de la gestion de l'incertitude et de l'information dans l'action politique.

L'essence de la gestion politique peut souvent être réduite à la recherche du "moins mal" possible. Les décideurs politiques doivent constamment jongler avec des ressources limitées, des demandes conflictuelles, des incertitudes sur le futur et une multitude d'autres contraintes et défis. Ils doivent donc souvent faire des compromis, parfois difficiles, et choisir parmi des options qui sont toutes loin d'être parfaites. Leur objectif est alors de minimiser les inconvénients et les coûts de ces compromis, tout en maximisant les bénéfices potentiels pour la société. C'est dans ce sens que l'on peut dire qu'ils cherchent à gérer le "moins mal" possible. Cette perspective réaliste sur la gestion politique met en lumière la complexité et la difficulté de prendre des décisions politiques dans un monde incertain et toujours en mouvement.

Les limites de ces deux approches

Limites de l’approche fonctionnaliste

L'approche fonctionnaliste a fait l'objet de nombreuses critiques pour diverses raisons. Voici quelques-unes de ses limites principales :

- Réductionnisme : Le fonctionnalisme peut être accusé de réductionnisme car il tend à voir la société comme une machine bien huilée où chaque pièce a une fonction spécifique. Cette vision peut ignorer la complexité et l'interdépendance des phénomènes sociaux et la possibilité de conflits ou de tensions au sein de la société.

- Incapacité à expliquer le changement social : Le fonctionnalisme est souvent critiqué pour son incapacité à expliquer le changement social. Il est souvent concentré sur l'équilibre et la stabilité de la société, et a du mal à expliquer pourquoi et comment la société change.

- Néglige l'agentivité individuelle : L'approche fonctionnaliste tend à privilégier une vision macroscopique de la société, négligeant souvent l'agentivité des individus. Il peut donc avoir du mal à expliquer comment les individus peuvent influencer la société et comment leurs actions peuvent conduire à des changements sociaux.

- Conservatisme : Le fonctionnalisme a été critiqué pour son conservatisme implicite. En se concentrant sur le maintien de l'équilibre et de la stabilité, il peut sembler justifier l'ordre social existant et résister à l'idée de changement social. Cela peut parfois conduire à une justification implicite des inégalités sociales.

Malgré ces limites, le fonctionnalisme a joué un rôle important dans la sociologie et a apporté de précieuses contributions à notre compréhension de la société. Cependant, il est important de prendre en compte ces critiques lors de l'utilisation de l'approche fonctionnaliste pour analyser la société.

Limites de l’approche systémique

L'approche systémique, bien qu'elle offre de nombreux avantages pour comprendre les organisations et les interactions politiques, présente également certaines limites. Voici quelques-uns de ces défis :

- Sur-simplification : L'approche systémique peut parfois simplifier excessivement les phénomènes sociaux et politiques en les décomposant en systèmes et sous-systèmes. La réalité est souvent beaucoup plus complexe et désordonnée que les modèles systémiques ne le suggèrent.

- Manque de considération pour le contexte : Les systèmes politiques sont profondément ancrés dans des contextes sociaux, culturels et historiques spécifiques. L'approche systémique peut parfois négliger ces contextes en se concentrant sur l'analyse des inputs et des outputs du système.

- Comparabilité : L'approche systémique peut donner l'impression que tous les systèmes politiques sont comparables. Cela peut conduire à des généralisations trompeuses et à des jugements de valeur inappropriés.

- Négligence des dynamiques de pouvoir : En se concentrant sur les processus systémiques, cette approche peut négliger les dynamiques de pouvoir, d'inégalité et de conflit qui sont souvent au cœur des systèmes politiques.

- Difficulté à gérer le changement : L'approche systémique peut avoir du mal à expliquer comment les systèmes politiques changent et évoluent au fil du temps. Elle est généralement plus efficace pour analyser l'état actuel des systèmes politiques que pour prévoir ou expliquer le changement.

Ces limites ne signifient pas que l'approche systémique est sans valeur, mais elles suggèrent que les chercheurs doivent l'utiliser avec précaution et en combinaison avec d'autres approches pour obtenir une compréhension plus complète des phénomènes politiques.

Annexes

- Œuvres en ligne de Malinowski sur le site des « Classiques des Sciences sociales »

References

- ↑ Guy Chaussinand-Nogaret, La Bastille est prise, Paris, Éditions Complexe, 1988, p. 102.